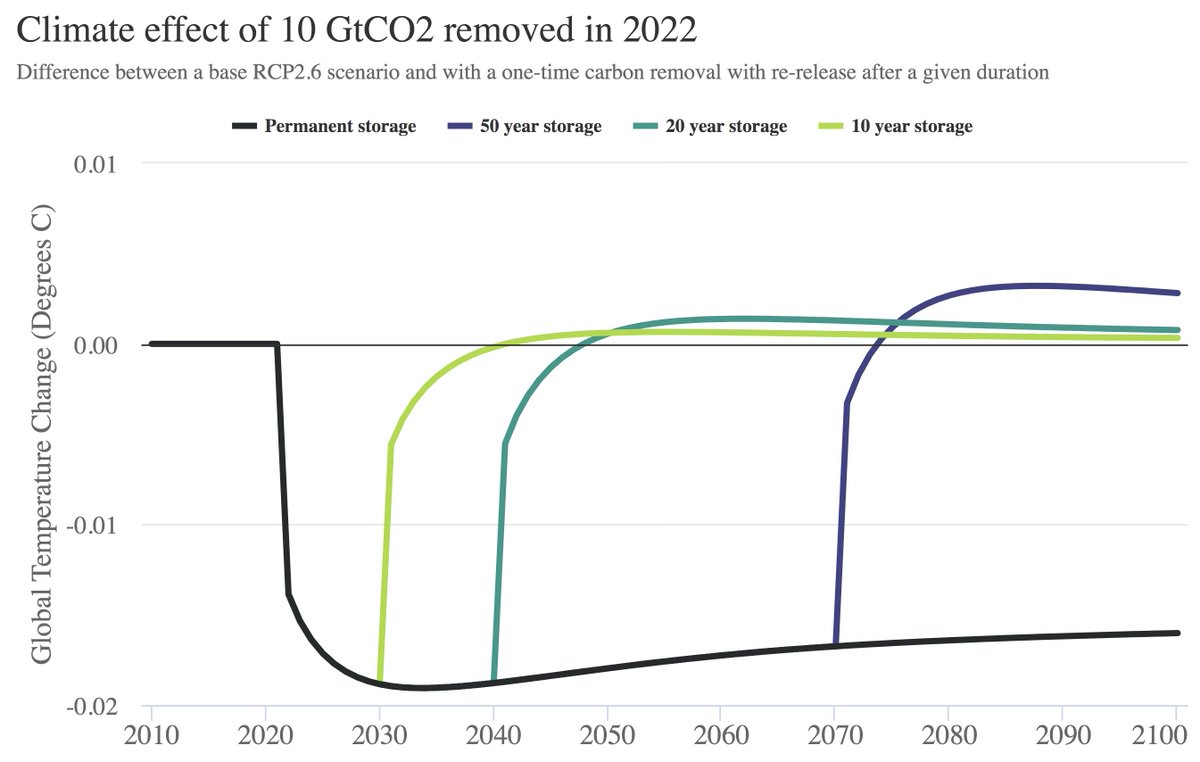

Carbon removal is important, but how long it stays out of the atmosphere makes a big difference on resulting climate impacts. Here are the results of a simple climate model simulating a one-time removal of 10 GtCO2 in 2022, which is stored for 10, 20, 50, or 100+ years:

The figure shows the difference between a deep mitigation scenario (RCP2.6) with and without 10 GtCO2 removed in 2022, which is then re-released after a given period. There are a few interesting dynamics at work here.

Once the CO2 is re-released the climate quickly warms in response, though its buffered a bit by ocean heat uptake times. Somewhat counterintuitively, after re-release we actually end up with more more long term warming than if the CO2 had never been captured in the first place.

This is because the temporary period of lower atmospheric CO2 concentrations results in lower natural carbon sink (e.g. both land and ocean) uptake, as carbon uptakes increase proportionately with atmospheric concentrations.

This does not necessarily mean that temporary storage is valueless (or actively counterproductive). For example, temperatures peak in the 2070s in RCP2.6, so temporary storage past that peak could effectively lower peak warming (and associated risks).

So why consider temporary storage? Well, most of the carbon removal done today stores carbon in the biosphere (e.g. in the form of trees). This is necessarily somewhat temporary, as trees die and there is no guarantee regions will remain forested in perpetuity.

There are real risks to permanence for biosphere storage in a warming world; for example, many of the wildfires burning through California this year were in forest areas set aside for carbon offsets. Other risks may also grow as the climate warms, e.g.: wildfiretoday.com/2021/12/27/war…

Permanent carbon removal through geologic storage/mineralization is the gold standard, but its prohibitively expensive in most cases (e.g. ~$600/ton) today (though costs are falling). As we move toward a world with more CDR, we need to be willing to pay a premium for permanence.

This modeling was done though my python-based simple climate model SimMod: github.com/hausfath/SimMod

While it does a good job of emulating the warming projections of more complex ESMs, its use of impulse response functions to represent the carbon cycle introduces some limits.

While it does a good job of emulating the warming projections of more complex ESMs, its use of impulse response functions to represent the carbon cycle introduces some limits.

One small correction: the initial graph was simulating a removal of 10 GtC, not 10 GtCO2. I had forgotten that the RCP2.6 emissions input file I was using was in C rather than CO2 when perturbing them. But the shape of the curves is accurate for any given removal quantity.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh