We identified a broadly neutralizing sarbecovirus antibody (S2K146) in collaboration with Matteo Samuele Pizzuto & @DavideCorti6

Work led by @YoungjunPark11 Anna De Marco @tylernstarr @JZhuoming

1/7

biorxiv.org/content/10.110…

Work led by @YoungjunPark11 Anna De Marco @tylernstarr @JZhuoming

1/7

biorxiv.org/content/10.110…

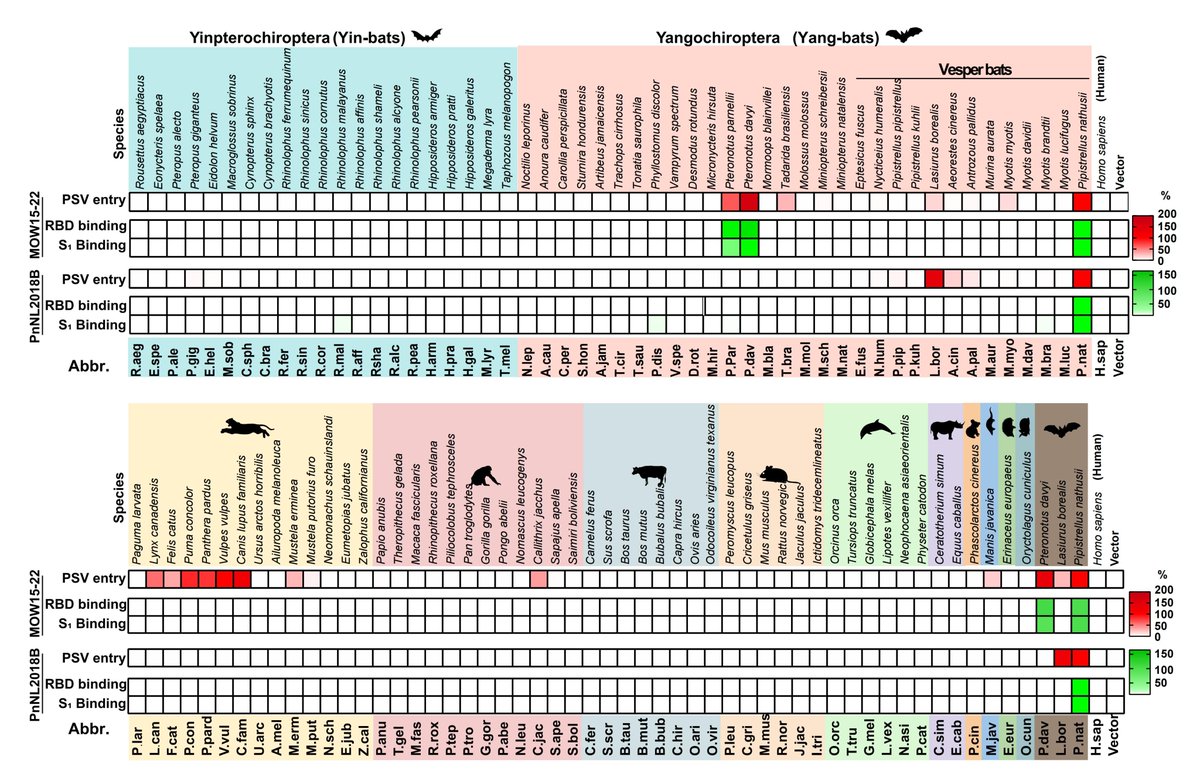

S2K146 binds and broadly neutralizes several SARS-CoV-1-like and SARS-CoV-2-like viruses (clades 1a/1b). It inhibits BtKY72 (clade 3) K493Y/T498W S pseudovirus, as we previously showed that these 2 mutations enable this bat virus to use hACE2.

biorxiv.org/content/10.110…

2/7

biorxiv.org/content/10.110…

2/7

Our #cryoEM structure reveals that S2K146 'mimics' ACE2, as 75% of the residues participating in the epitope are also part of the ACE2 binding site, and is therefore not affected by known variants.

3/7

3/7

Although the receptor-binding motif is highly divergent among sarbecoviruses, neutralization of SARS-CoV-1 is explained by the conservation of many epitope residues with SARS-CoV-2, consistent with the ability of each of these RBDs to bind hACE2.

4/7

4/7

S2K146-mediated neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 is exceedingly difficult to escape, due to severe dampening of ACE2 binding, and the single escape mutant isolated (Y489H) had markedly reduced fitness.

5/7

5/7

S2K146 inhibits ACE2 attachment competitively, triggers S1 shedding and premature spike refolding to the postfusion state and protects hamsters against #SARSCoV2 beta (B.1.351) challenge in a stringent therapeutic (post-exposure) setting.

6/7

6/7

Thank you so much to @coronalexington @SamK_Zepeda @johnbowenbio Kaiti Sprouse Anshu Joshi and our wonderful collaborators including @jbloom_lab @vsv512 @neyts_johan @FLempp and many others not on twitter!

7/7

7/7

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh