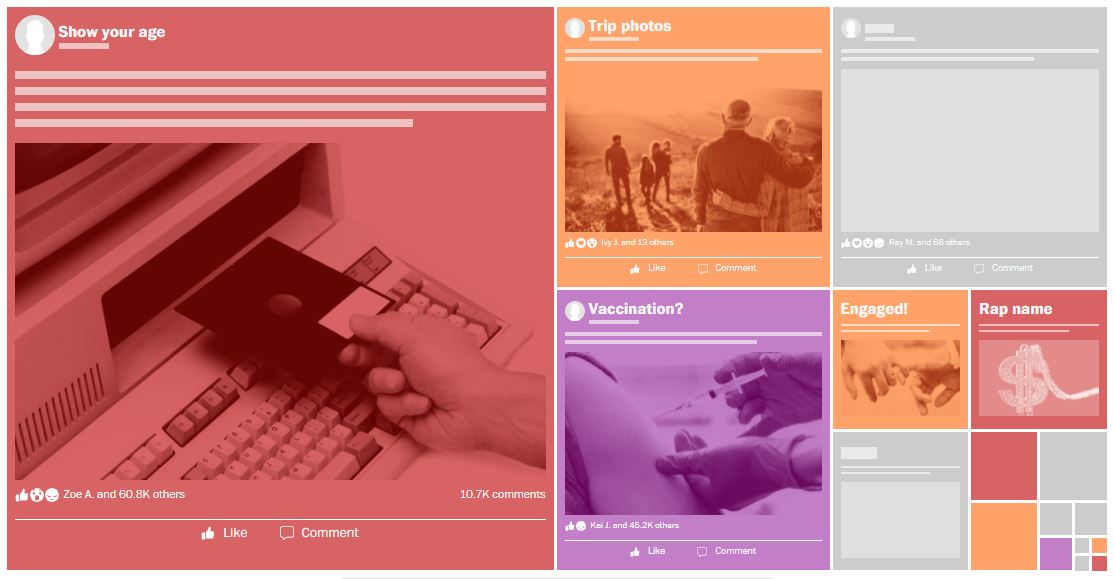

Starting in 2017, Facebook’s ranking algorithm treated emoji reactions as five times more valuable than “likes,” internal documents reveal.

The theory was simple: Posts that prompted lots of reaction emoji tended to keep users more engaged. wapo.st/3GniSCx

The theory was simple: Posts that prompted lots of reaction emoji tended to keep users more engaged. wapo.st/3GniSCx

Facebook’s own researchers were quick to suspect a critical flaw.

Favoring “controversial” posts could open “the door to more spam/abuse/clickbait inadvertently,” a staffer, whose name was redacted, wrote in one of the internal documents. wapo.st/3GniSCx

Favoring “controversial” posts could open “the door to more spam/abuse/clickbait inadvertently,” a staffer, whose name was redacted, wrote in one of the internal documents. wapo.st/3GniSCx

The company’s data scientists confirmed that posts that sparked angry reaction emoji were disproportionately likely to include misinformation, toxicity, and low-quality news.

For three years, Facebook had given special significance to the angry emoji. wapo.st/3GniSCx

For three years, Facebook had given special significance to the angry emoji. wapo.st/3GniSCx

That means Facebook for years systematically amped up some of the worst of its platform, making it more prominent in users’ feeds and spreading it to a much wider audience. wapo.st/3GniSCx

In several cases, documents show Facebook employees on its “integrity” teams raising flags about the human costs of specific elements of the ranking system — warnings that executives sometimes heeded and other times seemingly brushed aside. wapo.st/3GniSCx

The weight of the angry reaction is just one of many levers that Facebook engineers manipulate to shape the flow of information and conversation — one that has been shown to influence everything from users’ emotions to political campaigns to atrocities. wapo.st/3GniSCx

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh