1/ What happens to Russian soldiers who refuse to continue fighting in Ukraine? In this fifth and penultimate 🧵 in a series, I'll look at the stories of soldiers who've quit, using intercepted calls and personal accounts translated by @wartranslated.

2/ For the first part, a look at the factors motivating ordinary Russian soldiers to fight in Ukraine, see below:

https://twitter.com/ChrisO_wiki/status/1552921299693064194

3/ In the second part, I've looked at the demoralising effect of inadequate training and lack of equipment for volunteers, as well as their supplies being looted before they even reached the front lines:

https://twitter.com/ChrisO_wiki/status/1553322172847951873

4/ My third thread focused on how Russian soldiers' traumatic battlefield experiences have prompted them to quit:

https://twitter.com/ChrisO_wiki/status/1553833316578631681

5/ The fourth part examines the deep dissatisfaction among Russian troops about their commanders' tactics and behaviour, which have got many of them killed:

https://twitter.com/ChrisO_wiki/status/1554568649268232192

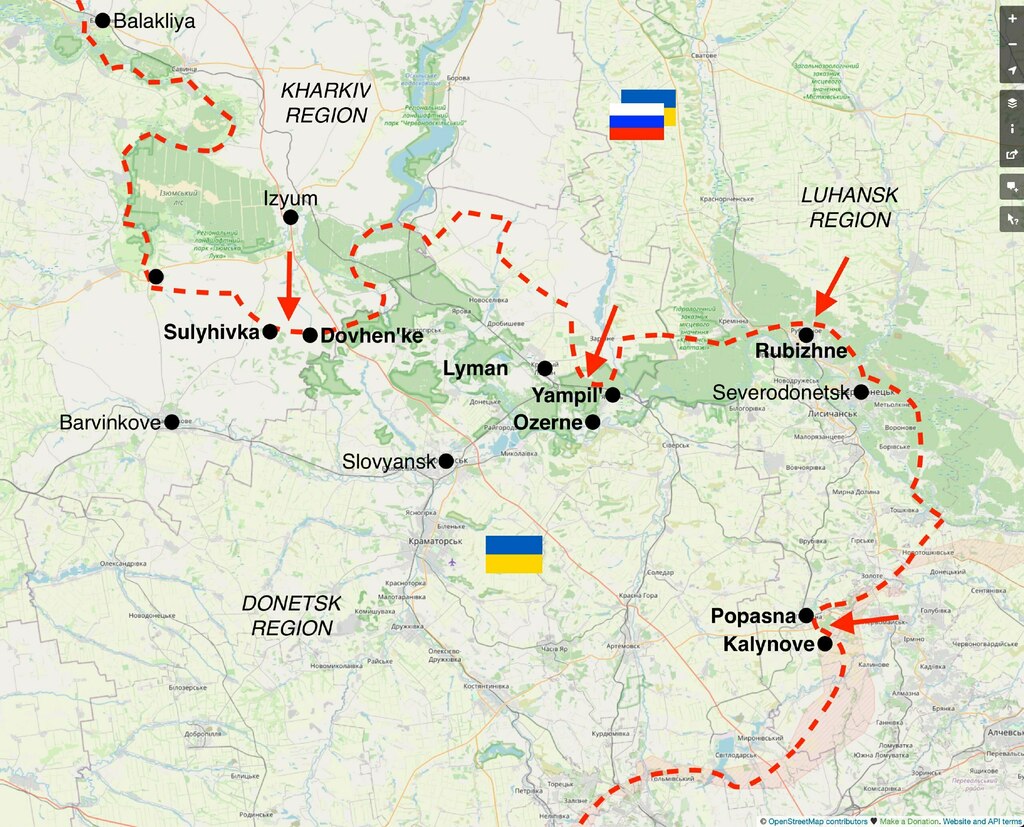

6/ In the course of these threads, I've been looking at the experiences of Viktor Shyaga, a soldier with the 752nd Guards Motor Rifle Regiment. After his unit took heavy losses attacking the Ukrainian village of Dovhen'ke east of Kharkiv in April-May 2022, he refused to fight on.

7/ He was not the only one. Shyaga says that "almost everyone" from his unit refused orders to continue attacking Dovhen'ke, as did the spetsnaz (special forces), airborne troops and Wagner mercenaries. They saw the orders as suicidal.

8/ Intercepted calls published by Ukraine show many Russian soldiers quitting because of their appalling battlefield experiences. One said, "No one is returning. Everyone’s quitting. Everyone’s fucking off. Why is nothing shown on the TV, I don’t know, it’s a real massacre here."

9/ Another said: "We have a fuckton of refusers!" Out of a likely battalion tactical group (600–800 men and officers), "around 150 people [are] refusers. All who come back from there, no one even has a right to judge them. Who would want to go to this hell a second time?"

10/ Refusers, dubbed "500s" by the Russians ("200s" are dead, "300s" are wounded), span a wide range of personnel. Officers or foot soldiers, experienced or inexperienced, even special forces and mercenaries – all have quit. The Russian army has responded in a variety of ways.

11/ Shyaga says that "our 752nd regiment’s zampolit [political officer] in Izium was firing from an assault rifle near the feet of those who refused to join assaults. By that time they had around 30 people like that. He preemptively took away weapons from those who had them."

12/ This failed to remotivate the badly demoralised soldiers. Some shouted,"‘Let them shoot! – it’s better to die here, at least the complete body will be passed to relatives so they could bury us properly’."

13/ The soldiers believed that being killed by their own officers was "better than to get torn apart with a bomb and rot in a trench, or (even worse) end up in these scumbag Ukrainians’ captivity."

14/ Appeals from zampolits to refusers have evidently not been popular. Another soldier said in a call: "Yesterday these faggots came, the fucking brigade zampolits, they came in in a big crowd. They came together and said – “you are going [back] to [the] infantry”."

15/ "We told them collectively – “go fuck yourself!”. Flesov flipped out, nearly smashed the brigade zampolit’s face. He was running away from him... I nearly flipped out, I thought if these zampolit faggots come once again, I’ll fucking shoot these scumbags, here in the hangar."

16/ General Valery Solodchuk received an even harsher response when he tried to order his unit to go back into the fight in May 2022. "He started waving his gun, shooting, said – “I’ll kill you if you don’t go there!”. And then this kid says – “Come on, kill!”."

17/ "Fuck, he pulled out the grenade, the pin, and said “Come on, shoot me, come on! We’ll blow up together here”. That’s all. Even spetsnaz were pointing guns at us, and we pointed guns at them too. In short, we almost shot each other, fuck. [Solodchuk] got in his car and left."

18/ In early May, Federal Security Service (FSB) officers arrived at Izium to try a different approach with Shyaga. "They tried very politely to return us to the frontline. I said that we are basically thrown into a senseless slaughter. The Lieutenant said they knew of all this.

19/ "I said it wasn’t just us who refused to assault Dovhen'ke, the spetsnaz [special forces] also refused to assault this village. He answered that ‘They know and they are working on it as well’. He said ‘We do not judge any of you (who refused)’."

20/ The FSB considered using the soldiers for propaganda videos. "Apart from terminating the contract and sending us to Russia they wanted to use some of us to film TikTok videos to show how great it is to be a volunteer at war, to attract new volunteers."

21/ Another FSB colonel, however, took a much harder line. He suggested "taking us out at night and shooting five people each time so that the others would agree to go into attacks." Fortunately for Shyaga and his colleagues, this was not acted upon.

22/ In the end, Shyaga was taken back to Russia and – likely in an attempt to deter others by publicly humiliating the refusers – "our contracts were terminated right in front of our unit." This is not the only instance of commanders using public shaming to motivate their men.

23/ In Budyonnovsk in southern Russia, local commanders put up a "board of shame" listing 300 refusers under the caption "THEY REFUSED TO CARRY OUT COMBAT MISSIONS". (See the thread below for more on the use of boards of shame in Russia.)

https://twitter.com/ChrisO_wiki/status/1547983028068028416

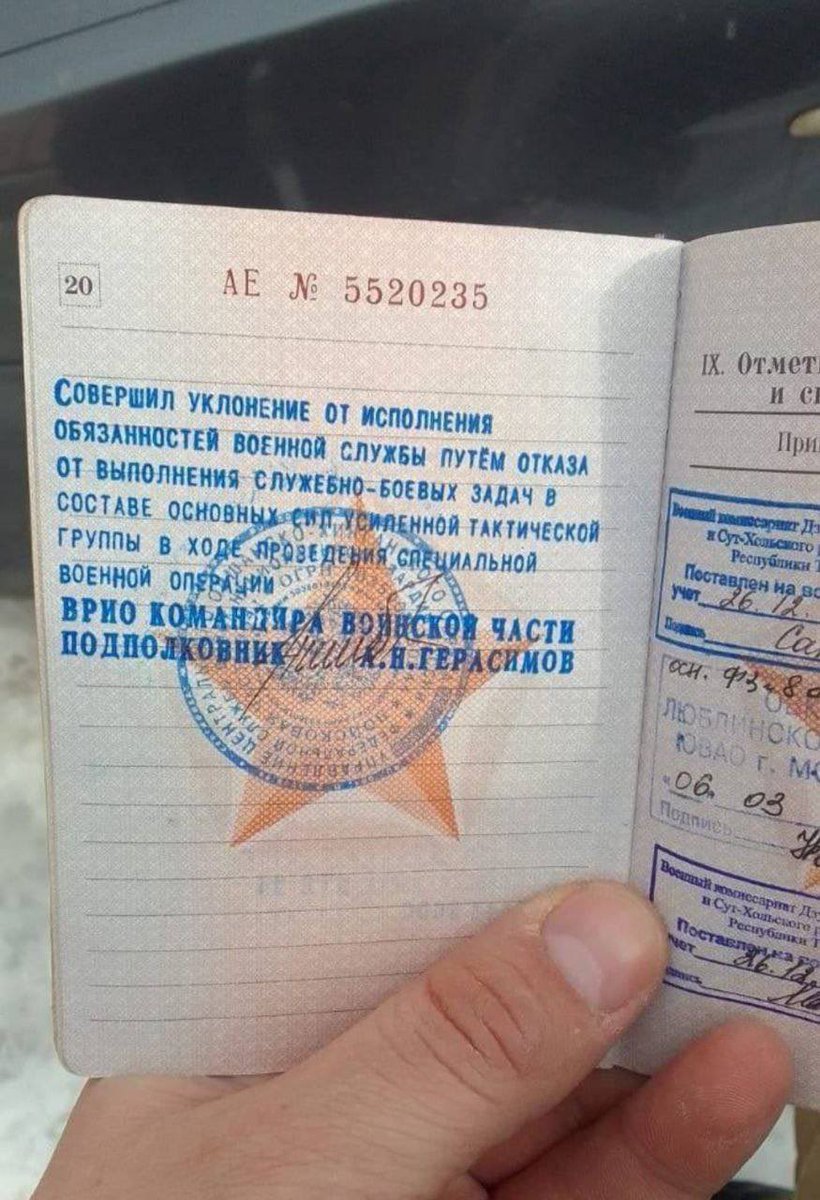

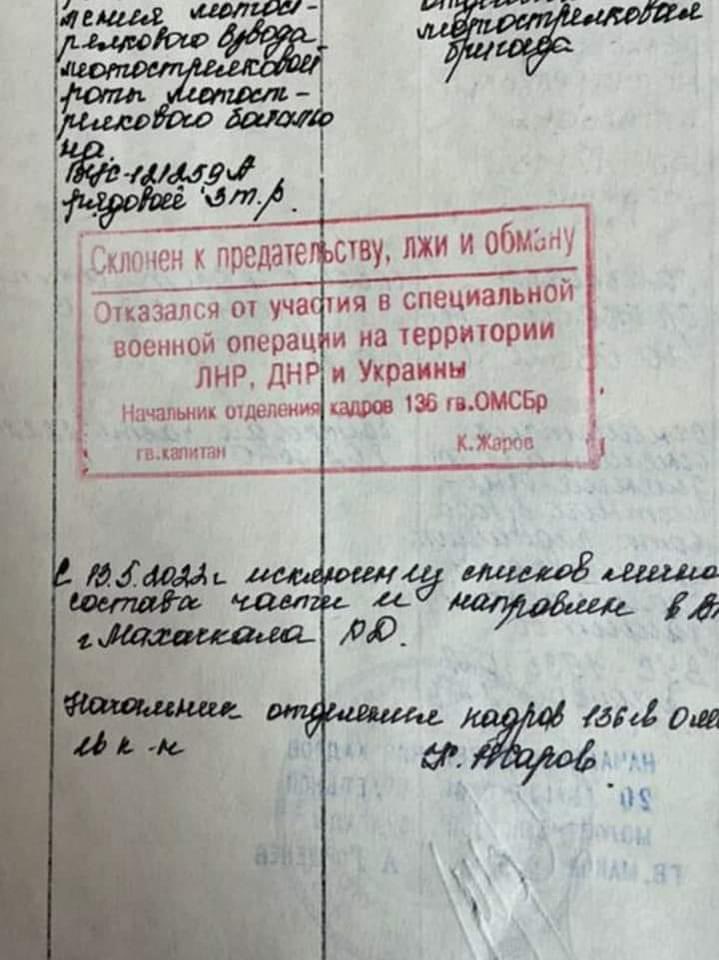

24/ Other soldiers had their military service records stamped with derogatory statements such as "Prone to treachery, deceit and lying. Refused to participate in a special operation". These were likely intended to damage the soldiers' ability to find employment after quitting.

25/ The stamps seem to have deterred some from quitting. One soldier, talking to his mother about why he hadn't left, said: "When they put a red stamp that you refused to participate in the special operation, it’s a shame. A shame for your whole life."

26/ Some commanders have reportedly taken more coercive approaches. According to an intercepted call, soldiers in Belgorod, Russia refused to go to Ukraine. They were loaded into KAMAZs, they were told 'we are taking you to the airport, to send you home'."

27/ "And [command] took them towards Ukraine in locked KAMAZ [trucks]. [The soldiers] figured it out on the way, starting jumping out of the vehicles. ... They figured out something was wrong and started jumping out and shooting in the air.

28/ "Some of them managed to call relatives… they all started running in the direction where they were brought from. They ran 15 kilometers, and while running someone managed to call relatives and told them to call the prosecutor's office and write appeals."

29/ The refusers (who appear to have been Buryats, from one of Russia's ethnic republics) were subsequently held "like prisoners of war". According to one of them, they were “kept locked up in a garage” and “fed some gruel once a day”.

30/ The wives of the soldiers recorded a video appeal saying their husbands had not been brought home despite terminating their contracts. 150 were put on a bus home, but were sent back to Ukraine while the FSB 'spoke with' the wives.

31/ Dozens of soldiers were imprisoned in the city of Luhansk, where they were guarded by Wagner Group mercenaries. "They told us that mines had been placed outside the military base and that whoever tried to flee would be considered an enemy and shot on the spot."

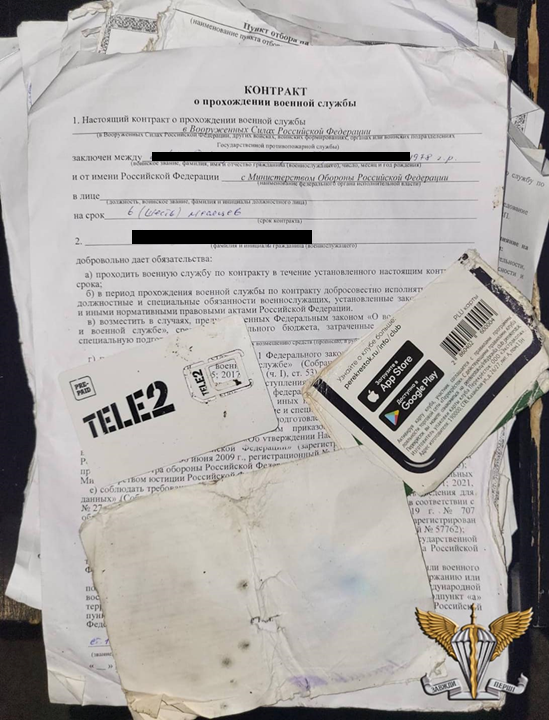

32/ Soldiers have to go through a bureaucratic process to resign from their contract. It's not automatically terminated by a resignation letter. The soldier must provide his commander with a reasoned explanation of his decision.

33/ The commander then sends a dismissal letter to the local military district HQ, along with his opinion/recommendation and the soldier's testimony. The district command then makes a final decision about the case.

34/ This isn't always a speedy process, as there is no defined time period within which it must be completed. The outcome also isn't guaranteed, as the soldier must provide a 'good reason' for resigning - but there's no clear definition of what counts as a 'good reason'.

35/ Resigning soldiers are penalised in various ways – they forfeit pensions and benefits given to veterans, as well as veterans' certificates, which may help them to find employment and get better education for their children. They are not supposed to be prosecuted or jailed.

36/ An alternative approach is to find a sympathetic doctor who may issue a certificate of medical unfitness. As one soldier put it, "The boys will be going now “on a medical leave”, with whatever health issues they have." He aimed to "do some ECGs and get the fuck out of there."

37/ A few commanders were helpful with resignation requests. One soldier told his mother: "I’m leaving because my commander is assisting me with this ... No one [usually] signs anything, they just leave and that’s it. My commander will just say I’m not needed and let me go."

38/ Commanders have reportedly been inundated with requests to quit. One regimental commander was said to have "had a huge pile already, that’s the only thing I can say for sure. Almost everyone wrote a 'refusal'."

39/ The soldiers in the unit in question faced a potential 30-day wait to hear the outcome of their requests to leave, but in the meantime, they were keeping themselves out of the fighting by "rebelling" and "refusing to carry out orders."

40/ Another unit made plans to leave on their own. "Ten people have prepared a Ural truck to leave immediately on the truck and go towards Belgorod [in Russia] if some shit happens. They filled canisters with diesel, put them in a trunk, got ready."

41/ A sergeant "drove away on a car taken from Ukrainians. He crossed the border, gave up his assault rifle, armour, weapon, made it home and they cannot even start a case against him ... since he has ... no previous criminal case, nothing, so they can’t dig anything up."

42/ It's likely that manpower shortages have made commanders reluctant to grant requests to leave. One commander "gives no fucks, because if we are removed someone else needs to be brought in, otherwise everything will be [ruined]. He says: “there is nobody to [replace you].”

43/ "The battalion is slowly crumbling, who wants to [leave], leaves. The [battalion commander] said we only have one road out – “We have a loaded machine gun, I’ll go out on the road and start [shooting at you] if you try to get out”".

44/ Other commanders abused their position to accept bribes. The mother of a soldier serving with the 126th Coastal Defence Brigade bribed an officer to transfer her son to a safe military base, but was distraught to learn that the promised transfer hadn't happened.

45/ "How’s it possible? They took so much money. It cannot be. I don’t believe, I don’t believe, you’ll be transferred certainly, son, please don’t say this, you’ll be transferred! ... No! You’ll be transferred! They took my last money!"

46/ Elsewhere, refusers were subjected to intense psychological pressure. "Here some people wrote reports – [commanders] took their weapons, [the soldiers] are now sitting in a school for four days! Just sitting!"

47/ "They are being told how they are faggots, traitors, worse than shit-eaters! You’re not men, you’re women! And they are sitting there listing to it all, with a hope to be discharged! Fuck no! Until you get to Russia – no fucking way you can get discharged! At all!"

48/ According to one soldier, some refusers "under the threat of violence, were simply driven out to unknown destinations, they have not been seen since". Their fate is unknown.

The number of soldiers who've resigned is unknown, but is likely to be many thousands by now.

The number of soldiers who've resigned is unknown, but is likely to be many thousands by now.

49/ As long as the Ukraine war continues, Russia's army is likely to face a constant exodus of men who no longer want to fight for it. As one put it: "I fucked this army in the mouth together with this country! I won’t be serving [any more in] this fucking dump!"

50/ In my next and final instalment, which I promise will be much shorter 😄, I'll try to answer some of the questions that people have asked about the issues raised by these threads, as well as giving some personal opinions on the Russian army's prospects. /end

Bonus extra thread here!

https://twitter.com/ChrisO_wiki/status/1555817656854499328

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh