New paper on pandemic UI!

TLDR expanded benefits had large spending & small job-finding impacts

Implications

1) Unemployed hhs have high MPCs *even* though also have high liquidity. Inconsistent with rep agent model

2) Temporary benefits promising tool for future recessions

TLDR expanded benefits had large spending & small job-finding impacts

Implications

1) Unemployed hhs have high MPCs *even* though also have high liquidity. Inconsistent with rep agent model

2) Temporary benefits promising tool for future recessions

https://twitter.com/nberpubs/status/1559342991692767232

New paper with @Dan_M_Sullivan @pascaljnoel @JoeVavra using #JPMCInstitute data

Reduced-form findings similar to prior drafts so I’ll focus here on what’s new which is that we organize the results into three lessons

Reduced-form findings similar to prior drafts so I’ll focus here on what’s new which is that we organize the results into three lessons

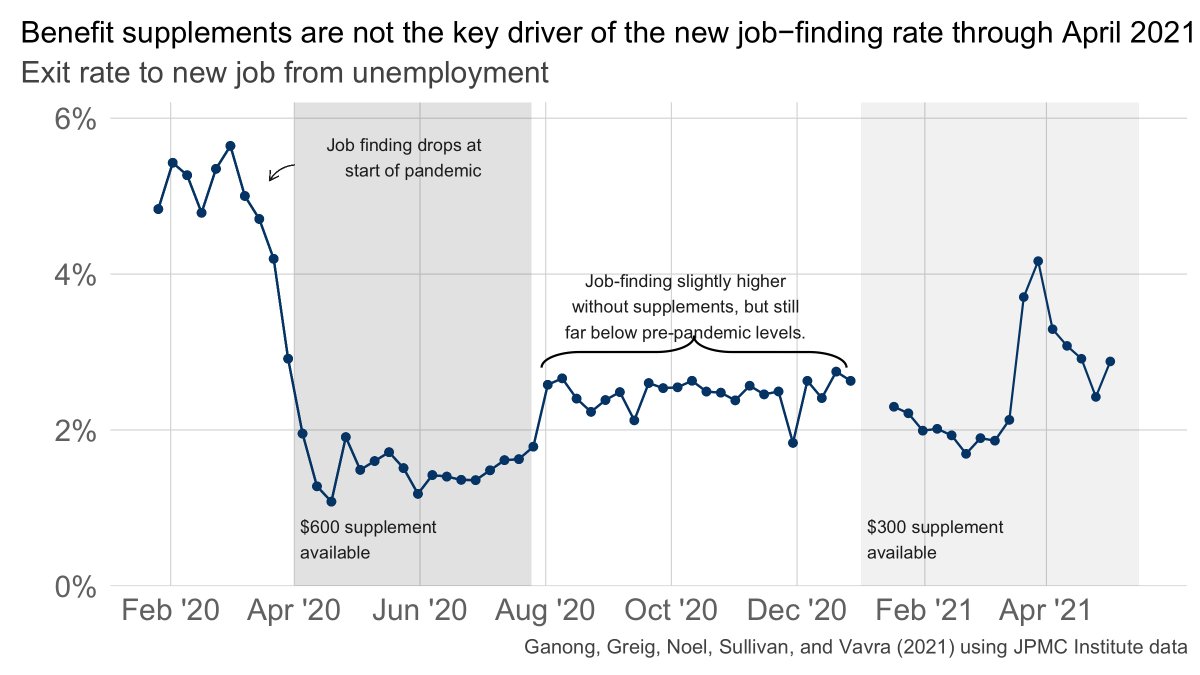

Lesson 1: Benefit supplements are important for explaining the dynamics of spending, but *not* the dynamics of employment.

Lesson 2: Most prior work has focused on the idea that hhs who become unemployed are likely to spend transfers because they are low liquidity.

In the pandemic, however, there’s a wrinkle. Gov’t transfers are so large that the unemployed are *not* low liquidity during this time period. In fact, mean acct balances of unemployed workers up more than 50%!

We find high MPCs; yet the standard account of high MPCs (through low liquidity) is *not* applicable. This suggests that persistent behavioral characteristics—and not just current liquidity—are important for understanding household consumption patterns.

Lesson 3: What can we take away for regular recessions? (hopefully no more pandemic recessions!)

Part A: most prior research focuses on long-term or permanent benefit increases, but both the pandemic and other recessions may warrant *temporary* increases. These temporary increases discourage employment less than permanent ones do.

Part B: consider the extreme case of a policymaker who cares *only* about stabilizing aggregate demand (attaches no value to helping unemployed).

They should give $2K severance to every unemployed worker (on top of regular UI) before giving even $1 of universal stimulus

They should give $2K severance to every unemployed worker (on top of regular UI) before giving even $1 of universal stimulus

What’s the intuition? That 2K of severance is more likely to be spent than even the first dollar of a stimulus check. And employment effects are likely to be minimal.

To be clear, our point is not that severance is the best way to support unemployed hhs, it’s that in addition to the normal trade off (helping U hhs vs moral hazard), there’s another reason to want to expand UI during recessions.

Also, this paper has benefited a ton from comments and questions on #econtwitter. Please definitely tag me if you have any questions!

Oh dear I had a copy-paste error and missed coauthor @FionaGreigDC!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh