Close to half of all emissions since the industrial revolution have been produced since 1990, the year of the first report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

At current global emissions rates, the 1.5°C budget will be depleted in 6 years and the 2°C budget in 18 years. The per capita sustainable budget compatible with the 1.5°C limit is 1.1 tonne of CO2 per annum per person, i.e. about 6 times less than the current global average.

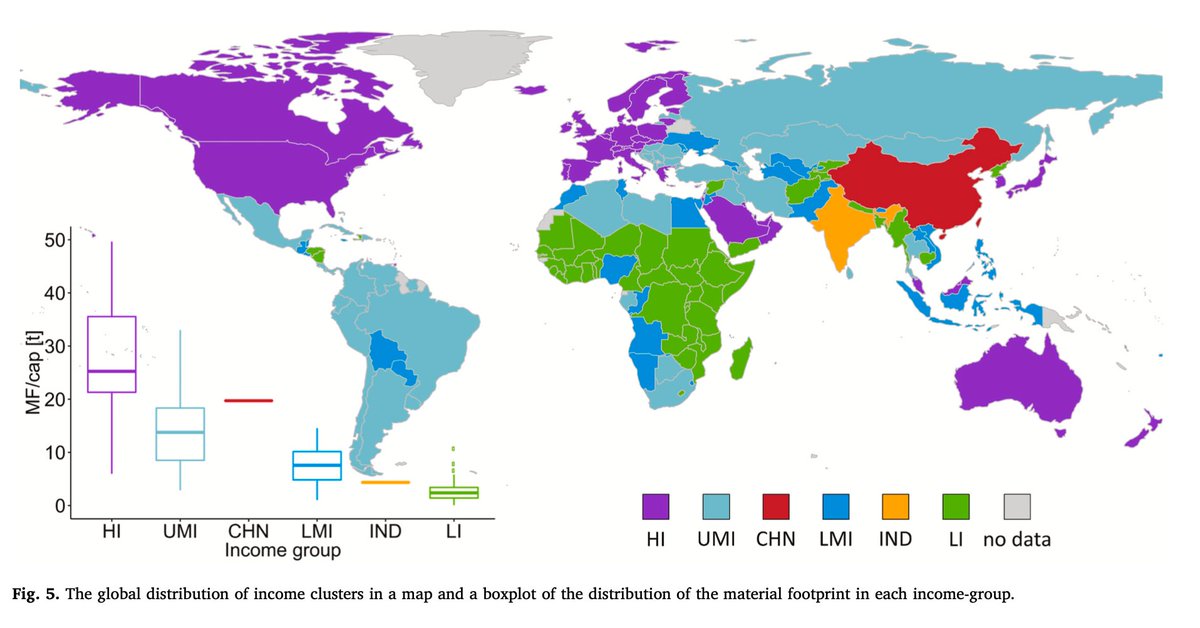

There is a close link between per capita income and emissions, but this link is not perfect: certain regions are more effective than others in limiting emissions associated with a given level of income.

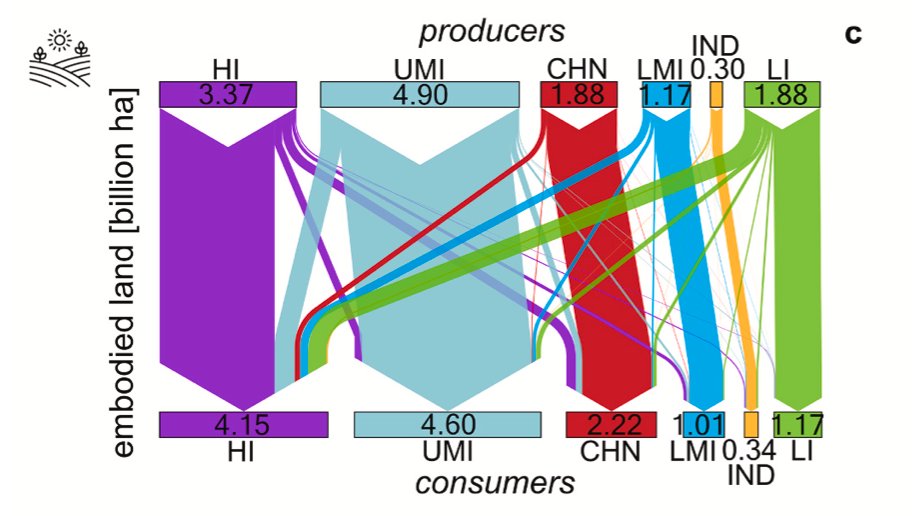

When measuring emissions, watch out for imports and exports. For example, Europe’s carbon footprint (including imported/exported emissions) is 23% higher than its territorial emissions (excluding imported/exported emissions).

The main driver of emission is wealth. At 31.2 tCO2/year/cap, the 10% global richest are responsible for nearly half of total emissions. Compare this to the poorest half of humanity who only represent 12% of total emissions.

The size of the colored areas is proportional to population, showing the extent of carbon inequality, and the fact that only a few people enjoy high-carbon lifestyles.

Since 1990, average global emissions per capita grew by about 7% (and overall emissions grew by 58%), but that average hides wide disparities.

Luxury emissions is not only yachts, jets, and other purchased goods and services, it’s also emissions from the assets that they own.

In 1990, carbon inequality was mostly inequality between rich, high-emission and poor, low-emission COUNTRIES. In 2019, the situation has changed: 63% of global inequality is due to differences within countries between rich, high-emission and poor, low-emission CLASSES.

In rich countries, the bottom 50% is already below the 2030 per capita target (in the US, for example), or very close to it (France). It follows that all emissions reductions efforts should be made by the top half of the distribution.

The existence of carbon inequality means we should apply different objectives and instruments to different population. To put it in a nutshell: degrowth for the rich, green growth for the poor.

For example, a steeply progressive tax rates on polluting stock ownership. Applying a 10% tax rate on the value of carbon assets owned by multimillionaires would generate $100bn per year, about 1.5 times the current estimated annual costs of adaptation for developing countries.

What these numbers show is that the global ecological crisis is not a specie-problem, as the term Anthropocene may suggest; it is rather an issue of wealth concentration where accumulation becomes the main driver of deterioration.

END THREAD/

wid.world/document/clima…

END THREAD/

wid.world/document/clima…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh