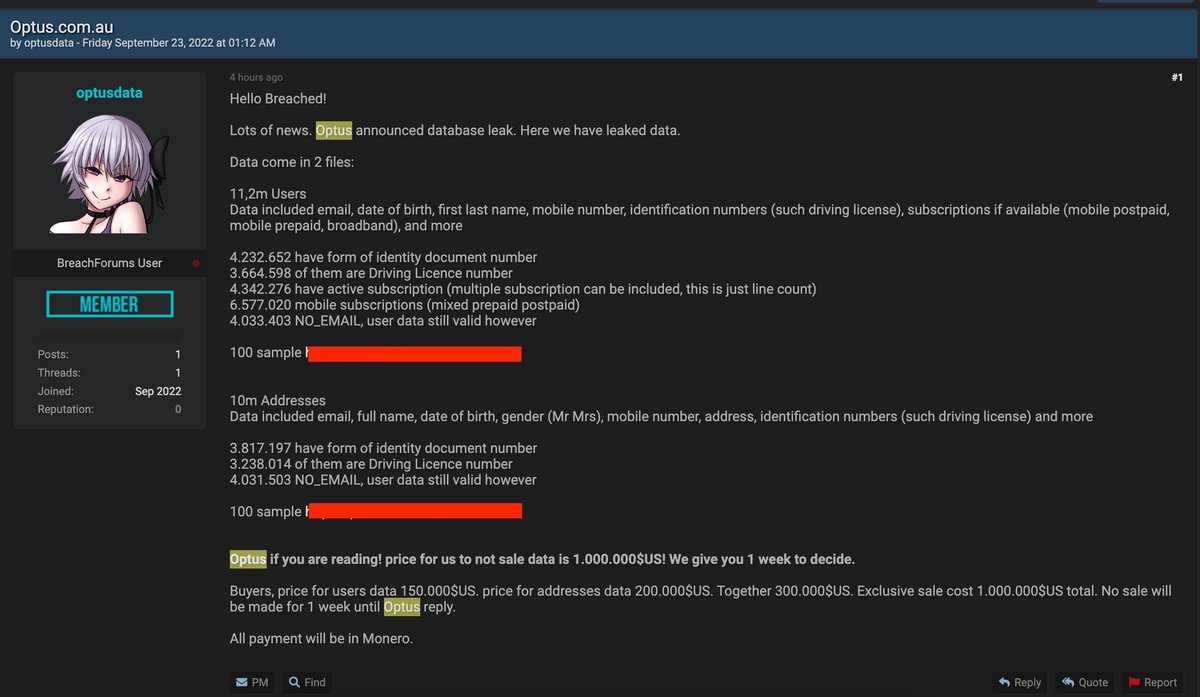

Here are some technical observations related to the Optus breach. This gets into the technical weeds, but it’s important for understanding how this breach may have happened. I’ll try to make it as comprehensible as possible. #optushack #auspol #infosec

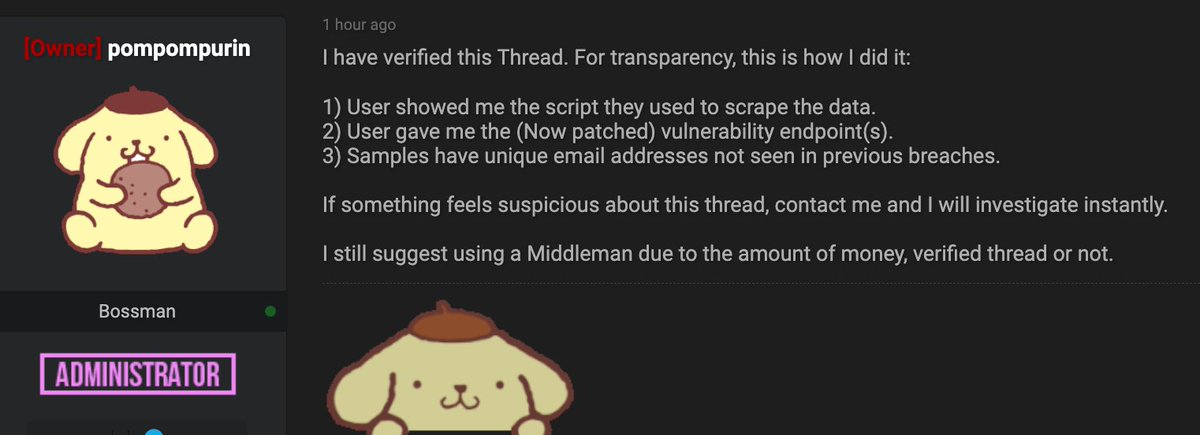

Some information is based on public data. The analysis comes from information security experts, whom I appreciate reaching out to me. 😉

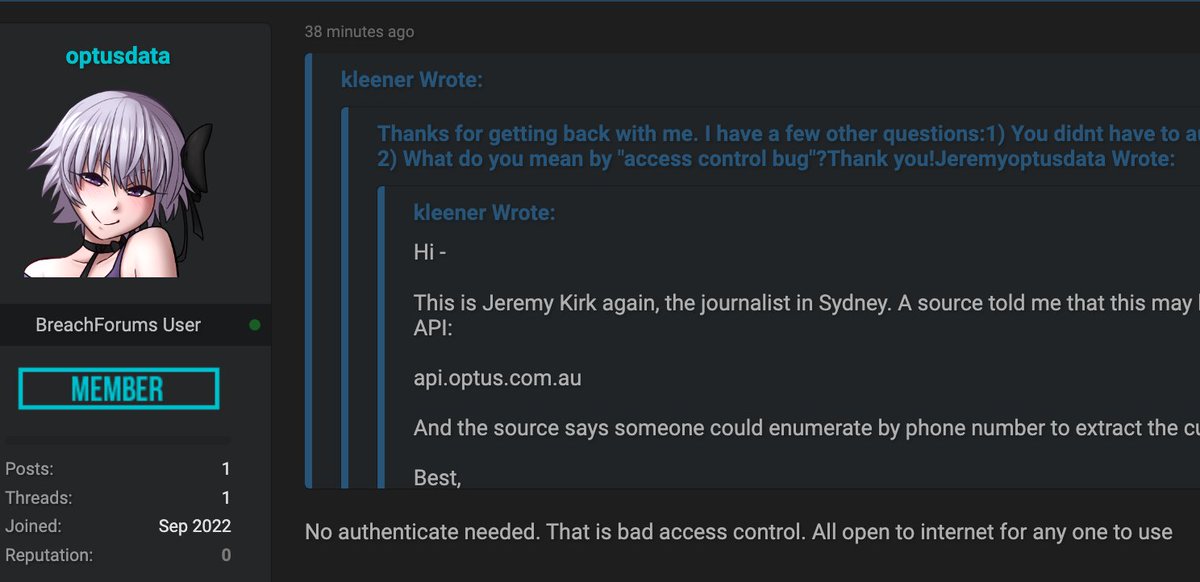

We know that the breach occurred because the Optus hacker abused an application programming interface (API) which was api[dot]optus.com.au. As we know, that API was left open on the internet.

You didn’t have to login into it, and it was connected to Optus’ huge customer database. api[dot]optus.com.au appeared in public Domain Name System (DNS) records on June 19.

The DNS is the lookup system that translates domain names, such as “example.com,” into an IP addresses that can then be accessed by another computer across the internet.

So api[dot]optus.com.au, which is the address of the API, becomes live on the internet on June 19. On Sept. 19 – just around two days before Optus detected the breach – the API was then “onboarded” to Akamai. #infosec #OptusHack

This means that any traffic that goes to the API first goes through Akamai. The domain name becomes api[dot]optus.com.au.edgekey.net. See here: dnshistory.org/dns-records/ap…

Akamai makes web application firewalls, or WAFs. WAFs are security tools that filter out attacks coming from the internet. WAFs are an important defence for applications, APIs, etc. Akamai also has an API gateway, a security tool for authorisation, traffic control, etc.

The question that this information raises is: Was that Optus API protected by anything in the three months prior to it moving to Akamai? We know the API was hosted in Google Cloud/Apigee, which does offer an open-source WAF. Was that it use? #OptusDataBreach

As further background, people have told me that when setting up APIs, security controls are usually applied last. The reason is that if anything is functionally wrong, it’s easier to troubleshoot it without the security controls on top. #OptusDataBreach

But that testing should always be done a test network and with a dummy database that contains mock and not real customer data. To put it another way, developers shouldn’t use full production data – like a real customer database – in testing an API. #OptusHack #auspol

ENDING CAVEAT: We don’t know if this is what happened at Optus, but generally is a security issue that has cause problems in the past. Only Optus has the full story on this, and hopefully we will learn it soon.

Everyone: Corrections, comments welcomed on the thread.

Correction from me. Twitter removed the "www" when I wrote the API endpoint in the way I did earlier in the thread. To clarify, it is api [dot] www [dot] optus [dot] com [dot] au

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh