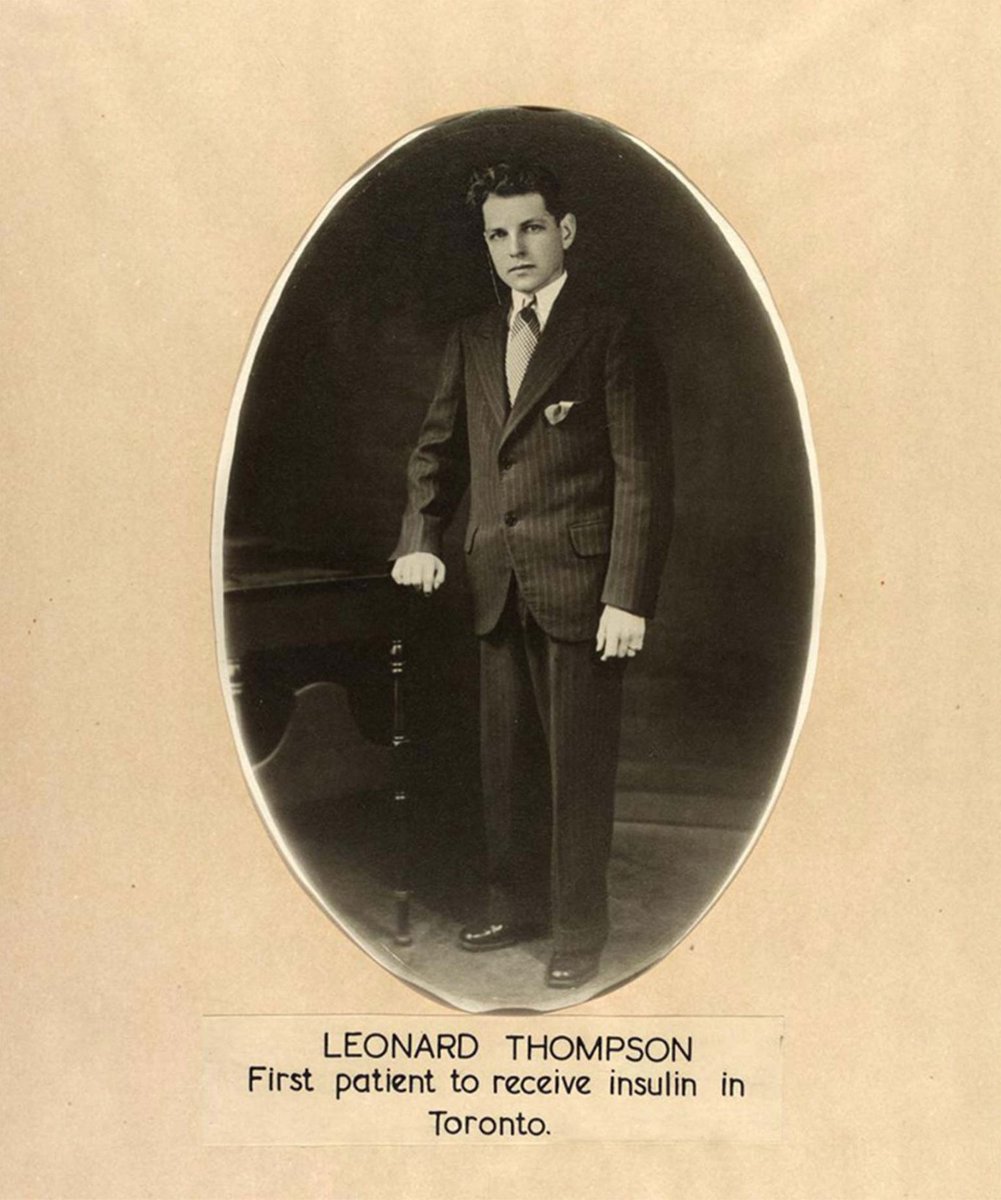

💉 Today marks exactly 100 years since Leonard Thompson, a 14-year-old boy dying from type 1 diabetes, became the first person to receive an injection of insulin on 11 January 1922.

A thread 👇 (1/6)

A thread 👇 (1/6)

⬇️ Within 24 hours, Leonard’s dangerously high blood sugar levels dropped, but he developed an abscess at the site of the injection and still had high levels of ketones. (2/6)

🔬 Scientists worked day and night on purifying the extract even further, and Leonard was given a second injection on 23 January 1922. This time it was a complete success and Leonard’s blood sugar levels become near-normal, with no obvious side effects. (3/6)

🙌 For the first time in history, type 1 diabetes was not a death sentence. (4/6)

Insulin saved Leonard’s life and countless others over the last century. It’s so exciting to see how far diabetes research has come since then, but there's still a way to go until we find a cure. We're determined to get there - because diabetes is relentless, but so are we. (5/6)

💙 To find out more about the story of insulin and the last 100 years of #DiabetesDiscoveries, head to our website! (6/6) diabetes.org.uk/research/resea…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh