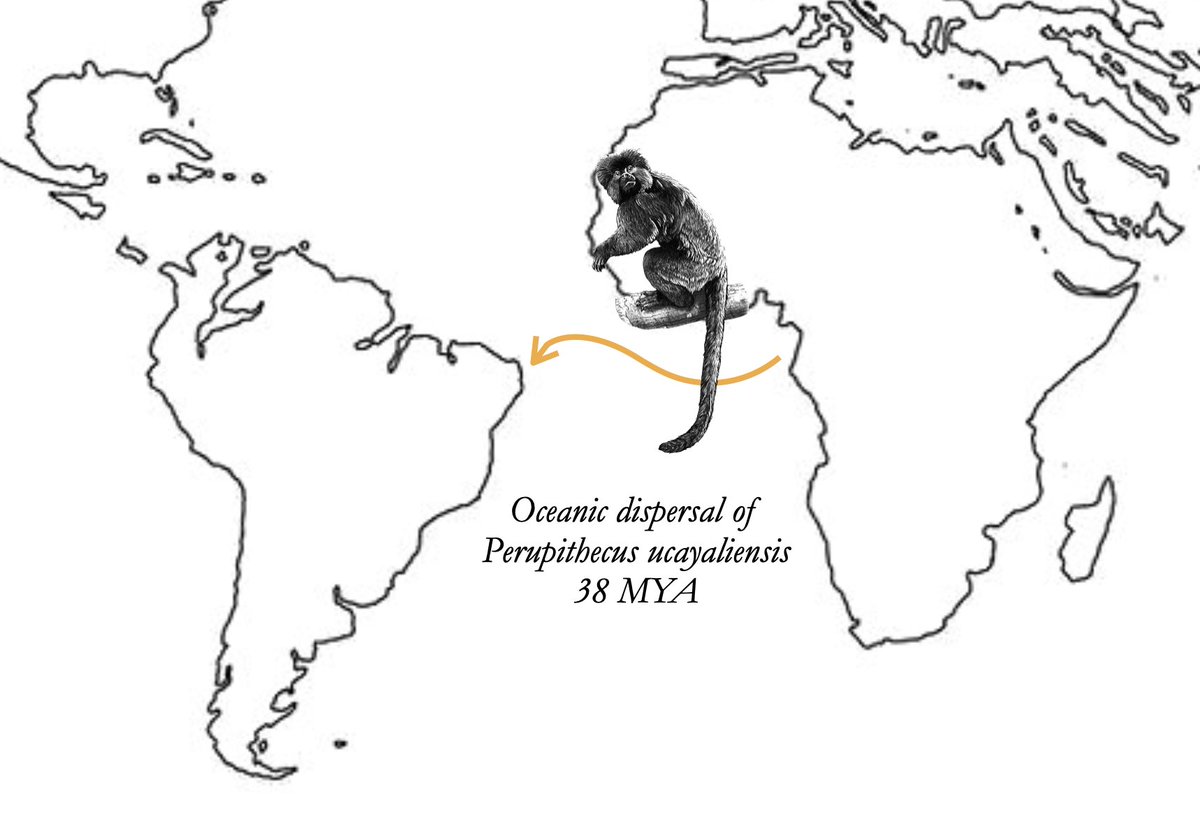

Ever wonder how monkeys ended up in the Americas? Did they cross over land bridges like we did?

The answer is no. They did something even wilder: they floated across the Atlantic (!) millions of years ago. Yes, really.

Let’s talk about oceanic dispersal! (1/5)

The answer is no. They did something even wilder: they floated across the Atlantic (!) millions of years ago. Yes, really.

Let’s talk about oceanic dispersal! (1/5)

So, how did the monkeys pull this off? Well, what happened is called a "rafting event": a piece of earth breaks off, with its flora & fauna intact, & essentially turns into a small floating island. In the Oligocene, the continents were closer, so the journey was shorter. (2/5)

As unlikely as it seems, according to genetic evidence, this type of event happened several times! Monkeys seem to have also rafted to the Caribbean (~11-15MYA), & the lemurs of Madagascar floated across the Mozambique Channel (~50-60MYA), among other rafting events. (3/5)

Of course, monkeys aren't the only animals who disperse via oceanic routes. There's also good evidence that critters like rodents, lizards, spiders, and iguanas were on rafts, too, and made it out to Madagascar, South America, and Australia. (4/5)

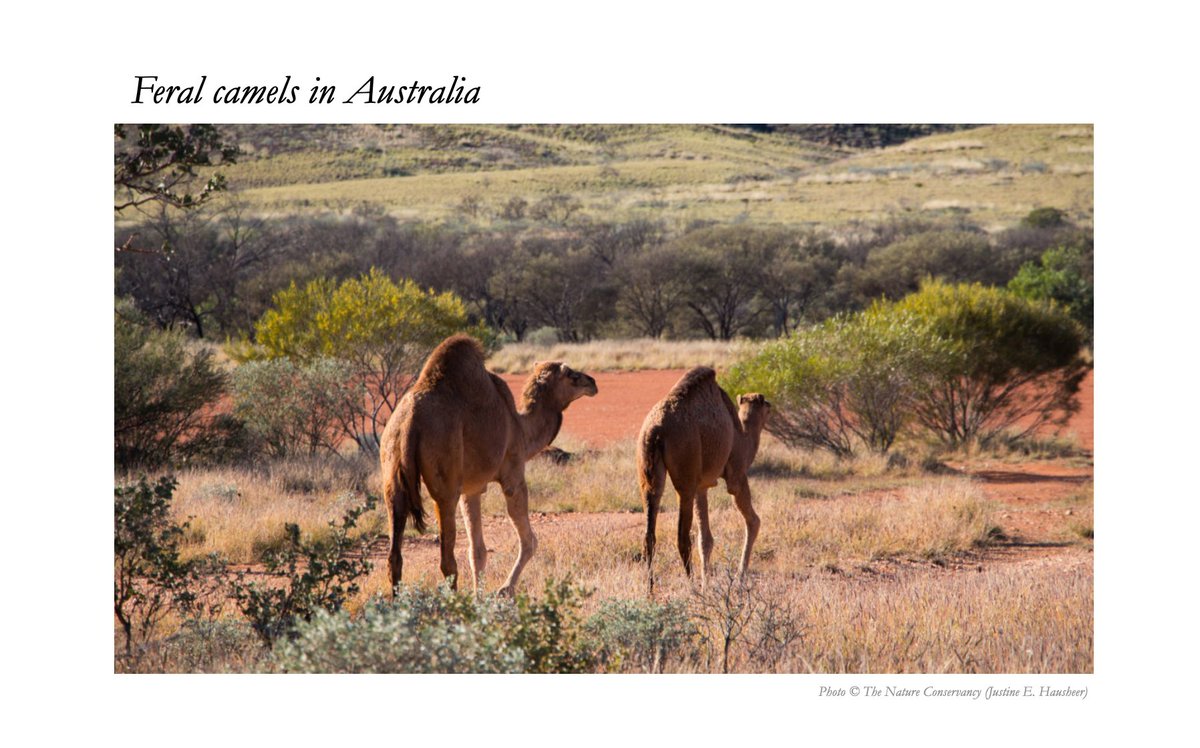

In more recent history, instead of floating islands, animals have dispersed by tagging along with humans on their ships (& frequently wreaking havoc on native ecosystems). This is how we ended up with a quarter million feral camels in Australia! 🐪 (5/5)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh