Let's make some medieval lye (la lye, lye la lye la lye la lye 🎵). Lye is also known as potash or lixivium. It's a strong alkali and the basic ingredient of soap. Yes, the medievals washed! #teachingmanuscripts #medievalpigments

Lye is completely natural and once again nature is completely AMAZING. A big lovely tree sucks up all the nutrients from the soil through its roots (including potassium). Big lovely tree gets cut down and used for firewood 🙁

The wood all burns away and leaves nothing but ashes. BUT - the ashes contain lots of alkali-rich things like potassium and calcium carbonate. You know what's good for getting things clean? Alkali-rich things! (The word alkali comes from the Arabic al-qaly, which means ashes)

And guess what - the medievals knew that the ashes could be put to good use! They knew that collecting lots of wood ash and filtering rain water through it in a barrel would give them a liquid solution that could cut through grease and dirt

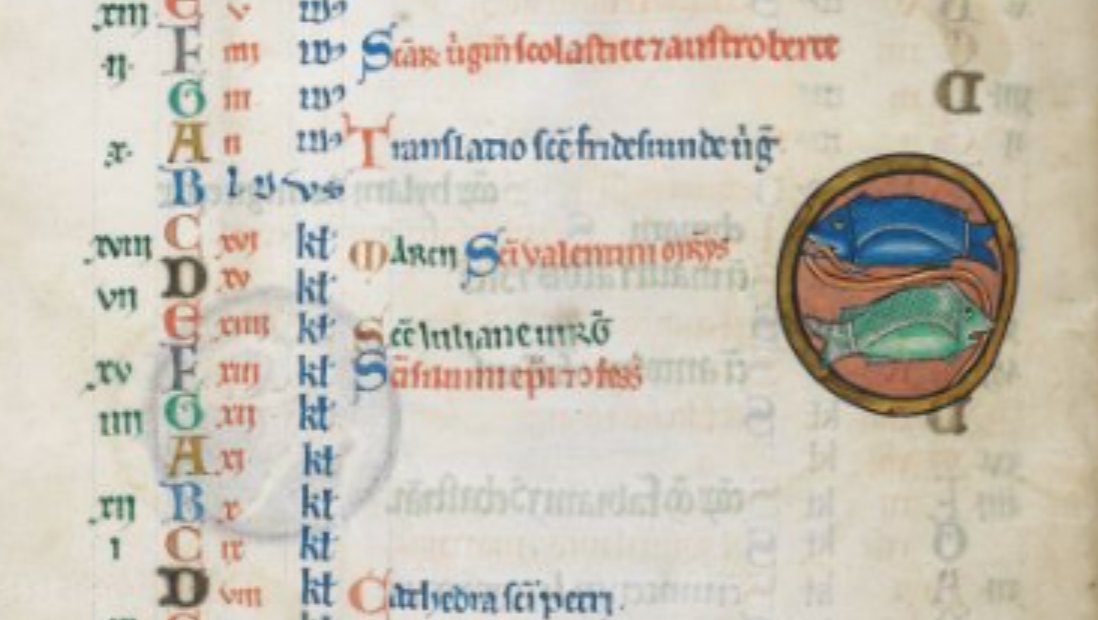

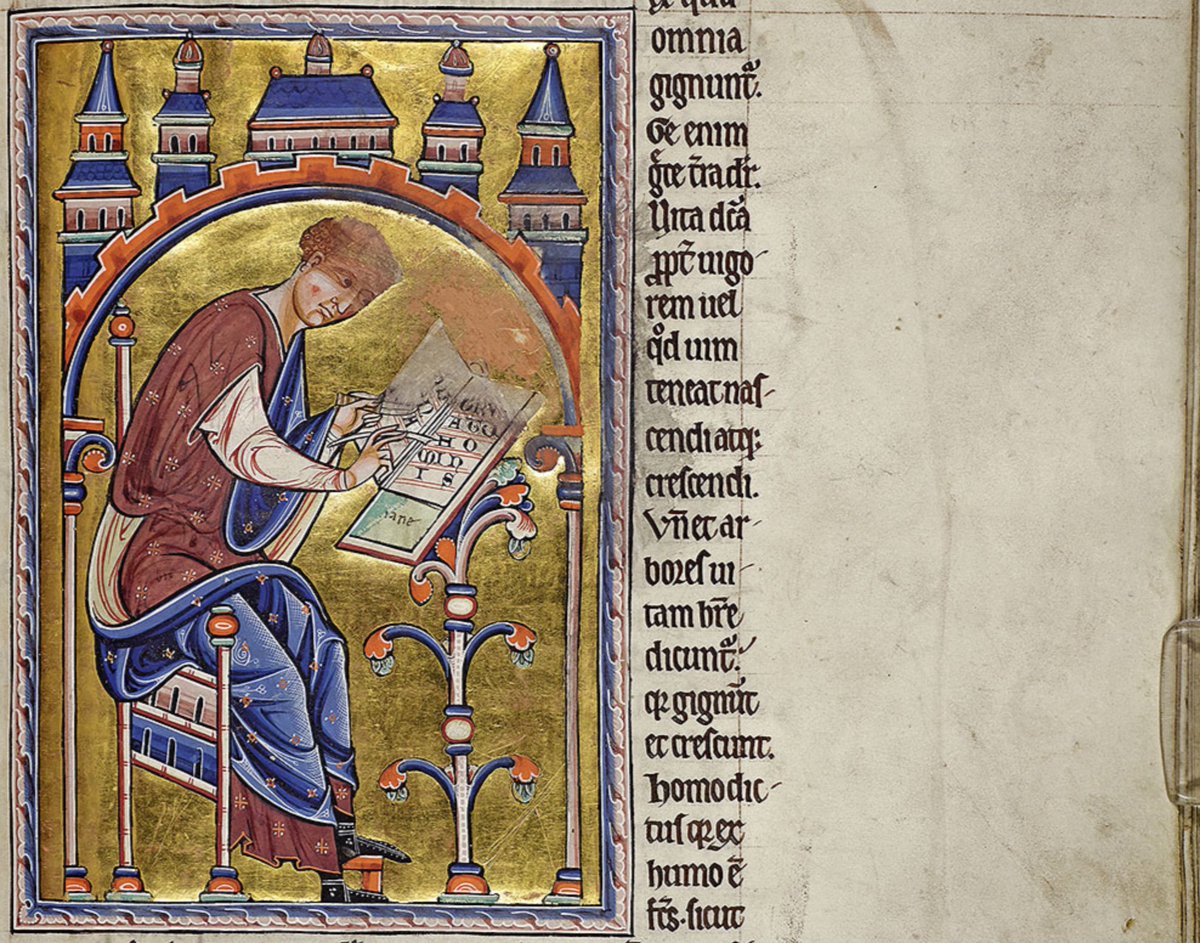

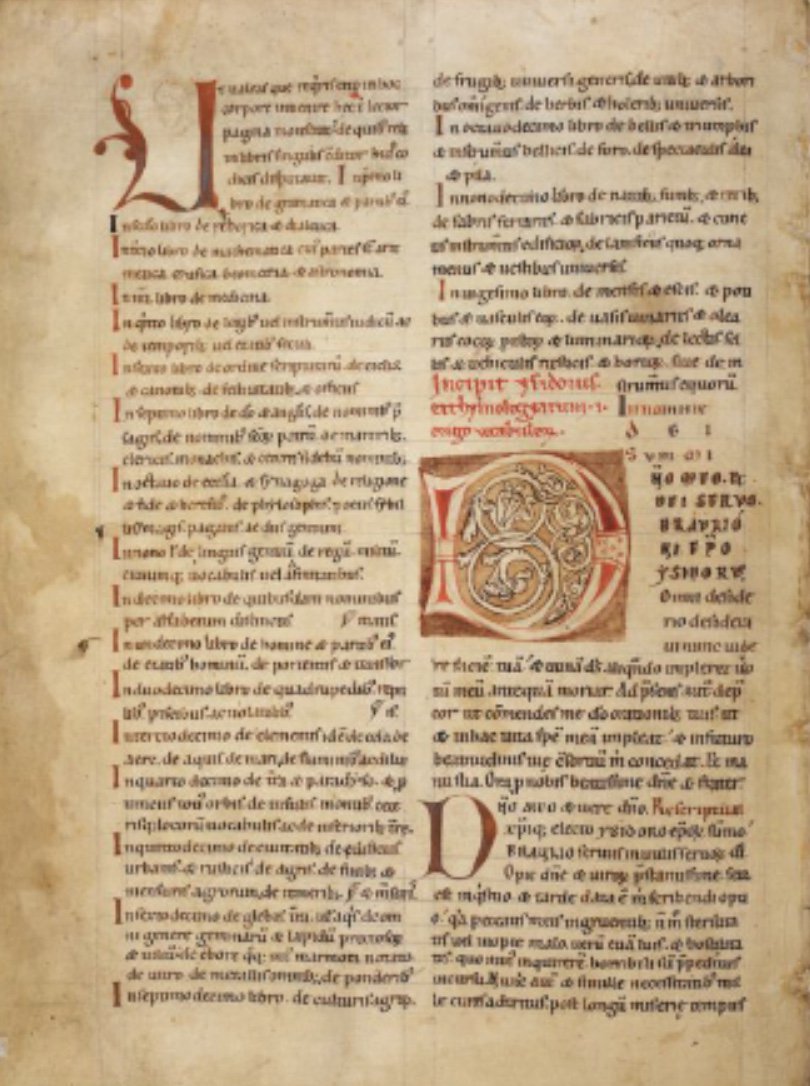

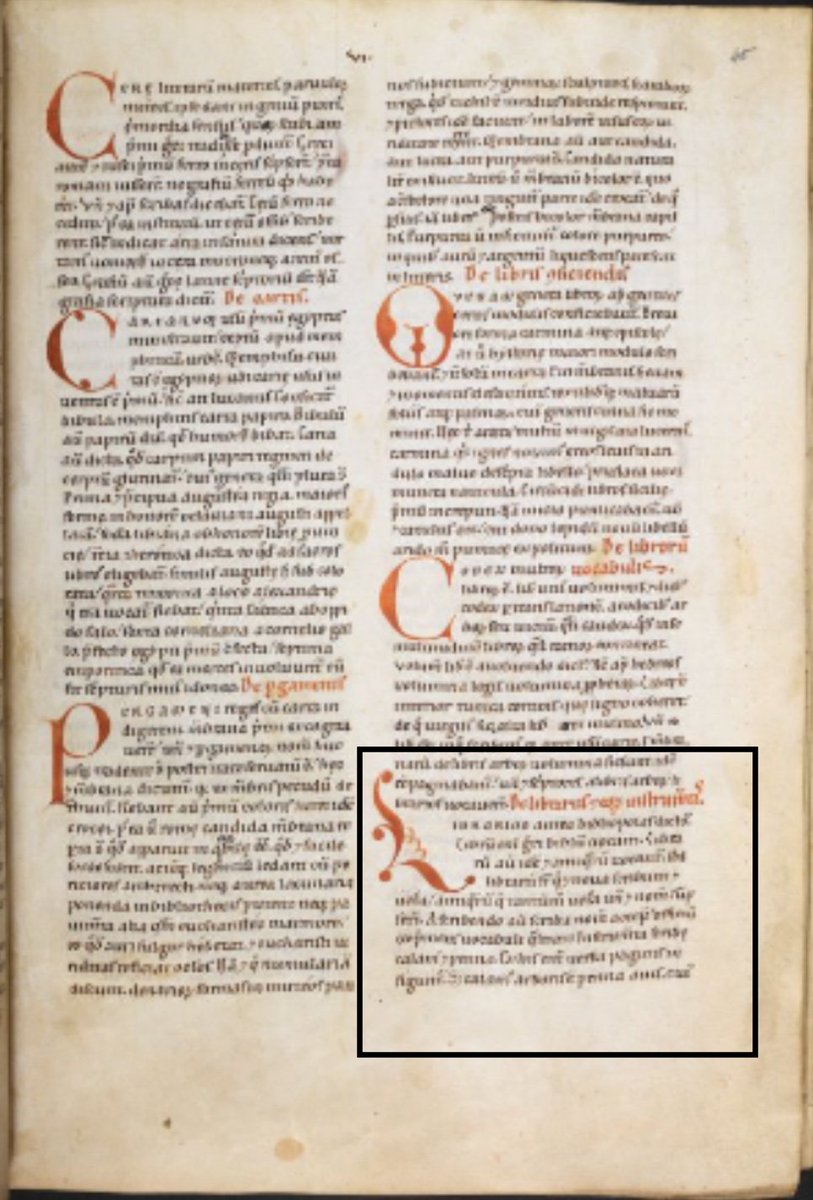

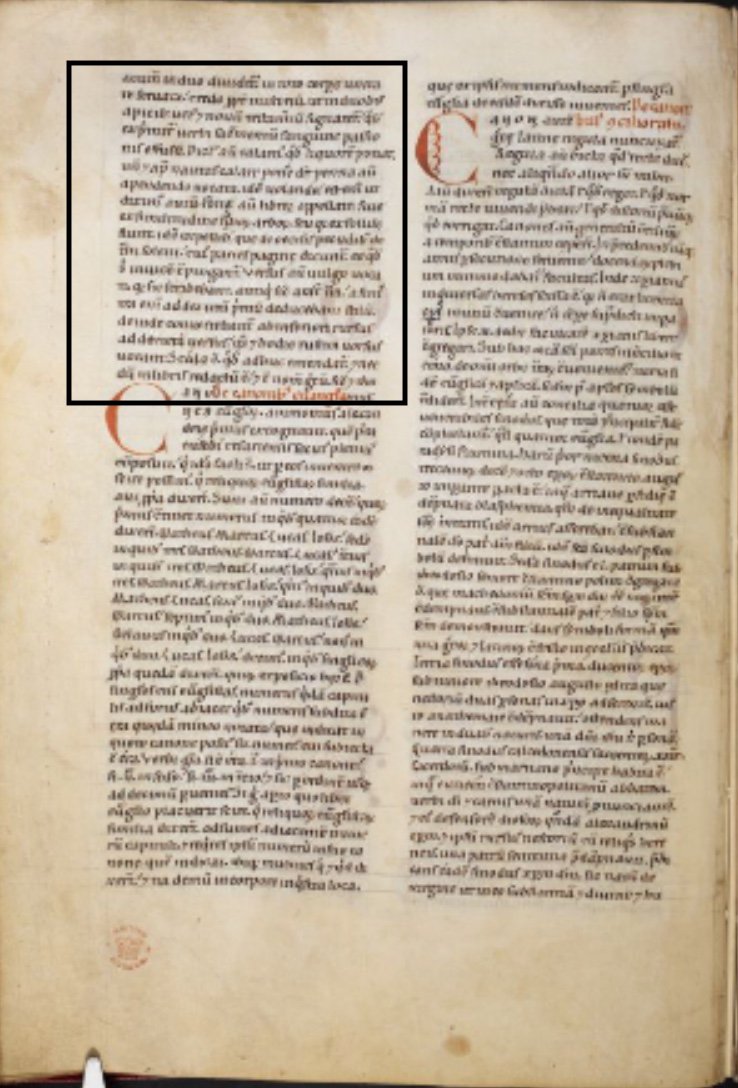

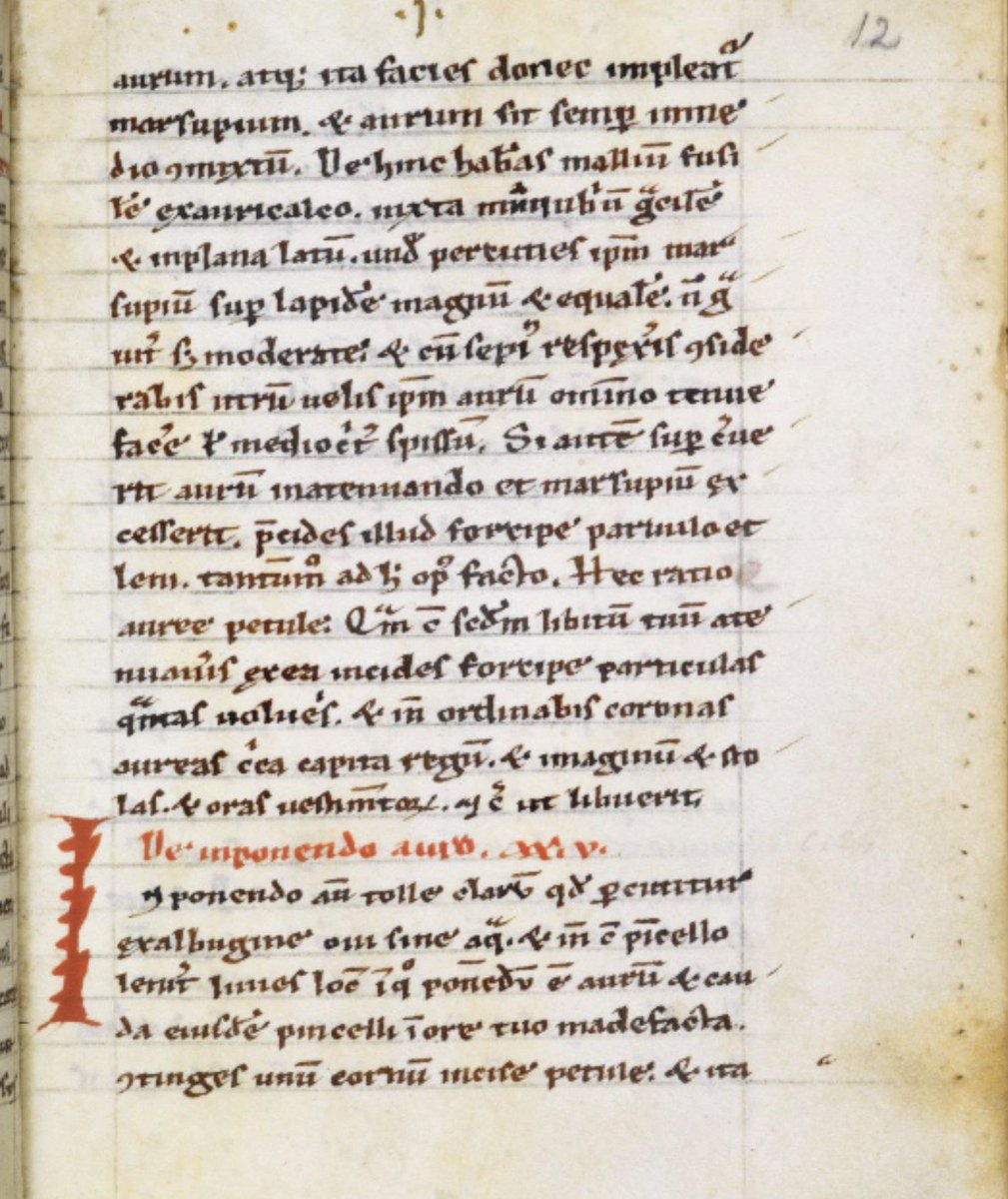

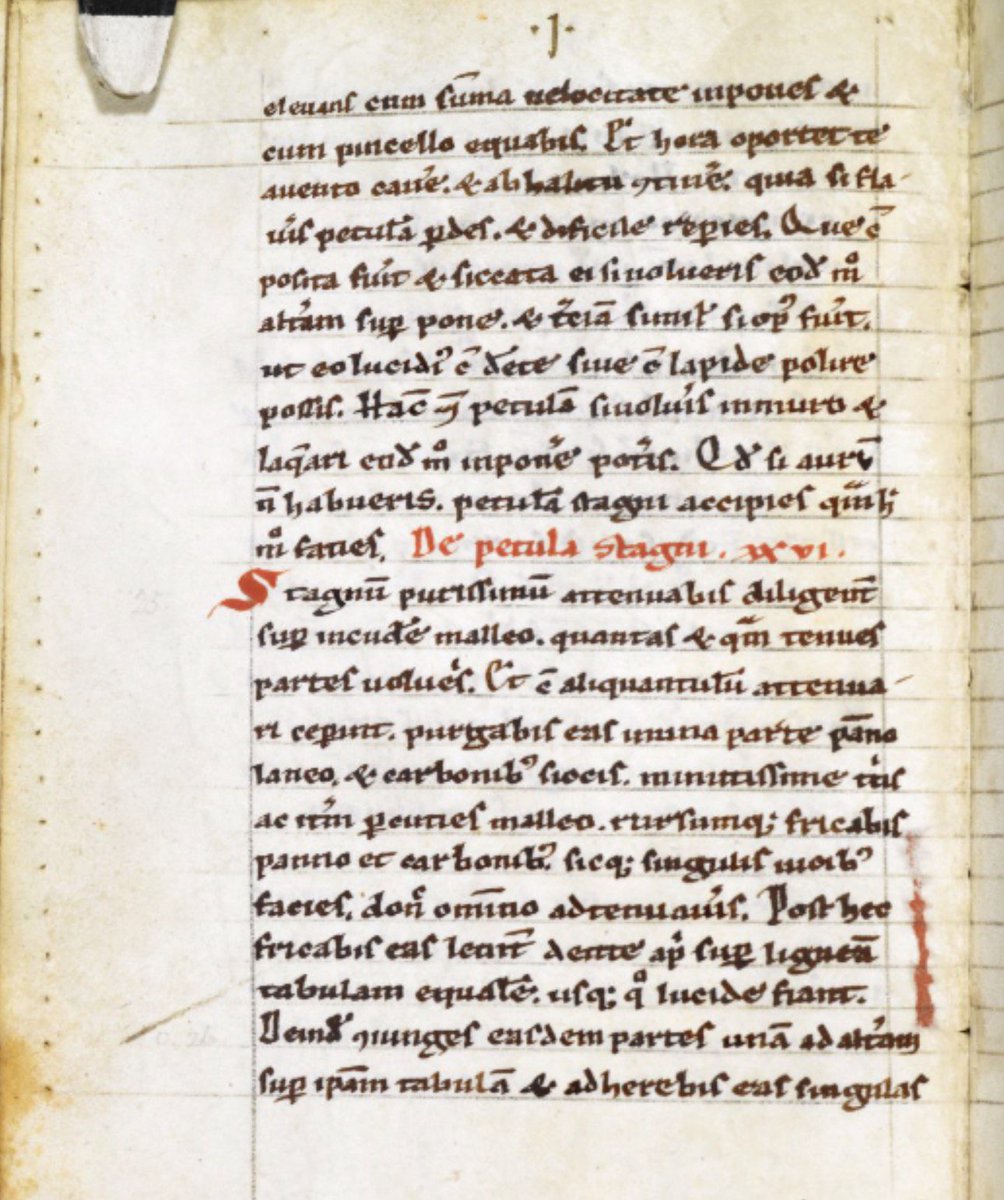

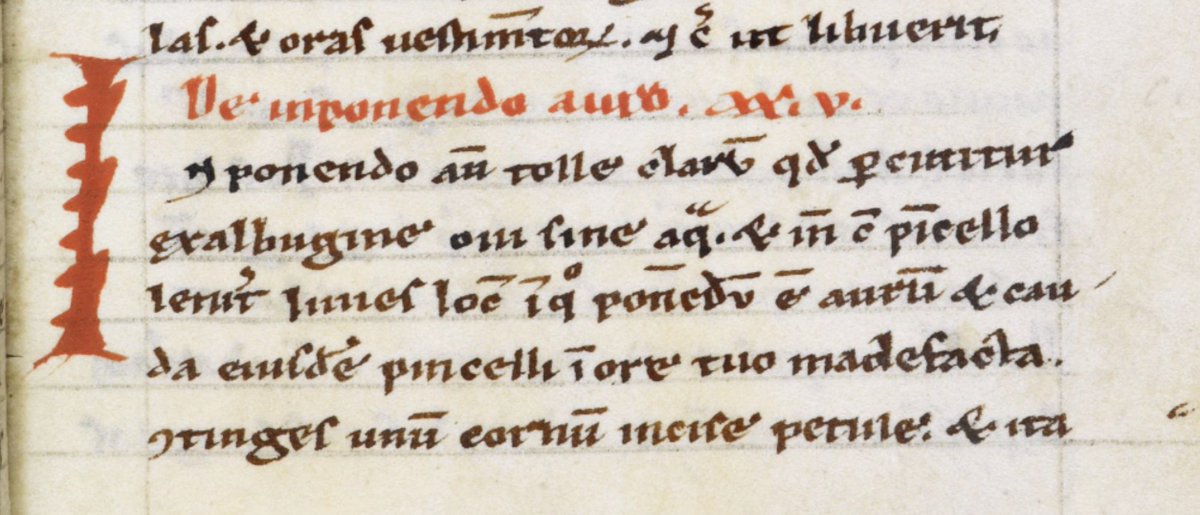

The seventh-century Mappae Clavicula tells us what they did to make lye (in a longer recipe on how to make soap). The lye is called lexiva here. Also, this manuscript is a twelfth-century copy

Fortunately there is also a translated version by Smith and Hawthorne (p. 70) doi.org/10.2307/1006317

As well as using lye for soap, it was used in pigment making. Cennini recommends washing lapis lazuli in lye water and boiling brazilwood in it. It is also used in madder pigment making. I normally buy potassium carbonate as a powder and mix with water -

BUT when I visited my sister recently, I noticed that she had a big bag of logburner ash that they were about to get rid of. Much to her bemusement, I asked if I could have it (NB, it weighed A TON)

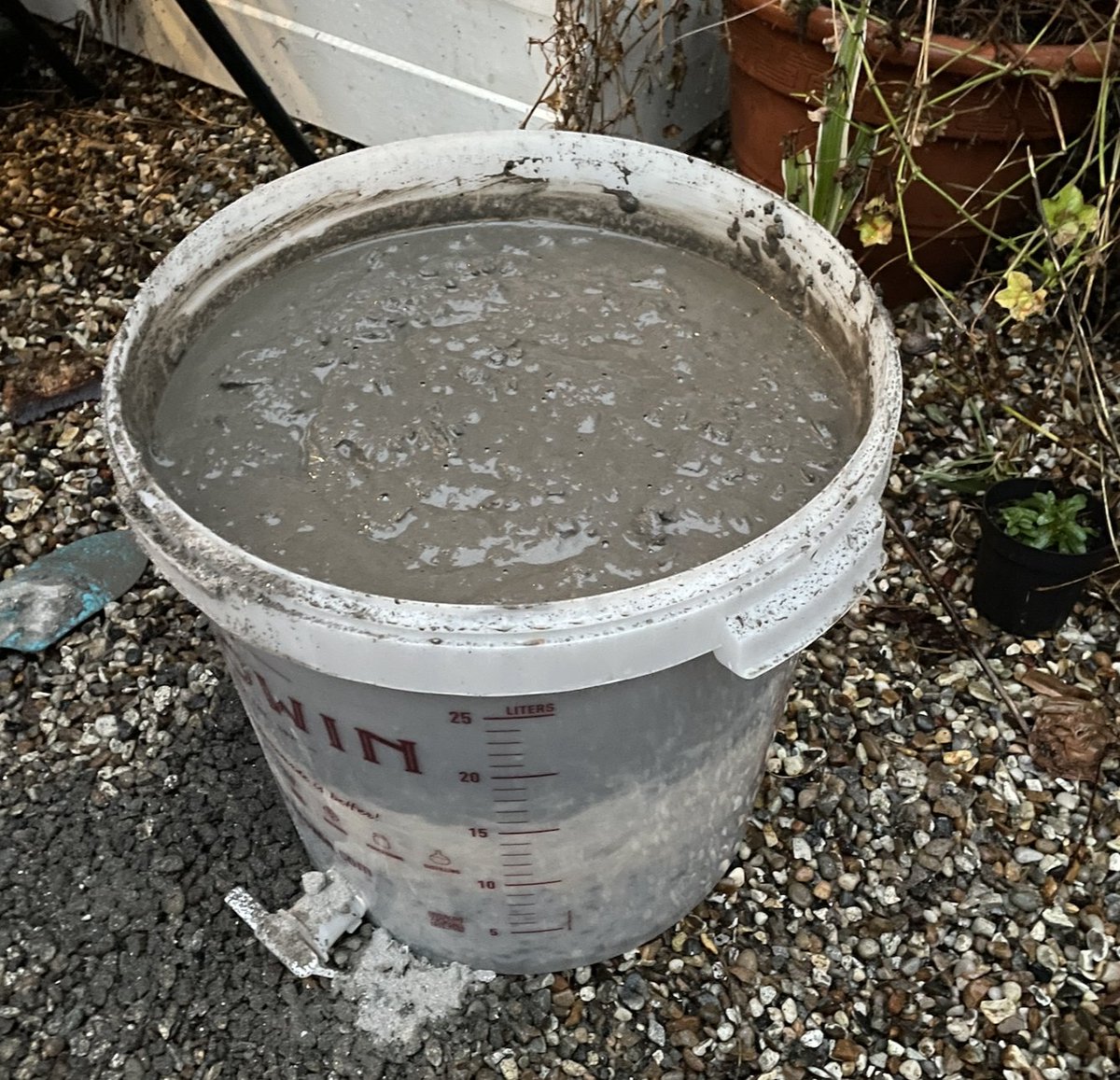

So, big bag of wood ash acquired, I needed to filter it. ‘Borrowing’ my son’s cidermaking tub, I filled the bottom with stones and then layers of straw. Scooping the ash on top, I then poured rain water onto the ash and mixed it in with the ash

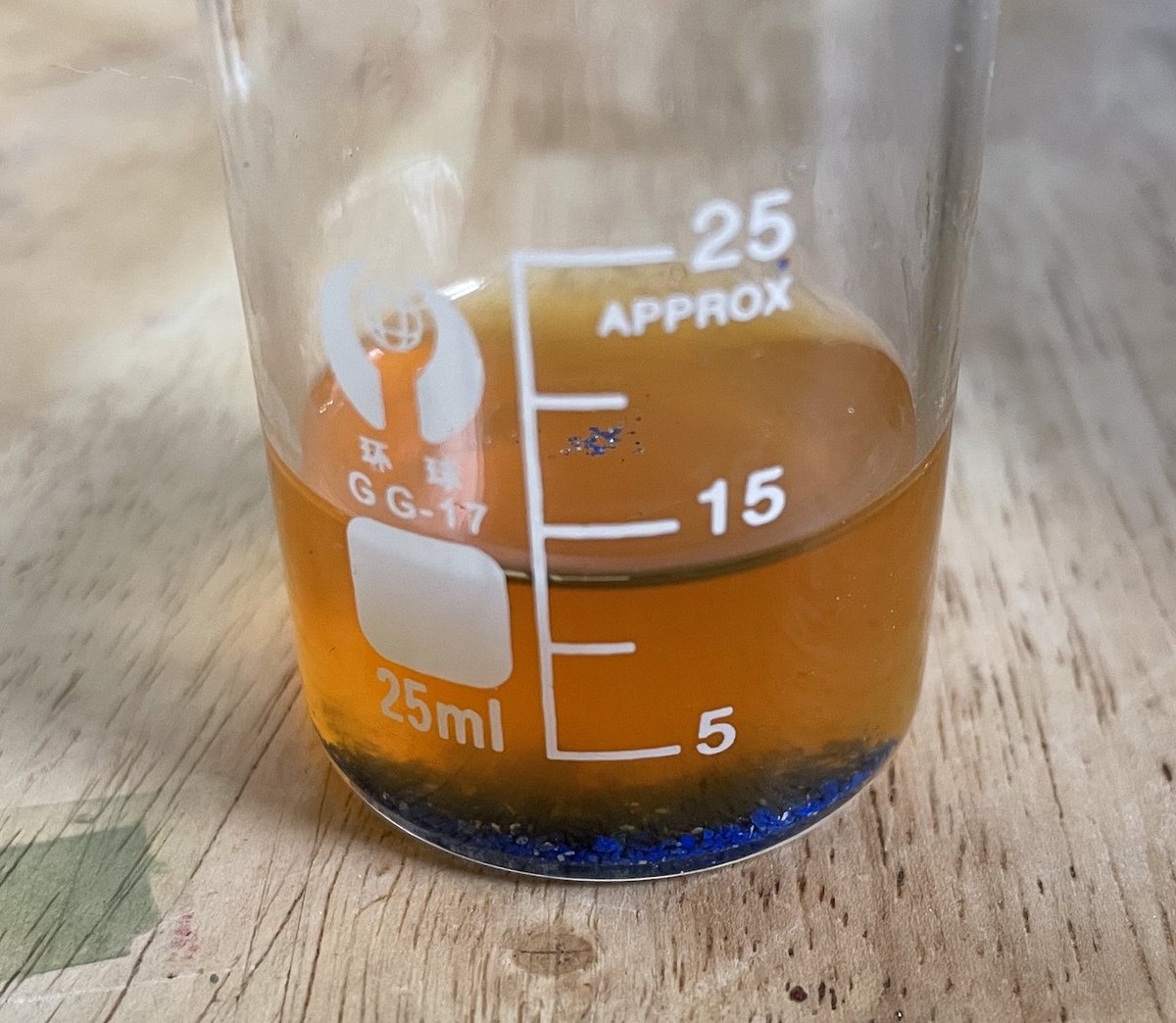

It took about 90 minutes before the lye started filtering though. Testing with litmus paper, you can see that it is indeed alkali. Not a very nice colour though, but this was from the tannins in the ash and straw and cannot be filtered out

It’s pretty strong alkali and I didn’t really want this all sloshing about, so I evaporated it down to a soft sandy coloured powder (very carefully, as it can give you a nasty alkali burn). It’s hard to describe the smell – it’s not nice, but it’s not revolting, sort of earthy

I was unsure about the deep brown colour though. I didn’t want it to discolour my pigments. I tried some lapis that I had recently extracted (but not properly ground yet) in the solution. All seems fine. It actually removed some more impurities from the lapis

So - now I have a very large supply of lye powder that I will use when making my pigments! One day I might even try to make soap. (This is the cheap, common medieval version, of course, known as black soap - a clearer lye can be made with the ashes of marine plants)

There are some great articles here is anyone is interested in making medieval soap:

bit.ly/3Ll56C4

academia.edu/27755720/To_Ma…

bit.ly/3Ll56C4

academia.edu/27755720/To_Ma…

As an aside - there seems to be a bit of debate from various sources I’ve read whether this lye is potassium carbonate or potassium hydroxide. I have no chemical knowledge, so if someone explain, I would be very interested!

(Yes - I do know that this image is actually of wee)

(Yes - I do know that this image is actually of wee)

Ahem! Important correction from @joumajnouna

https://twitter.com/joumajnouna/status/1508857094086303761?s=20&t=Yy5znXQRWchqZQ7Bs-kA8g

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh