🧵on « A case-control study to evaluate the impact of the breast screening programme on breast cancer incidence in England » by Blyuss et al.

onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ca…

#breastcancer #radiation

1/

.@petersasieni @susan_bewley @DanChaltiel @KarstenJuhl @thackerpd @DrJBhattacharya

onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ca…

#breastcancer #radiation

1/

.@petersasieni @susan_bewley @DanChaltiel @KarstenJuhl @thackerpd @DrJBhattacharya

The article’s conclusion suits me: The NHS Breast Screening Programme in England confers at worst modest levels of overdiagnosis.

2/

2/

However, Blyuss et al. did their work on breast cancer incidence, not on overdiagnosis. How could they miss the massive increase of breast cancer incidence caused by mammography-induced cancers?

3/

3/

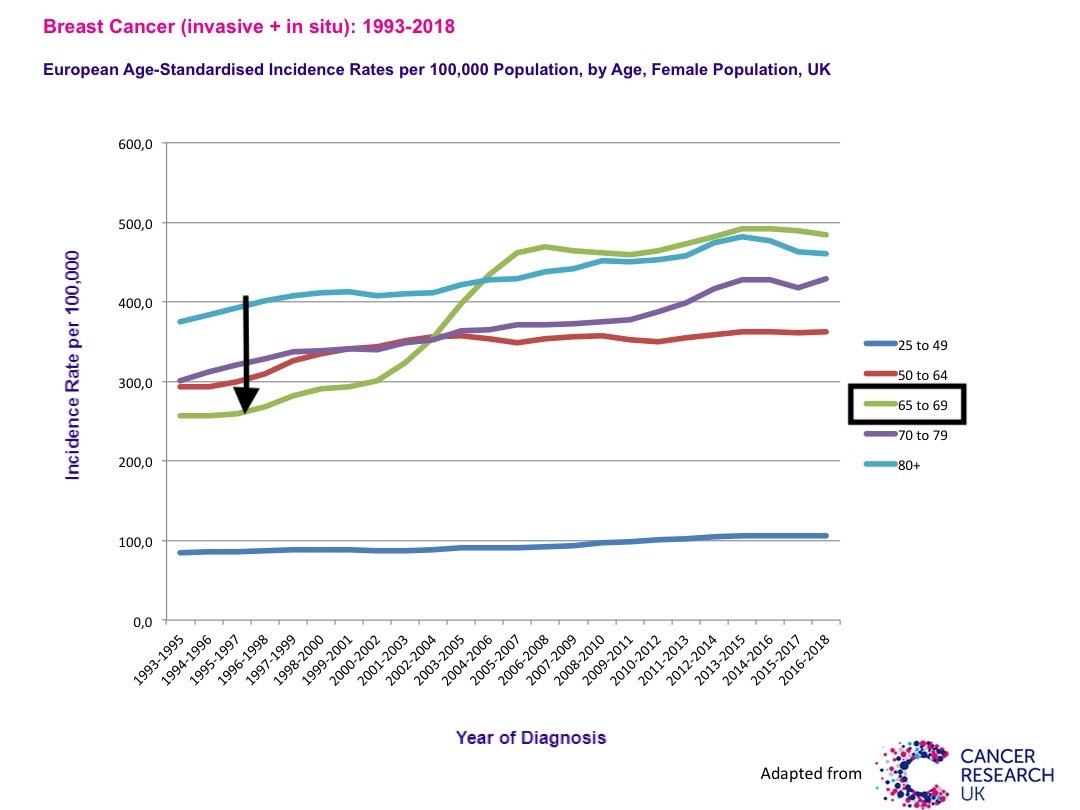

Here is the official data from Cancer Research UK. For invasive cancers: cancerresearchuk.org/health-profess… For in situ cancers: cancerresearchuk.org/health-profess…

4/

4/

Looking at Table 4 of the paper, I see that even without adjustment they found an annual incidence of 379.6 breast cancers (invasive + in situ) per 100,000 in never-screened women of the age group 65-69.

5/

5/

In addition, to make a comparison with the official data, you must take into account mortality after 50 years.

6/

6/

Correcting for 6% mortality, BC incidence for never-screened women aged 65-69 is 402 per 100,000 in 2011. How is it consistent with an incidence of 260 per 100,000 15 years earlier in 1996, before screening was implemented in this age group?

7/

7/

To understand this discrepancy, it is necessary to pay attention to the methods and it seems that the never screened group is heavily biased.

Comparability is achieved between cases (cancer) and controls, but not between screened and never-screened.

8/

Comparability is achieved between cases (cancer) and controls, but not between screened and never-screened.

8/

Cases are obtained through the National Cancer Database. The screening history from cases is easy to obtain.

Controls are obtained by the NHAIS and provide the screening history.

9/

Controls are obtained by the NHAIS and provide the screening history.

9/

However, the small population of never-screened women (12%) is very likely to represent women from disadvantaged populations, with less access to social services. They are most likely underrepresented in NHAIS data.

10/

10/

How can we further show that there is a bias between in the cases/control ratio in never-screened women as compared to screened women?

11/

11/

Let’s compare breast cancer incidence during the first round of screening to cancer incidence in these never-screened women. The first round of screening (prevalent screen) translates in a massive apparent increase in cancer incidence, related to early detection.

12/

12/

If we compare the increase in BC incidence in women aged 50-52 at prevalent screen to never-screened women, the difference is only 23%.

13/

13/

But the increased caused by the prevalent screen was 48% in the 50-54 age group in the whole population of England and Wales in 1993 where only 70% of women were screened compared to 1987. And mammography was less sensitive then than in 2011.

14/

14/

These results mean that even in the first years of screening the case/control ratio in the never-screened population is not representative of the general population. Things may be worse in older women who have never attended screening.

15/

15/

In conclusion, the effect of breast cancer screening on breast cancer incidence cannot be assessed in this study since the never-screened group is totally biased. The authors were fortunate not to find underdiagnosis rather than a small excess of cancers in screened women.

16/

16/

The effect of screening is better assessed in the whole population before and after the introduction of screening.

17/

17/

In 1996, women in the 65-69 age group, which were not screened and had no mammography-induced cancers from previous irradiation, had an annual incidence of BC (invasive + in situ) of 260 cases per 100,000.

18/

18/

Following screening, in 2006, just 11 years after, women in the 65-69 age group had an incidence of 460 cases per 100,000. This high incidence has never diminished. As no drastic change in cancer risk factor can be identified, the increase can be attributed to screening.

19/

19/

As we have shown (Corcos & Bleyer, NEJM, 2020, Corcos, BioRxiv, 2017) most of the increase occurs after mammograms and therefore is not overdiagnosis.

biorxiv.org/content/10.110…

END

20/20

biorxiv.org/content/10.110…

END

20/20

@threadreaderapp please unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh