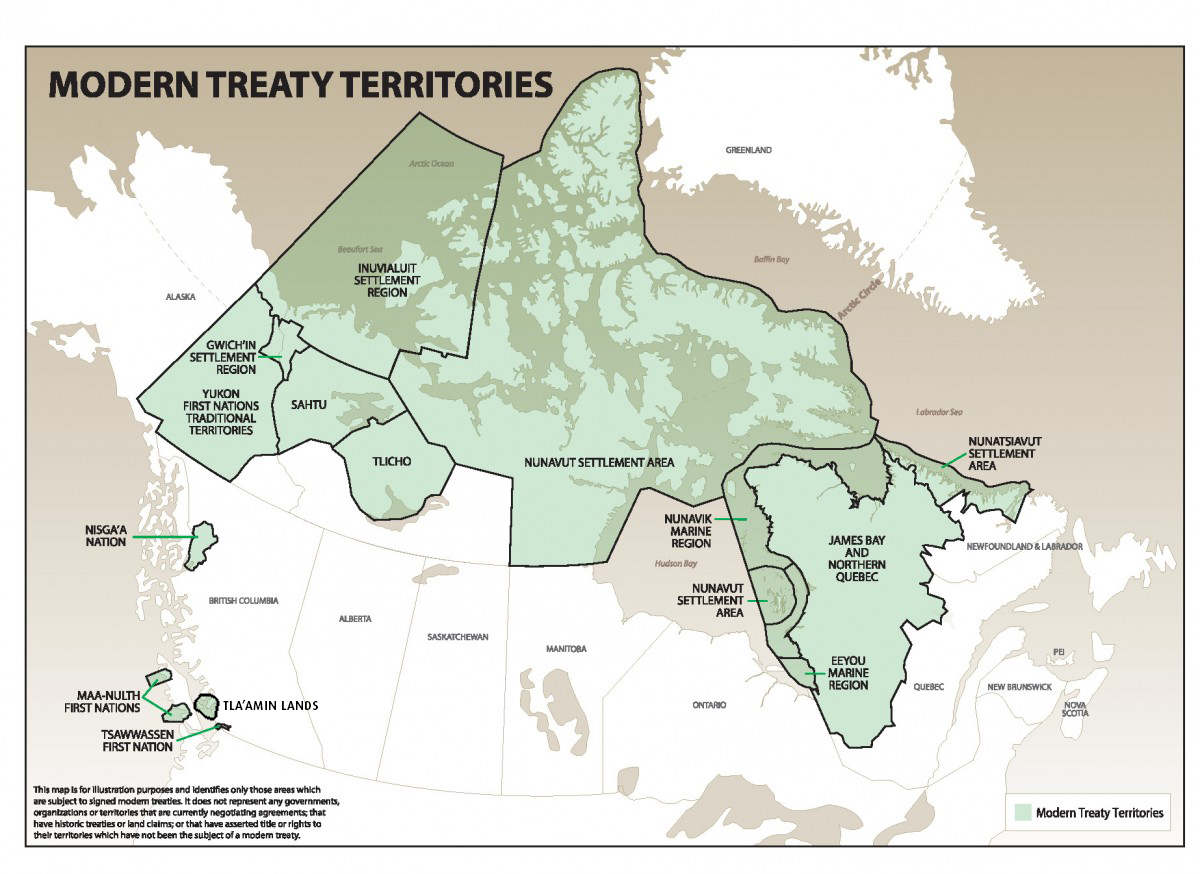

Detailed study in Nature last month of how Mayapan—the biggest Maya city in Yucatán in ~AD1100-1450—responded to a century of drought may provide insight into our own drought-plagued future. nature.com/articles/s4146… 1/18

Mayapan was the capital of a confederacy of smaller states, the most powerful Maya political entity at the time. It rose after the decline in ~900AD of the famous city-states in the southern Yucatán (e.g., Tikal). (map: Masson and Peraza Lope 2014) 2/18

The confederacy was ruled by a council of noble houses in fractious coalitions. Details are sketchy cuz every time a new coalition arose it rewrote the city’s history and put itself at the center. (Image of Mayapan stela by Linda Schele—the text was deliberately obliterated) 3/18

Also, the various houses had different religions and even different calendars. Because religion and the calendar governed state policy, the leadership was constantly infighting, Game of Thrones-style. (📷: Yucatan Tierra de Maravillas) 4/18

The confederacy was a dictatorship. The rulers forced commoners to work and collected the harvest of the surrounding maize fields, gardens, orchards, etc. (📷: Maya forest garden by Mesoamerican Research Center) 5/18

They supervised the construction of the massive 9-km wall around Mayapan and a network of broad roads and the mural-covered temples, halls, and shrines downtown. (maps: Proskouriakoff 1962; Maya Periphery Project) 6/18

In an innovation later matched by Louis XIV and the Tokugawa shogunate, elite families outside Mayapan were forced to live in the city so they could be watched. In other words, these folks were rough customers. 7/18

Two more notable features: 1) the Yucatán Peninsula is a big block of limestone w/o much

in the way of groundwater or rivers (one reason the Maya viewed cenotes [water holes in the limestone] as sacred locations). (📷: Eugene Kaspersky) 8/18

in the way of groundwater or rivers (one reason the Maya viewed cenotes [water holes in the limestone] as sacred locations). (📷: Eugene Kaspersky) 8/18

2) Mayapan had no centralized grain storage--Yucatán is hot and humid, so grain rots quickly. (Question: Ancient Rome, which was also hot and humid, had giant grain warehouses called horrea. Why didn't the Maya?) (📷: horrea on Tiber by maquettes-historique.net) 9/19

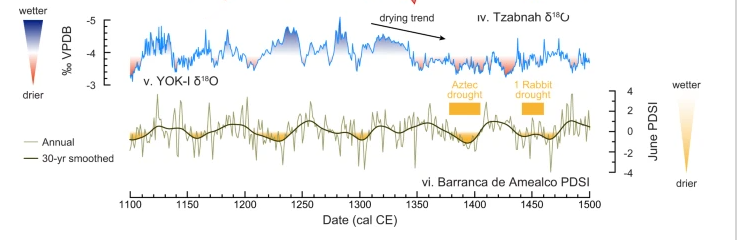

Around ~1340, the Nature paper sez, there's ~100 yrs of awful drought. The authors, Kennett et al., get this from tree rings and speleothems (formations like stalagmites and stalactites, which can trace past climate sorta-kinda like tree rings). (Image: Kennett et al 2022) 10/18

By combining this data with historical sources--Diego de Landa's 1566 history and the Chilam Balam of Mani--and archaeological studies of burials, the researchers can match historical events to drought periods. (Image: Kennett et al 2022) 11/18

In the first super-dry period, the late 1300s, they quickly start running out of food. The leadership responds--by waging a civil-war-ish fight for power between rival factions, in which the Xiu, the old bigwigs, are supplanted by the Cocom & their Canul mercenaries. 12/18

Xiu were burned, chopped to bits, even buried with knives still embedded in their bodies. Even in the language of a scientific report, it's pretty dramatic stuff. 12/18

After a few decades of stability, there’s a second severe dry period around 1450. The Xiu come back and massacre the Cocom, even killing their children. The battle tears up the city and leads to its near-total abandonment—a collapse. 13/18 (oops, messed up the numbering)

But note: the drought didn't *cause* the collapse. Rather, it was the failure of governing elites to respond. Instead of coordinating their efforts, they fought over their own status and privileges. 14/18

Note, too, that the Maya **themselves** didn't collapse. Instead the system reformed into a network of smaller, coastal towns with wetland areas that were good for agriculture. Ultimately the peninsula was split into 15-20 small states. 15/18

These states also went through decades of drought. But they were far better organized internally, and so they nonetheless thrived--until the ultimate calamity, Europeans, showed up in the early 1500s. 16/18 (Image: UK cover of my book, 1491 #shamelessplug)

The Yucatán drought was a “mega-drought” like the one we’re heading into in the North American West. Yucatán was one of the more densely packed urban places in the world at the time. Ultimately, the Maya survived and even thrived despite the drought. 17/18

The main problem they faced was not so much the drought itself, as their own political system. The “collapse” of Mayapan was entirely unnecessary. (My thanks to @pkedrosky for drawing this article to my attention.) 18/18

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh