In my speech “Finding the right mix: monetary-fiscal interaction at times of high inflation” at the Bank of England Watchers’ conference I explained why I see a risk that monetary and fiscal policies are pulling in opposite directions, leading to a suboptimal policy mix. 1/19

https://twitter.com/ecb/status/1595764981890424832

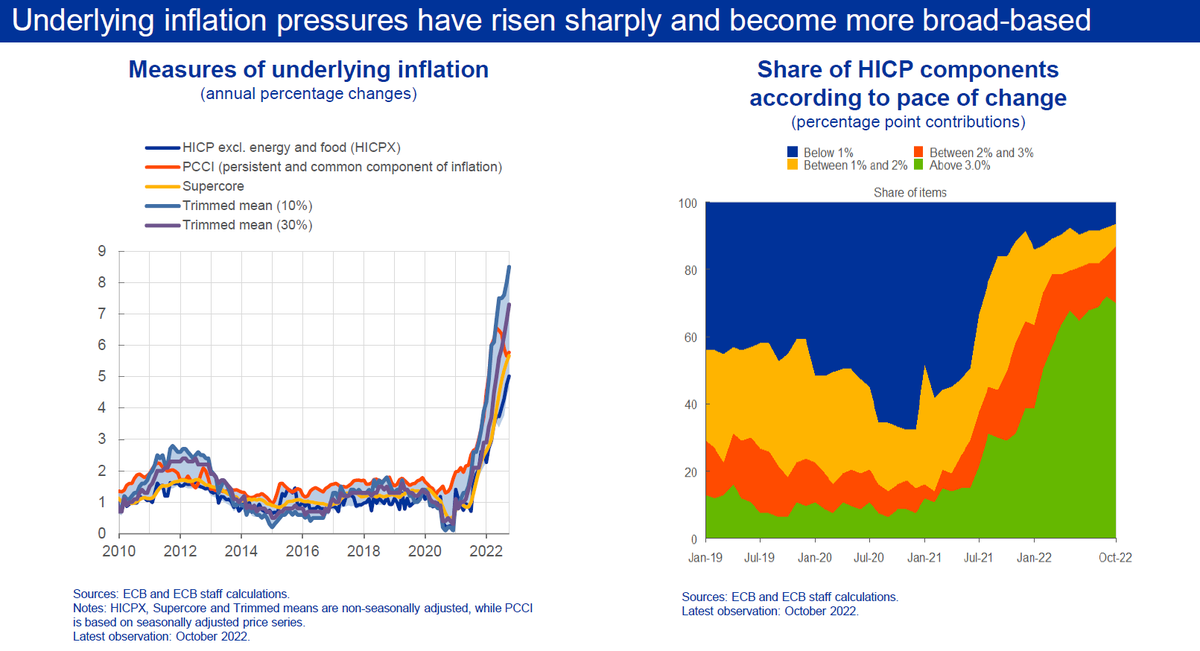

In the recovery from the pandemic, demand started to outpace supply, putting upward pressure on prices. This was reinforced by a surge in energy and food prices after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Inflation broadened substantially, pushing up underlying inflation. 2/19

These price pressures are unlikely to dissipate quickly. Accumulated excess savings remain significant in both nominal and real terms. Firms in the manufacturing sector continue to have full order books. Unemployment rates remain at record low levels. 3/19

Moreover, the pandemic and the energy crisis may have more permanent negative effects on potential output. Potential output growth is constrained by labour scarcity. The pandemic has led to lower labour participation in sectors where it is hard to work from home. 4/19

The energy crisis has hit investment and total factor productivity, especially in energy-intensive sectors. In the car industry the increase in energy costs has become the most important factor holding back production. Demand-side factors continue to be supportive. 5/19

ECB staff analysis shows that a persistent increase in energy prices significantly and persistently lowers potential output across euro area countries. 6/19

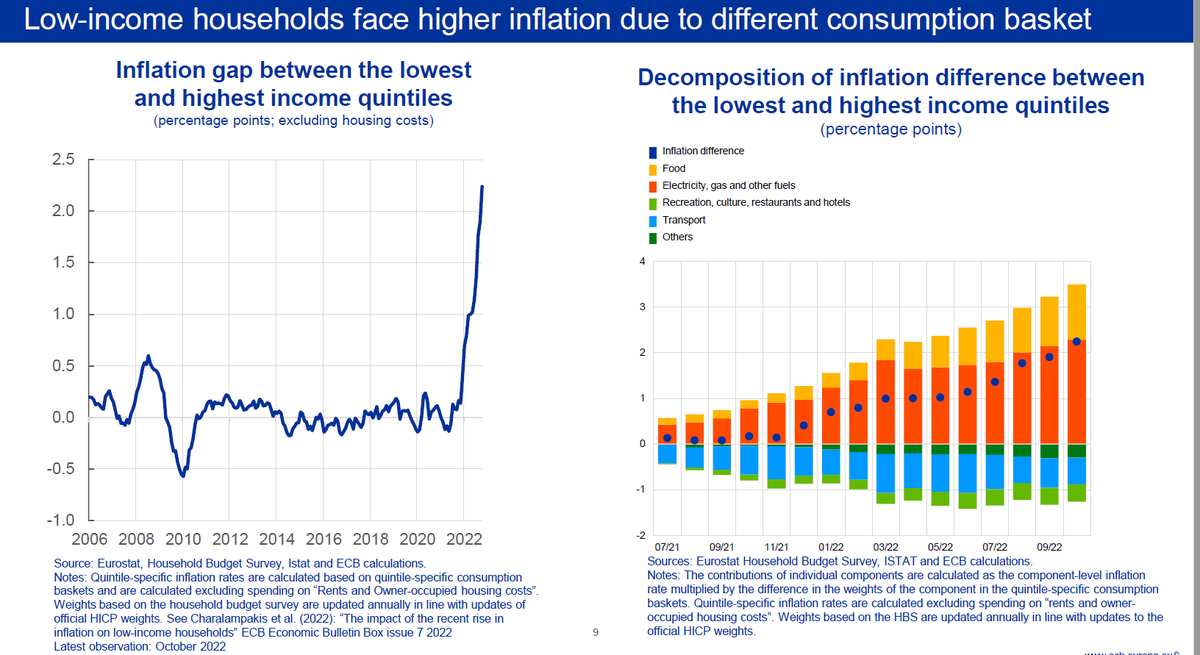

In the current environment, monetary and fiscal policies should pull together. Fiscal policy needs to protect the most vulnerable households and firms in a targeted way. Low-income households face much higher effective inflation rates due to a different consumption basket. 7/19

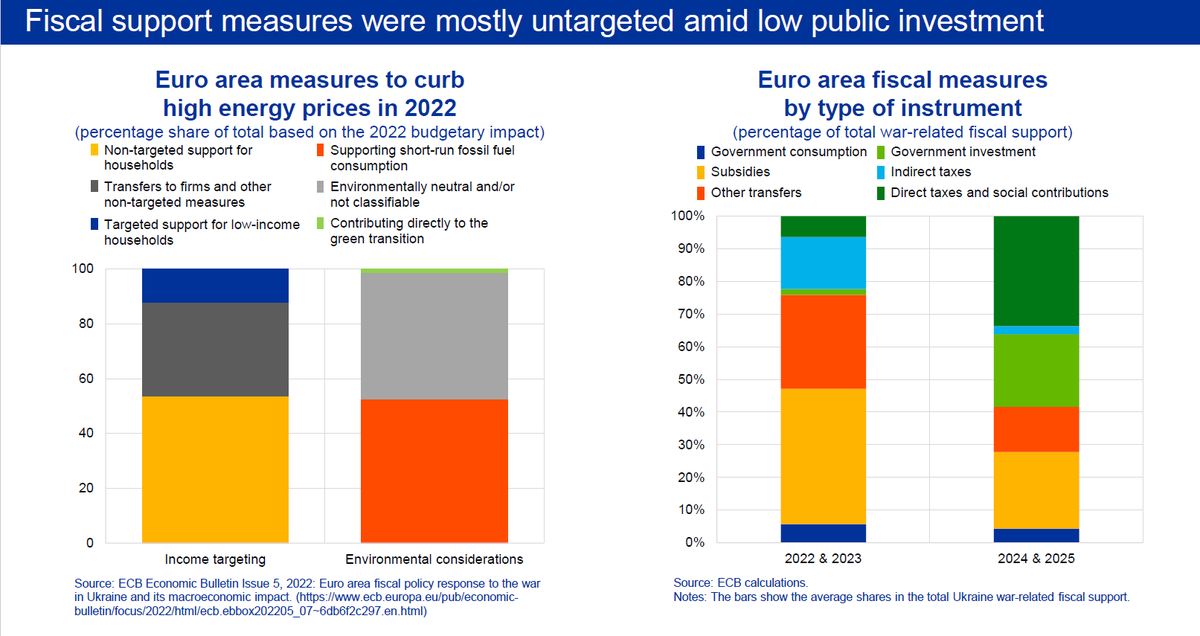

Governments should also foster potential growth and energy independence through public investment and structural reforms, addressing the underlying sources of the supply-side shocks. This would also help to dampen inflationary pressure over the medium term. 8/19

Unfortunately, governments have often not followed these prescriptions. Few measures target low-income households. Only 1 % contribute directly to the green transition. Public investment will remain subdued, picking up only in 2024/25, mainly due to defence spending. 9/19

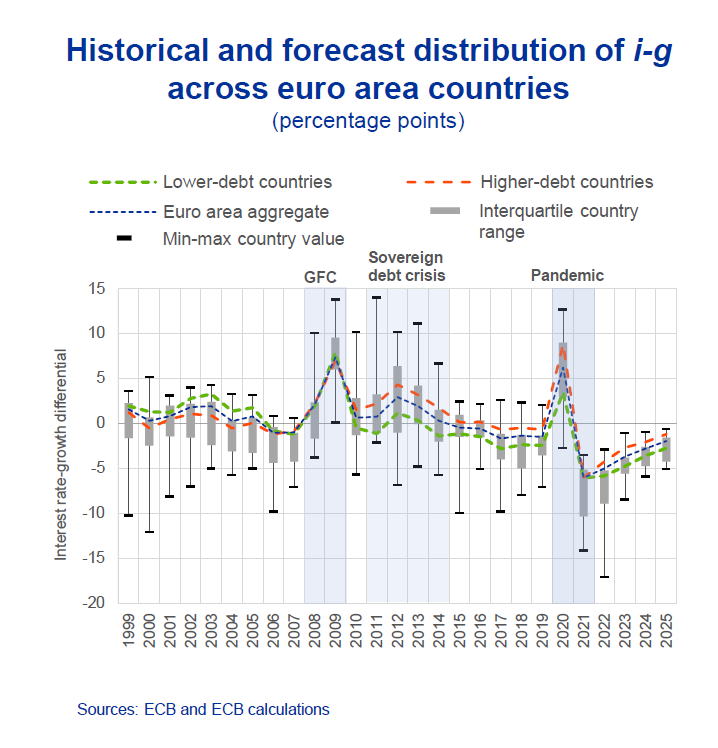

Sound fiscal policies are also a key factor for stabilising debt dynamics. Initially, higher inflation had a beneficial effect on debt-to-GDP ratios. However, an inflation increase due to a supply-side shock is unlikely to alleviate the debt burden over the medium term. 10/19

Rising interest rates due to tighter monetary policy or higher public debt lift up the interest rate-growth differential. Currently, the differential still stands near historic lows, but it is about to become less favourable. 11/19

If governments do not credibly commit to sound fiscal policy, people may expect that higher inflation needs to ensure debt sustainability. With a credible central bank, monetary dominance prevails and monetary policy will tighten more if fiscal policy is too accommodative. 12/19

Fiscal policy is at risk of contributing to inflation at a time when price pressures remain unabated. Euro area inflation has continued to surprise on the upside. While fears of a technical recession have increased, economic data have recently also surprised positively. 13/19

Monetary policy must restore price stability as quickly as possible. ECB policy has already led to a tightening of financing conditions, but real rates mostly remain negative. Markets’ expectations of a “pivot” have worked against efforts to withdraw accommodation. 14/19

The longer inflation remains high, the larger the risk that inflation expectations de-anchor, putting medium-term price stability at risk. Higher perceived inflation appears to have a substantial impact on households’ inflation expectations, and this impact has been rising. 15/19

The largest risk for central banks remains a policy that is falsely calibrated on the assumption that inflation declines quickly, underestimating inflation persistence. #JacksonHole Therefore, we need to raise interest rates further, probably into restrictive territory. 16/19

Incoming data so far suggest that the room for slowing down the pace of interest rate hikes remains limited. High uncertainty around neutral rate estimates implies that they cannot serve as yardstick for our interest rate adjustments. Policy needs to remain data dependent. 17/19

Interest rates are the main instrument for calibrating our monetary policy stance, but we will also normalise our balance sheet in a measured and predictable way. We continue to stand ready to counter fragmentation in financial markets not justified by economic fundamentals.18/19

Summing up, governments need to internalise the effects of their actions on future inflation and monetary policy. Monetary policy needs to ensure a timely return of inflation to target, preserving people’s purchasing power and supporting investment by reducing uncertainty. 19/19

P.S.: Thanks to all my colleagues @ecb who commented on the speech.

The slides are found here: ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date…

The slides are found here: ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh