Did vaccination drive the evolution of variant (Alpha, Beta, etc...) SARS-CoV-2 viruses? This is a legitimate scientific question, but after looking into it I don't believe this to be the case. 1/19

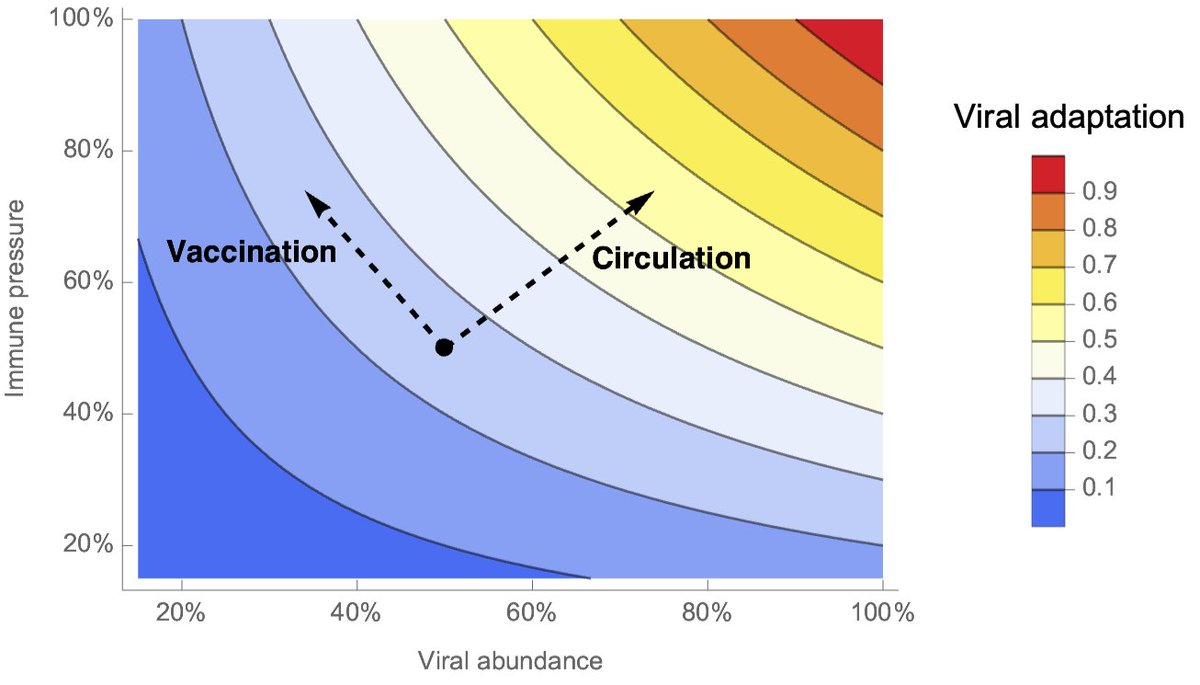

Grenfell et al. 2004 (science.org/doi/10.1126/sc…) lays out the conceptual foundations for thinking about this problem. This figure is a bit hard to parse, but basically vaccination will increase population immunity and move rightward on the x-axis. 2/19

This will increase the strength of selection for immune escape (blue line), but will decrease viral abundance (red line). The rate of viral adaptation (black line) depends on both selection and abundance and so is maximized at an intermediate level of population immunity. 3/19

I've redrawn this concept here. We have viral abundance on the x-axis in arbitrary units of 0% to 100% and population immune pressure on the y-axis also in arbitrary units. Viral adaptation is plotted by color and is just abundance × immune pressure. 4/19

If we start from an intermediate level of viral abundance and population immunity and allow virus to spread further, we'll see increasing viral abundance as well as a wake of immunity in the population. We expect the combination to drive viral adaptation. 5/19

On the other hand, if we vaccinate, we'll see increasing population immunity, but decreasing viral abundance. This suggests more of a wash in terms of viral adaptation, so that adaptation rate is lower in the vaccination scenario than in the circulation scenario. 6/19

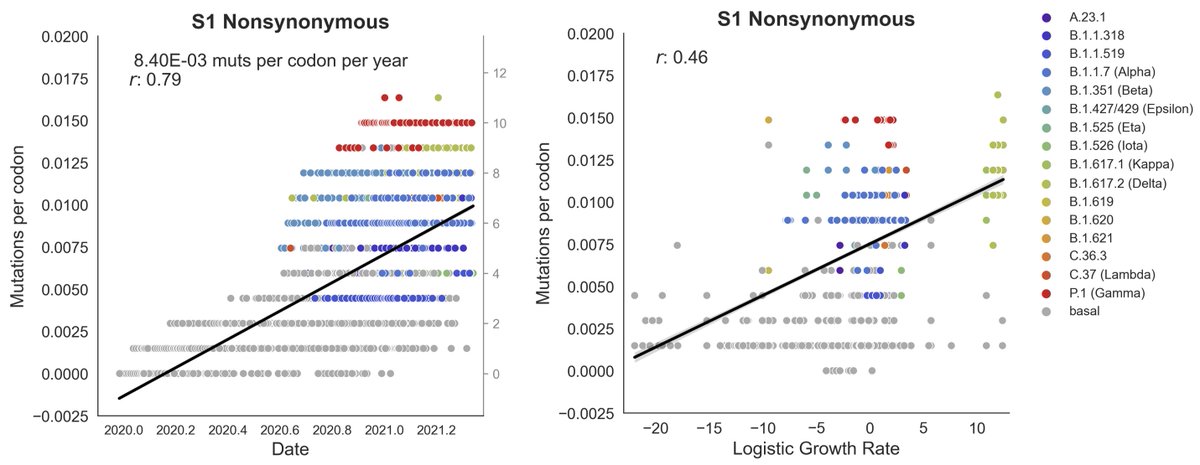

This is all theory. What have we actually observed with SARS-CoV-2? We've seen the highest rates of adaptation in the S1 domain of the spike protein (

https://twitter.com/trvrb/status/1437519281760079873), consistent with effective antibodies from vaccination and infection both targeting S1. 7/19

We also know that S1 is responsible for binding to host cells and so evolution for better binding and replication is also likely to focus on S1 (

https://twitter.com/trvrb/status/1349774308202094594). Host adaptation regardless of immunity may focus on S1. 8/19

So, S1 as target of evolution does not address vaccine-driven evolution. However, we can look at broader correlates in terms of time and place of variant emergence. 9/19

Variant viruses largely evolved during 2020 before widespread vaccination (

https://twitter.com/trvrb/status/1460275919663206401) with the common ancestor of Delta viruses (for example) emerging in ~Oct 2020. 10/19

We also see some specific locations of emergence to be correlated with circulation in 2020 and high seroprevalence (Gamma in Manaus particularly hard hit within Brazil science.org/doi/10.1126/sc…, Iota in NYC particularly hard hit within the US nature.com/articles/s4158…, etc...). 11/19

To this end, @KateKistler revised analysis from bedford.io/papers/kistler… to reconstruct a tree of 20k SARS-CoV-2 genomes, infer date and country of internal nodes and use these inferences to estimate vaccination coverage at internal nodes in the tree from @OurWorldInData. 12/19

If we then compare S1 mutations on phylogeny branches to inferred vaccine coverage we get the following result where branches with mutations at S1 do not correlate with higher inferred vaccine coverage. 13/19

Average vaccine coverage is 7.4% for branches without S1 mutations and 7.0% for branches with S1 mutations (p = 0.71 by Mann-Whitney U test). 14/19

I'd consider this analysis to preliminary, but based on this result alongside general time and place of variant emergence, I think it's safe to conclude there is little evidence for vaccination driving emergence of variant viruses. 15/19

Separately to looking at the evolution of variant viruses, we can see if vaccination is driving their spread. Here, @marlinfiggins has estimated variant-specific Rt through time and across states in the US (

https://twitter.com/trvrb/status/1447566575125495809). 16/19

If we compare variant-specific Rt against vaccine coverage across states and across time we can estimate the reduction in Rt due to vaccination. Doing so, we find that vaccine coverage reduces Rt of non-variant viruses and variant viruses to an equivalent degree. 17/19

This suggests that vaccination in 2021 did not drive spread of variants in the US (in fact it shows that vaccination significantly reduced circulation). This is consistent with variant viruses having spread through increased transmissibility rather than antigenic drift. 18/19

I believe it's unlikely that vaccination drove emergence or spread of variant viruses. In general, we need to get to endemicity through immunity and we can get there by infection or vaccination. Infection gives more opportunity for the virus to transmit and further evolve. 19/19

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh