Built in 420BC, the Tetrastyle (4 columned) Ionic Temple of Athena Nike, jointly dedicated to these two goddesses is one of the most prominent as you ascend the Athenian Acropolis.

#athenanike #Acropolis #Athens #Greece #ionicarchitecture #greekarchitecture

#athenanike #Acropolis #Athens #Greece #ionicarchitecture #greekarchitecture

To people visiting the Acropolis today, it may come as a surprise to discover that this temple's position is not as permanent as it now appears.

It has in fact disappeared and reappeared multiple times in recent history.

It has in fact disappeared and reappeared multiple times in recent history.

The first was before the 1687 siege of the Acropolis by the Francesco Morosini's Venetian army, when Turkish defenders dismantled the temple & used its fabric to reinforce the bastion, fortifications in front of the Propylaia, and convert them into cannon emplacements.

The defensive walls into which parts of the temple were built had been badly battered by the Venetian bombardment, and other pieces lay around amongst centuries of rubble and could not be identified by visiting antiquarians as late as 1837.

German archaeologist Ludwig Ross had the task of restoring monuments on the Acropolis, with architects Eduard Schaubert & Hans Christian Hansen. The Temple of Athena Nike was the first monument on the Acropolis to be restored, and by 1835 all discovered parts had been collected.

In 1836 Greek archaeologist Kyriakos Pittakis took over & completed the rebuilding of the temple in 1844. He also added three of the four copies of the "Elgin Marbles" parts of the frieze, donated in 1845 by the British Museum; the fourth copy was broken during the assembly work.

In 1934 a survey of the Acropolis monuments revealed that the temple and the bastion it sat on were unstable and in danger of collapsing. It would have to be dismantled & rebuilt (again). The task was entrusted to civil engineer Nikolaos Balanos.

From 1935 Balanos dismantled the Temple of Athena Nike, and excavated the bastion down to the bedrock. It was then that the remains of the older temple were discovered. He took the controversial step of using concrete to support the bastion and as a foundation for the temple.

Balanos was succeeded by Greek architect and archaeologist Anastasios Orlandos , who re-did a lot of the work previously carried out by Balanos which he believed to be incorrect. The reconstruction of the temple was completed in 1940.

The third removal and rebuilding followed a 1971 UNESCO report that pointed to damage caused by environmental pollution & errors made by restorers, particularly corrosion, expansion & contraction of the iron clamps that was discolouring and cracking the stone.

The restoration programme by architects Demosthenes Giraud & Kostas Mamaloungas received initial approval in 1994, & in 1998 the work of dismantling and rebuilding the temple for the third time began under the direction of Kostas Mamaloungas and civil engineer D. Michalopoulou.

In 2000 dismantling work began, including removing 315 marble sections. Balanos' concrete cella floor was removed and replaced by a stainless steel grid, while other concrete additions were replaced with marble. Clamps of titanium were used in the place of iron.

Finally, the work was finished; the scaffolding around the temple was removed in September 2010. The Temple of Athena Nike now stands one metre taller than it did before the previous restoration.

elginism.com/acropolis/the-…

elginism.com/acropolis/the-…

There is now a large void below the temple and it's steel support beams - the remains of earlier temples can be seen within this void and they can be studied without needing to remove the temple above.

Hopefully this will have been the last dismantling of the temple for a long while - although I imagine that this was what they thought the previous two times that the temple was rebuilt too.

Some time after the temple was completed, around 410 BC a parapet was added around it to prevent people from falling from the steep bastion. The outside of the parapet was adorned by carved relief sculptures showing Nike in a variety of activities and all in procession.

This parapet is quite unusual, in that there is relatively little low level sculptural decoration on the Acropolis, most of it being above column height.

Within the parapet is a stairway, leading up from the Propylaeum stairs.

Within the parapet is a stairway, leading up from the Propylaeum stairs.

https://twitter.com/elginism/status/1573016449979150336

On the parapet, there would have stood a famous marble statue of a wingless Nike. The positioning of this statue has Nike leaning towards her right foot with her right arm stretching towards her sandal and her clothes slipping off her shoulder.

The famous parapet of Nike removing her sandal is an example of Wet drapery. Wet drapery involves showing the form of the body but also concealing the body with the drapery of the clothing. Not an easy effect to achieve when carving marble.

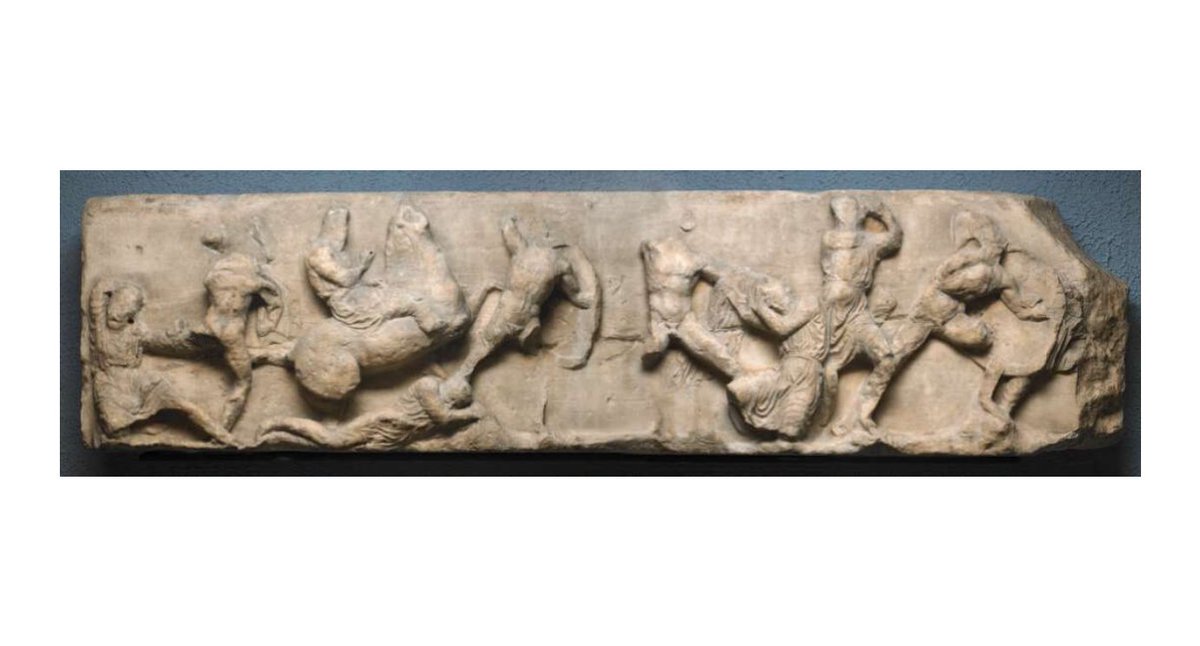

The friezes of the building's entablature were decorated on all sides with relief sculpture in the idealized classical style of the 5th century BC. The orientation of the temple is set up so that the East Frieze sits above the entrance of the temple on the porch side.

As previously alluded to, there are a fair few bits from the temple of Athena Nike that were removed from the site by Lord Elgin and are now in the British Museum.

britishmuseum.org/collection/obj…

britishmuseum.org/collection/obj…

Although these pieces could have been included in the restored building or exhibited in the Acropolis Museum, the British Museum will not return them, despite the fact that most are not currently on public display.

britishmuseum.org/collection/obj…

britishmuseum.org/collection/obj…

The British Museum also holds various drawings of the building by Feodor Iwanowitsch Kalmück.

britishmuseum.org/collection/obj…

britishmuseum.org/collection/obj…

Although the Italian painter Giovanni Battista Lusieri is the best known artist in Elgin's delegation to Athens, 5 other artists traveled there with him, including Feodor - an ethnic Mongolian engraver who had grown up in Russia.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feodor_Iw…

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feodor_Iw…

The most significant pieces that Elgin removed from the Athena Nike temple are 4 frieze panels.

britishmuseum.org/collection/obj…

britishmuseum.org/collection/obj…

These panels are currently displayed in room 19 - the Greek gallery that also houses the Caryatid removed by Elgin.

britishmuseum.org/collection/obj…

britishmuseum.org/collection/obj…

Good luck is required however if you want to visit this gallery. The last few times I've been to the British Museum it has been closed to the public.

britishmuseum.org/collection/obj…

britishmuseum.org/collection/obj…

Although part of the Elgin Collection in the British Museum, these four panels are not part of Greece's current request which relates only to the sculptures from the Parthenon. As with the one Caryatid though, there is a strong argument for their return.

britishmuseum.org/collection/obj…

britishmuseum.org/collection/obj…

This photo gives a good overview of the temple of Athena Nike (middle right side of image) as it exists today - and it's relationship to the rest of the buildings on the Acropolis.

https://mobile.twitter.com/tzoumio/status/1569956976913797121

I guess a key part of the above story is that what we see as permanent is not necessarily quite as immovable as we might think. The Acropolis has evolved a lot over time, to reach its current form and this has involved a lot of dismantling prior to rebuilding.

Many earlier repairs had problems - because of the limited nature of the works and because of how the works were carried out.

Recent restoration works have made far more effort to ensure pieces go back int he correct places - not just where they seem to fit.

Recent restoration works have made far more effort to ensure pieces go back int he correct places - not just where they seem to fit.

With the exception of the Caryatid, the fact that Elgin's collection included a lot more than just the Parthenon Sculptures is something that is often forgotten - but all of this collection was acquired in similarly controversial circumstances.

It is helpful that some sketches from Elgin's interventions on the Acropolis survive - most of Luiseri's work was lost off Crete in the wreck of the Cambria.

The timing of the first restoration of the temple means it is likely that the pieces from this building fell within the terms of Elgin's firman (or permit) - it's references to items lying on the ground. Of course, this doesn't alter the overwhelming moral case for their return.

Finally, to go back to the idea of how permanence is sometimes illusory - perhaps it's a good time to reflect on how the Elgin Collection in the British Museum is perhaps not as permanent as it first appears.

If a temple can disappear & reappear, then some sculptures can return.

If a temple can disappear & reappear, then some sculptures can return.

Came across this photo taken after the first reconstruction of the temple.

There are quite a few differences from how it looks now (as you'd expect).

There are quite a few differences from how it looks now (as you'd expect).

https://twitter.com/tzoumio/status/1552546192759951361?t=0PShkDHeVU4l3YDzEf0UxQ&s=19

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh