Ninety seven years ago, #OTD in 1925, Edwin Hubble announced that our Milky Way was just one of many lonely little islands of stars sprinkled throughout the Universe. Andromeda and all the other “spiral nebulae” were in fact separate galaxies, outside the Milky Way.

Hubble’s announcement — other galaxies exist! — was made on the third day of the 33rd Meeting of the American Astronomical Society, in a paper read by H.N. Russell. The meeting started on December 30th; I don’t know if Hubble waited for New Year’s Day to be dramatic.

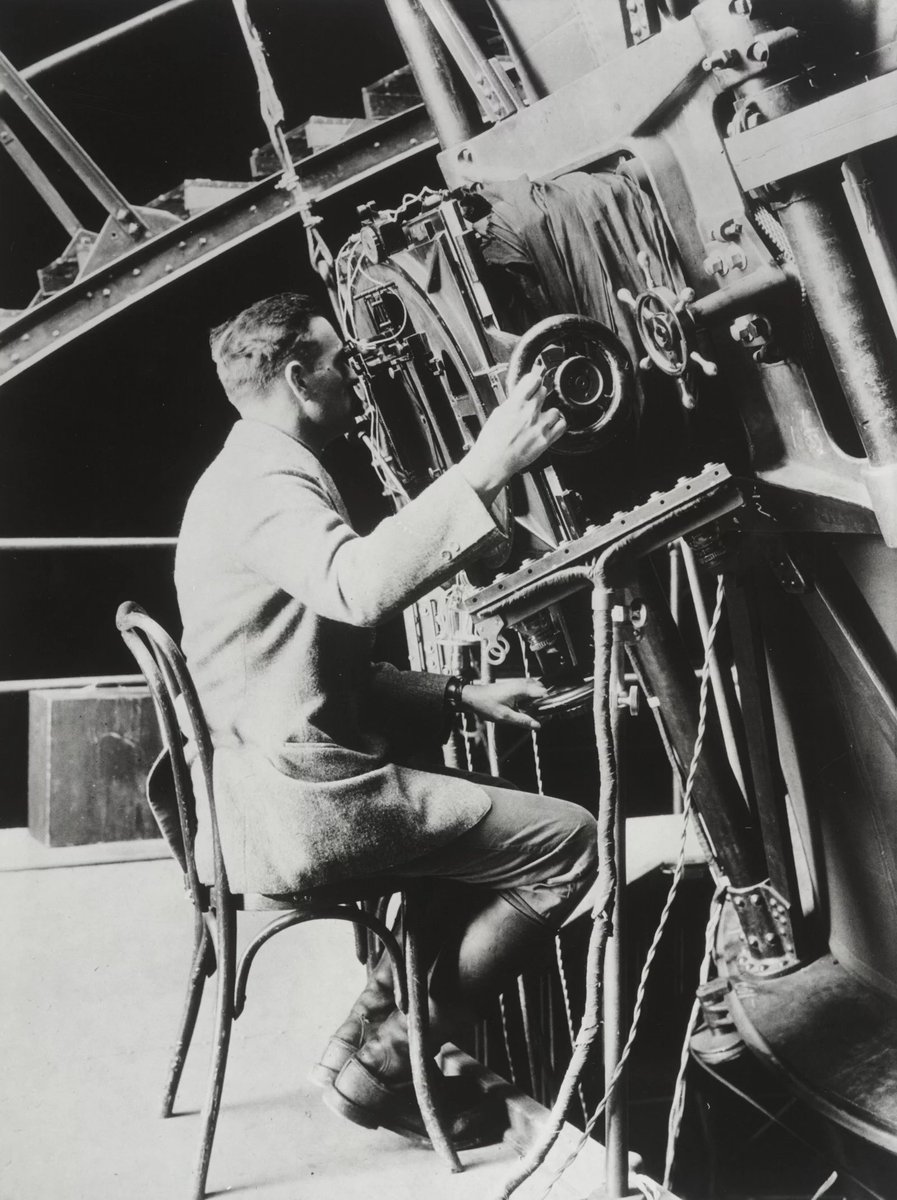

Hubble’s work, conducted with the 100-inch Hooker Telescope at Mount Wilson observatory, relied on earlier measurements by Vesto Slipher and Henrietta Swan Leavitt’s results on Cepheid variable stars.

Image: Huntington Library

Image: Huntington Library

It’s hard to imagine the pre-Hubble view of the Universe, though it was less than 100 years ago. Many (if not most) astronomers believed that the collection of stars we now recognize as our galaxy was… everything.

But there had always been astronomers who suspected that the Milky Way was just one of many galaxies. This view goes at least as far back as Immanuel Kant’s “Universal Natural History and Theory of the Heavens,” which he published anonymously in 1755.

The astronomer Harlow Shapley was perhaps the leading proponent of the establishment view at the time of Hubble’s announcement. He had long argued that spiral nebulae seen by astronomers — shapes any kid would now recognize as galaxies — were dust clouds inside the Milky Way.

Hubble kept Shapley in the loop as he built his case for separate galaxies, alerting him to the discovery of Cepheid variables in M31, M33, and other spiral nebulae throughout 1924.

It was the identification of Cepheid variables that allowed Hubble to prove that M31 and other spiral nebulae were so far away that they must be outside the Milky Way.

A Cepheid variable is a type of star whose brightness waxes and wanes over a period of time that tightly correlates with its maximum brightness. If you measure that period then you know its absolute brightness. Then if you know how bright it appears you can estimate its distance.

This important relationship, one of our primary tools in establishing the scale of the Universe, was first laid out by astronomer Henrietta Swan Leavitt:

https://twitter.com/mcnees/status/1411705344405999617

Anyway, Shapley doubted Hubble’s claims at first, but eventually relented in the face of growing evidence.

Upon receiving one of Hubble's letters, Shapley remarked to doctoral student Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin “Here is the letter that destroyed my universe.”

Upon receiving one of Hubble's letters, Shapley remarked to doctoral student Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin “Here is the letter that destroyed my universe.”

It seems hard to believe, but there are people alive today who were born into what scientists thought was a much smaller universe.

Alas, I had been planning on using Betty White here. She was born almost three years before Hubble’s announcement.

Alas, I had been planning on using Betty White here. She was born almost three years before Hubble’s announcement.

Astronomically speaking, January 1st is a meaningless date. However, today is also the 97th anniversary of humanity taking a monumental step towards understanding our place in a Universe that is vast and puzzling, but ultimately knowable.

Happy New Year!

Image: Richard Powell

Happy New Year!

Image: Richard Powell

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh