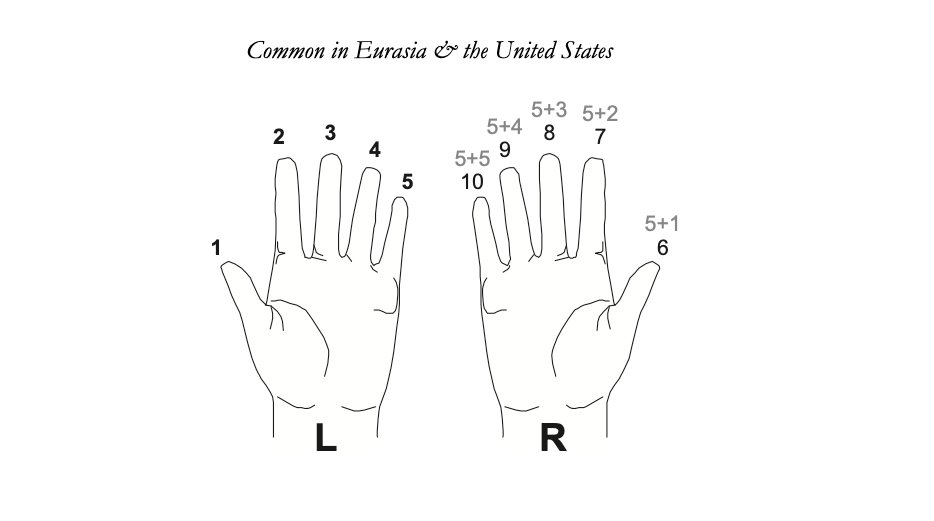

Humans have long needed a way to keep track of numbers as they count. In many cultures, finger counting is common. If you live in the United States or China, you probably count to five like this, but there are many different ways to achieve the same goal. (1/8)

Variations of five-finger counting exist all around the globe, and between languages, as well. The Pekai-Alue in Papua New Guinea are notable in that the folded, rather than the extended, fingers are the ones counted. (2/8)

What happens when you need to count past five? Well, then it gets more interesting. In the US and much of Eurasia, the counting continues onto the other hand, up to 10. If you need to go past that, you often just repeat the cycle from the beginning. (3/8)

But other cultures have made clever use of other body parts for counting, such as toes and knuckles. Others, such as the Oksapmin counting system, work their way around 27 body parts. (4/8)

And actually, why limit yourself to just integers? The Romans used their fingers to keep track of numbers up to three decimal points, and old Chinese had a way of tracking up to four. (5/8)

These are all body-based representations of numbers, but humans also have lots of other counting aids, like tallies. You may be familiar with this system, which tallies with vertical lines up to four, then strikes across to represent five. (6/8)

But other systems for tallying exist, like the one below which sequentially forms the Chinese character 正 (pronounced zhèng, meaning "true" or "correct"), or the one further down that completes a little box with a line through it. (7/8)

This is just a sample of how counting systems vary, but should give you a little insight into the fun & clever counting aids that have culturally evolved. For more, check out the Bender & Beller paper below (where most of the figures are from!) (8/8) sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh