Time for a pulp countdown now, and today I attempt the impossible by picking my top 10 Ed Emshwiller illustrations!

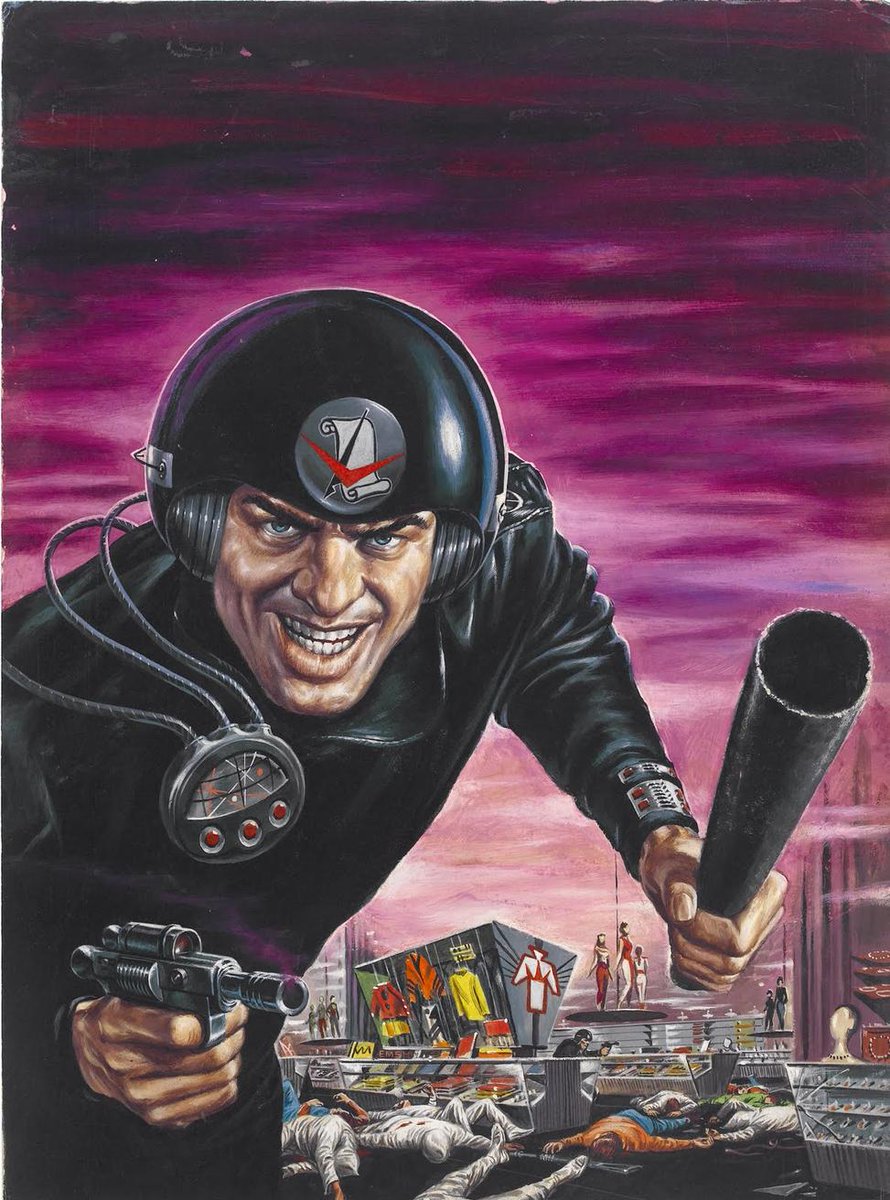

No 10: Crisis in 2140, by H. Beam Piper and John J. McGuire. Ace Doubles, 1957. Emsh paints fantastic villains, and this one is my favourite.

No 9: Ed Emshwiller's alternative cover for Super-Science Fiction, June 1957. The composition is lovely and the spaceship is excellent.

No 8: an interior illustration by Emsh for 'The Visitor at the Zoo' from Galaxy Magazine, April 1963. I just really like these aliens.

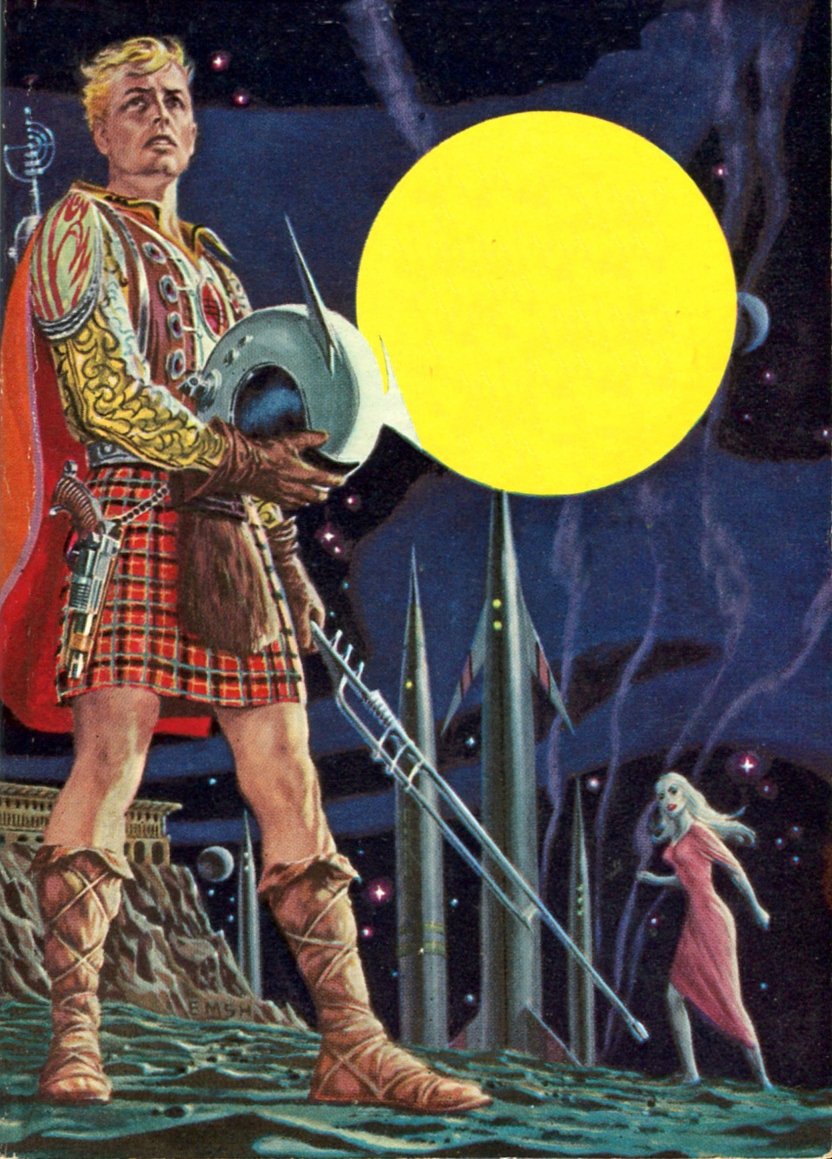

No 7: Star Wars, by Poul Anderson. Ace Doubles, 1957. It's easy to miss the details on this cover, but if anyone can get away with drawing a space kilt Ed Emshwiller can.

No 6: Galaxy Science Fiction, June 1951. There's a lot of wit in Emsh's work and this is one of my favourite Galaxy covers.

No 5: Ed Emshwiller's cover illustration for Rat in the Skull, by Rog Phillips. If Science Fiction, December 1958. Creepy and funny at the same time.

No 4: Starship Soldier, by Robert A. Heinlein. The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, November 1959. Emsh did a lot of Heinlein magazine covers and this captures the essence of what would become Starship Troopers.

No 2: Galaxy Science Fiction, December 1951. Emsh regularly painted the Christmas Galaxy cover, and this one has a great Mid-Mod feel to it.

And No 1: Women's Work, by Murray Leinster. The Original Science Fiction Stories, November 1956. It's just my favourite.

More pulp countdowns another time...

More pulp countdowns another time...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh