“No house can be conceived more warm and cosy than that built of cob, especially when thatched.”

— A Book of The West, Sabine Baring-Gould, 1899

— A Book of The West, Sabine Baring-Gould, 1899

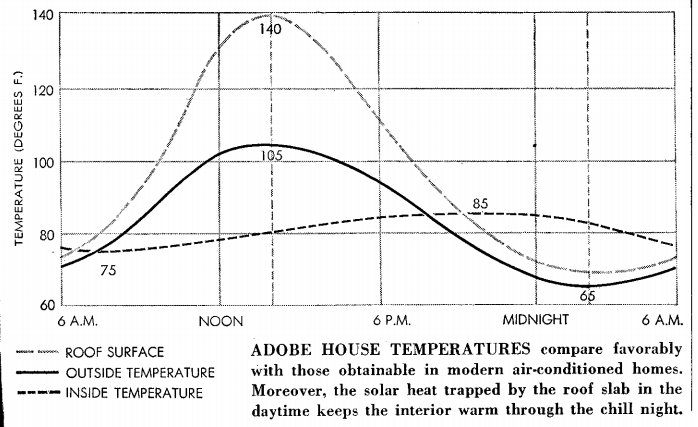

“Cob walls for garden fruit are incomparable. They retain the warmth of the sun and give it out through the night, and when protected on top by slates, tiles, or thatch, will last for centuries.” — A Book of The West, Sabine Baring-Gould, 1899

“Walls of mud, or of compressed earth, are still more economical than those of timber, and if they were raised on brick or stone foundations...their durability would be equal to that of marble, if properly constructed and kept perfectly dry.” — An Old Authority, 1833

You can find suitable soil for cob almost anywhere on Earth, except in places where you have chalk almost at the surface (either soft or hard), as in parts of the U.S., Germany, France, Denmark, The Netherlands, Syria, Egypt, and of course, England: the chalk country above all!

When life gives you chalk: build with "chalk cob". Just exchange soil for soft chalk reasonably crushed, and make sure it does not get wet, because it is possibly the most water sensitive of all building material, but well built it will give you exceptionally strong walls.

If you have hard chalk on your land you can cut it into bricks and use as is (not water sensitive). Exceptionally good. If you live near a chalk quarry you can build an entire house in these, at a fraction of the cost of concrete or fired clay bricks.

Chalk was (and is still!) commonly used for flooring of cow sheds and stables: it absorbs the animal urine, keeping the floor and bedding drier, healthier. Very hygienic. It also costs almost nothing compared to a concrete floor and it is carbon neutral, unlike concrete.

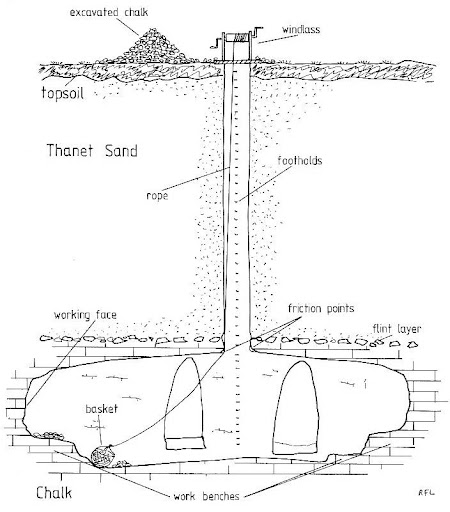

Our ancestors used chalk to make acidic soil neutral and better for agriculture. We still do this today. As a bonus, the chalk mines would make for excellent wells, underground cisterns, cellars. Many of these still remain in England where they are called "deneholes".

"But what about cob in wet climates?" In the old days builders would start with stitching together a thatch coat or covering that would eminently protect the unfinished cob walls from rain for weeks if necessary. Like the thatched roofs of hay ricks. There were even machines.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh