One month ago, I wrote a first thread on #omicron (before it was called that) and I said we needed patience and we would learn a lot more.

So where are we today?

A quick #omicron thread before I sign off for a few days:

So where are we today?

A quick #omicron thread before I sign off for a few days:

https://twitter.com/kakape/status/1464226057045876754?s=21

WHAT WE HAVE LEARNED:

A lot of the early fears have been borne out.

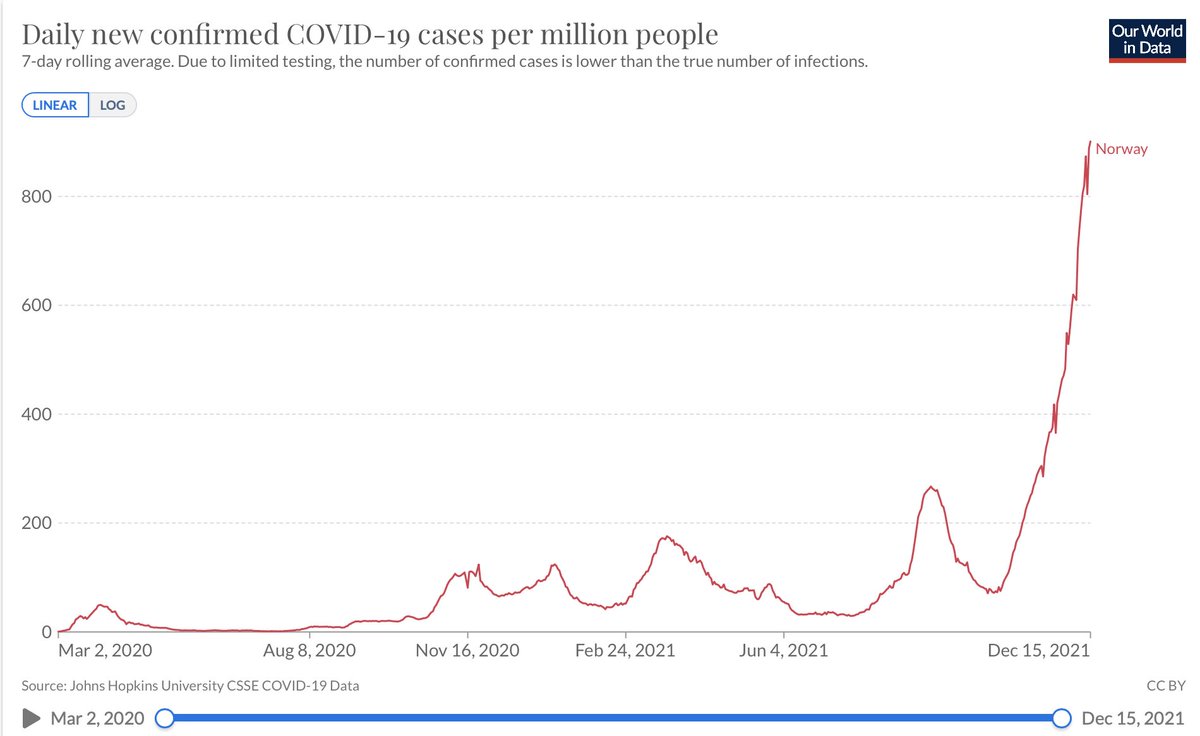

The virus is spreading in many countries just as it did in SAfrica.

It clearly has a huge growth advantage over Delta.

It is a lot better at infecting vaccinated and recovered individuals than previous variants.

A lot of the early fears have been borne out.

The virus is spreading in many countries just as it did in SAfrica.

It clearly has a huge growth advantage over Delta.

It is a lot better at infecting vaccinated and recovered individuals than previous variants.

BUT:

As the virus has spread, we have seen some hopeful signs as well.

We have seen fewer hospitalisations so far than in previous waves.

We have seen a faster than expected turnaround in South Africa.

We have early data suggesting the virus *might* be inherently milder.

As the virus has spread, we have seen some hopeful signs as well.

We have seen fewer hospitalisations so far than in previous waves.

We have seen a faster than expected turnaround in South Africa.

We have early data suggesting the virus *might* be inherently milder.

WHAT WE HAVE YET TO LEARN:

It is still unclear how much of the lower number of severe cases in this wave is down to the virus itself having changed to cause milder disease and how much is down to it being able to infect people protected from severe disease.

It is still unclear how much of the lower number of severe cases in this wave is down to the virus itself having changed to cause milder disease and how much is down to it being able to infect people protected from severe disease.

(If you take the Imperial College report, you can see that a lot depends on your assumptions about how many of the infected people now had prior infections.

If a lot of the mild infections are actually in recovered people then it is more about immunity and less about the virus. )

If a lot of the mild infections are actually in recovered people then it is more about immunity and less about the virus. )

Given data so far and first indications of plausible mechanisms from lab experiments, I would say that both factors probably play a role.

But as UK's latest threat assessment says: "We cannot confidently quantify the relative contributions of these 2 factors at present.”

But as UK's latest threat assessment says: "We cannot confidently quantify the relative contributions of these 2 factors at present.”

Why is it important?

Because it will partly decide how #omicron plays out in countries with lower population immunity than South Africa or UK.

Because it will partly decide how #omicron plays out in countries with lower population immunity than South Africa or UK.

The other important and interesting question raised by the South African wave and some of the early lab data is about generation time:

Do cases in an infection chain follow one another faster than they did with previous variants?

Do cases in an infection chain follow one another faster than they did with previous variants?

That is important because the overall size of a wave really depends on the transmissibility of the virus. The generation time mostly decides how fast these cases accrue.

So a shorter generation time could lead to a shorter, narrower wave, as seen in South Africa.

So a shorter generation time could lead to a shorter, narrower wave, as seen in South Africa.

As the latest #omicron assessment from @WHO notes:

“At the tie [sic] of writing, estimates of generation times for Omicron are still needed to better understand the observed dynamics.”

who.int/docs/default-s…

“At the tie [sic] of writing, estimates of generation times for Omicron are still needed to better understand the observed dynamics.”

who.int/docs/default-s…

@WHO WHAT DOES IT ALL MEAN?

Omicron clearly has the potential to cause a lot of disease in a short time.

That will add to the burden of healthcare systems already strained (for instance in Germany), both with severe cases needing treatment and mild cases leading to staff shortage.

Omicron clearly has the potential to cause a lot of disease in a short time.

That will add to the burden of healthcare systems already strained (for instance in Germany), both with severe cases needing treatment and mild cases leading to staff shortage.

@WHO How it will play out in different countries will depend a lot on the answers to the open questions I outlined (and others, like how omicron affects children, the risk of long covid, etc.)

So message is still:

The next few weeks will be dangerous and difficult.

So message is still:

The next few weeks will be dangerous and difficult.

@WHO But overall, things could have looked bleaker at this point.

(There have been other good news: paxlovid, Novavax)

The biggest threat to all our health and wellbeing is still our utter failure at making the tools to fight #covid19 available to the most vulnerable everywhere.

(There have been other good news: paxlovid, Novavax)

The biggest threat to all our health and wellbeing is still our utter failure at making the tools to fight #covid19 available to the most vulnerable everywhere.

@WHO I was hoping the world would be in a different situation as 2021 ends, but we are where we are.

It’s worth reflecting on how/why we have not used #covid19 vaccines to their full potential this year. I tried to do that in this piece:

science.org/content/articl…

It’s worth reflecting on how/why we have not used #covid19 vaccines to their full potential this year. I tried to do that in this piece:

science.org/content/articl…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh