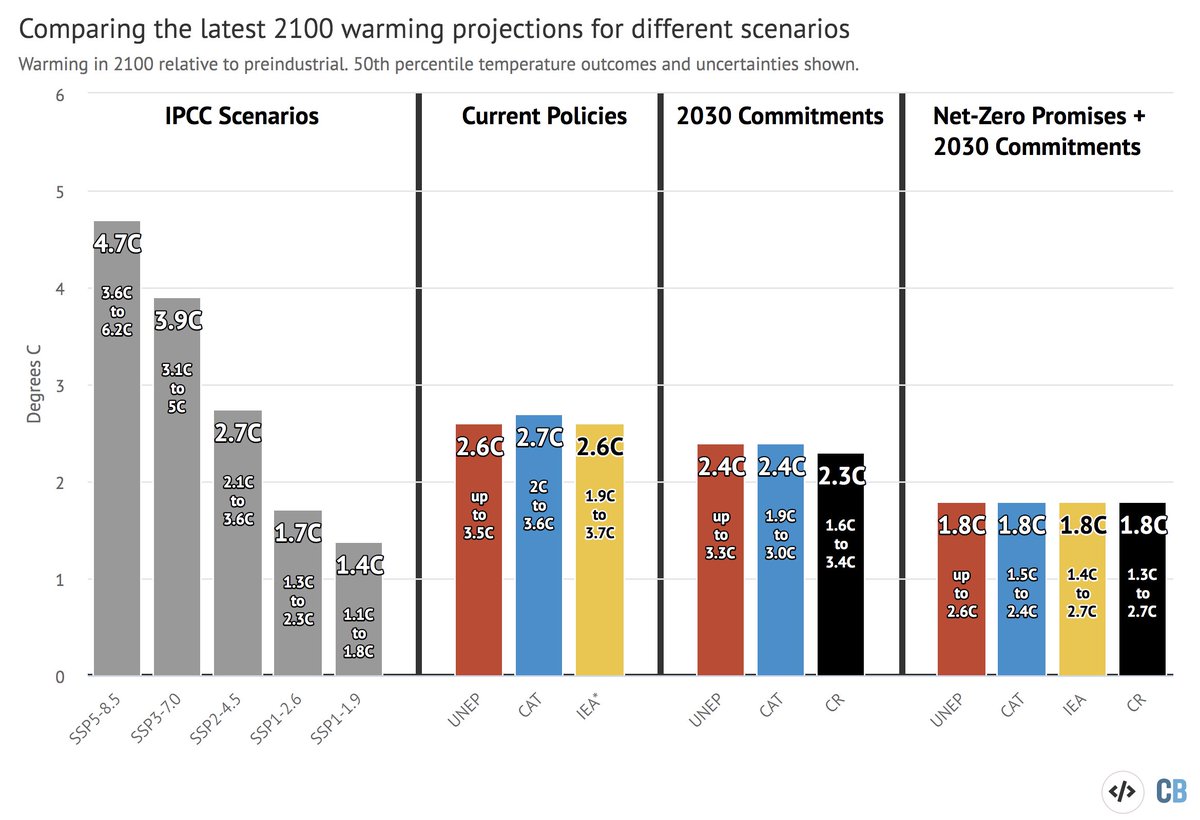

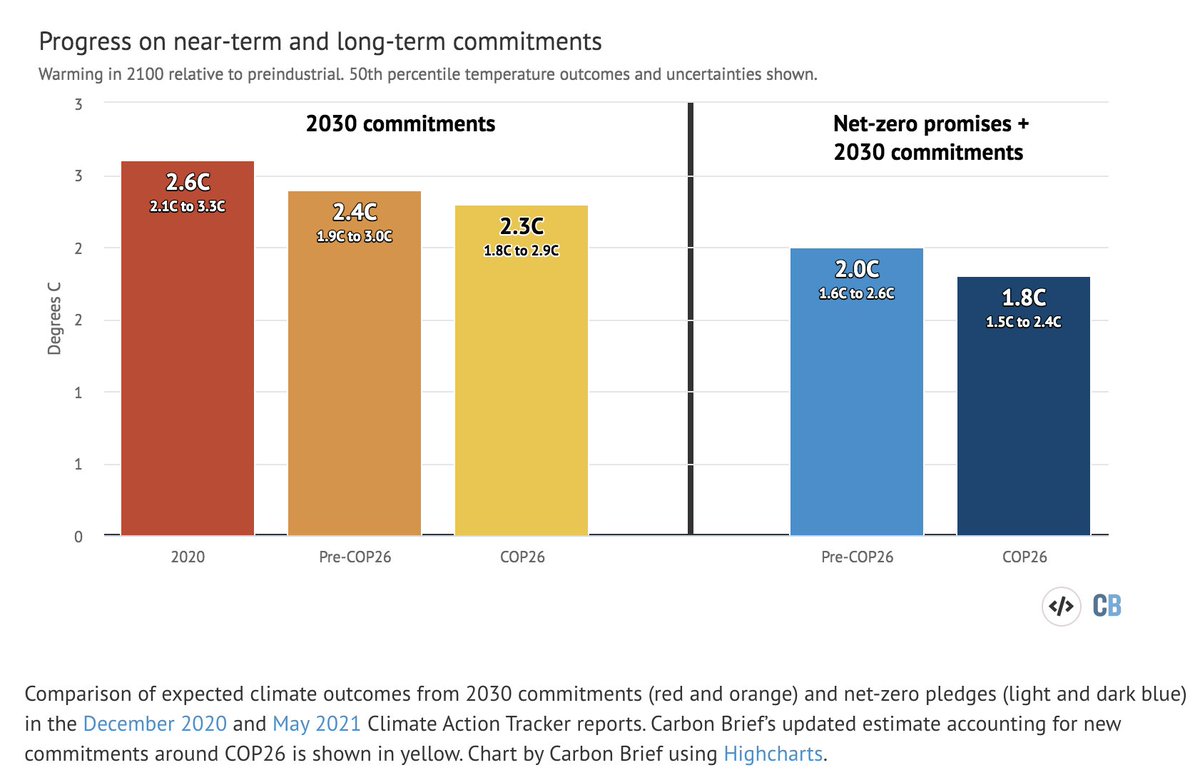

As COP26 comes to a close, its clear it will not put us on a path to 1.5C by itself. It does not ensure we remain below 2C, given gap between long-term ambition and near-term 2030 commitments.

But it does move the needle forward, and tee up another round of stronger commitments.

But it does move the needle forward, and tee up another round of stronger commitments.

If folks were hoping for a dramatic breakthrough, this is not it. But nevertheless it is slow and steady progress towards a lower warming future, even if pace of action means that we may not avoid as much warming as we'd like.

At the end of the day every 0.1C still matters.

At the end of the day every 0.1C still matters.

It also makes real progress on a lot of thorny issues that have bedeviled past negotiations, even though many outstanding issues still remain:

https://twitter.com/James_BG/status/1459593334624817161

The draft final document is here, which will be the agreement barring any last-minute surprises. But its not final until the gavel drops and everyone heads home: unfccc.int/sites/default/…

For more details on climate implications of COP26 outcomes, see: carbonbrief.org/analysis-do-co…

(looks like the language of the final draft will be changed from "phase out" coal to "phase down" coal due to pressure from China and India. This is disappointing, but given the lack of a timeframe for either its unclear it will actually impact future NDCs and domestic policy)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh