Talking about hyponatremia is so stereotypically internal medicine and is, quite frankly, something I used to loathe.

Here's a simplified approach to hyponatremia in the inpatient setting, along with some key clinical pearls.

- Thread -

#MedEd #MedTwitter #FOAMed #POCM

1/25

Here's a simplified approach to hyponatremia in the inpatient setting, along with some key clinical pearls.

- Thread -

#MedEd #MedTwitter #FOAMed #POCM

1/25

Use this @pointofcaremed template to help you master the topic!

pointofcaremedicine.com/nephrology/hyp…

And check out the podcast and YouTube video to go with it!

anchor.fm/pointofcarepod…

2/25

pointofcaremedicine.com/nephrology/hyp…

And check out the podcast and YouTube video to go with it!

anchor.fm/pointofcarepod…

2/25

Hyponatremia is due to a relative excess of water to sodium in the extracellular space.

It is more commonly caused by excess water than depleted sodium.

Working up hyponatremia comes down to determining why there is excess water and if it's an "appropriate" response.

3/25

It is more commonly caused by excess water than depleted sodium.

Working up hyponatremia comes down to determining why there is excess water and if it's an "appropriate" response.

3/25

The hypothalamus responds to tonicity, not volume.

If you are hypertonic, your brain makes you thirsty and releases ADH so your kidneys hold on to more free water.

Sodium drives almost all of the tonicity.

Remember the serum osm equation:

= 2*Na + BUN/2.8 + glucose/18

4/25

If you are hypertonic, your brain makes you thirsty and releases ADH so your kidneys hold on to more free water.

Sodium drives almost all of the tonicity.

Remember the serum osm equation:

= 2*Na + BUN/2.8 + glucose/18

4/25

Tonicity is important clinically because it impacts fluid shifts and thus cell size.

Too much water leads to swelling; too little leads to shrinking.

The rapid changes in cell size and the consequent damage can lead to clinical manifestations, most critically in the CNS.

5/25

Too much water leads to swelling; too little leads to shrinking.

The rapid changes in cell size and the consequent damage can lead to clinical manifestations, most critically in the CNS.

5/25

30% of patients in the hospital will have hyponatremia, yet most cases are mild and clinically irrelevant.

While the ddx is broad, in reality, most inpatient presentations are due to hypovolemia, decreased effective circulating volume (3rd spacing), ESRD, or SIADH.

6/25

While the ddx is broad, in reality, most inpatient presentations are due to hypovolemia, decreased effective circulating volume (3rd spacing), ESRD, or SIADH.

6/25

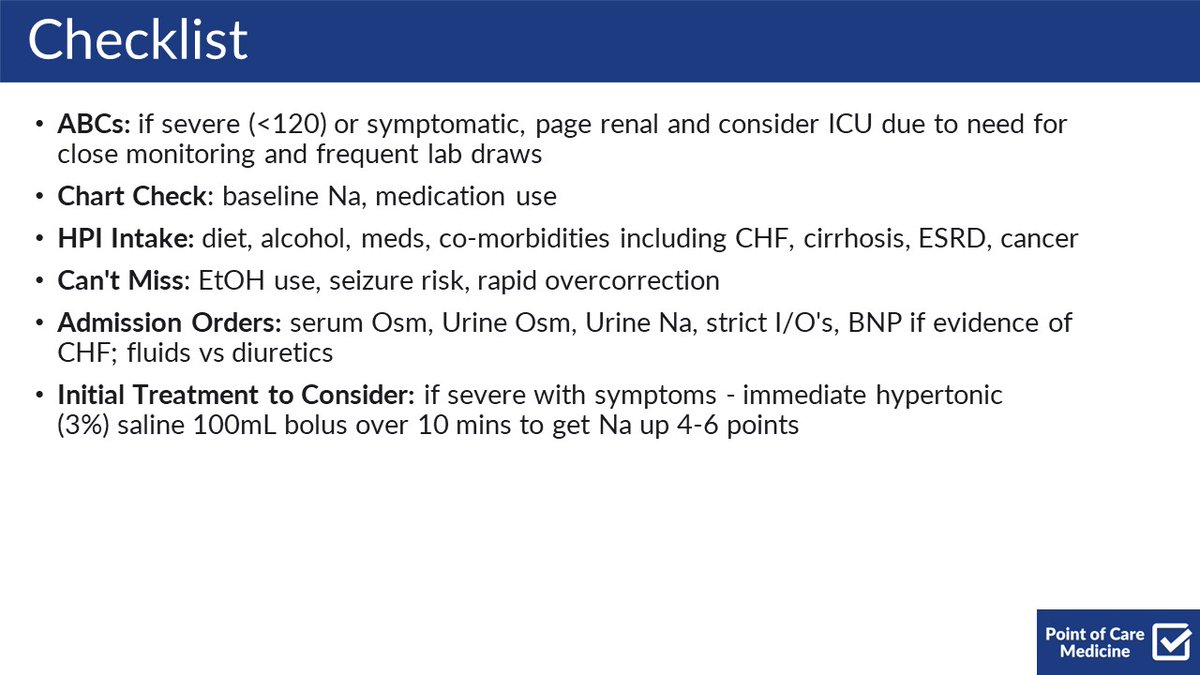

To work up the etiology of hyponatremia, you'll need:

- Serum Osm (SOsm)

- Urine Osm (UOsm)

- Urine Sodium (UNa)

Here's a checklist of other things to consider when admitting patients with hyponatremia.

7/25

- Serum Osm (SOsm)

- Urine Osm (UOsm)

- Urine Sodium (UNa)

Here's a checklist of other things to consider when admitting patients with hyponatremia.

7/25

Here's a framework for approaching common causes of inpatient hyponatremia.

First, confirm it's hypotonic hyponatremia (SOsm <300)

Next, determine if ADH is driving the process (UOsm >100)

Finally, determine if RAAS is on (UNa <30)

8/25

First, confirm it's hypotonic hyponatremia (SOsm <300)

Next, determine if ADH is driving the process (UOsm >100)

Finally, determine if RAAS is on (UNa <30)

8/25

Other frameworks historically used volume status as key branch points.

However, this paper suggests the above framework may be better due to objective lab values rather than relying on the subjective, notoriously difficult volume assessment.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20609688/

9/25

However, this paper suggests the above framework may be better due to objective lab values rather than relying on the subjective, notoriously difficult volume assessment.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20609688/

9/25

Pseudohyponatremia is an error caused by too much protein or lipid in the blood, based on the way the lab measures serum sodium indirectly.

In these cases, the patient's sodium level is actually normal.

10/25

In these cases, the patient's sodium level is actually normal.

10/25

True hypertonic hyponatremia is most commonly due to the presence of osmotically active glucose, which leads to actual fluid shifts.

We correct for hyperglycemia to know what the sodium would be if glucose was normal, but it's still true hyponatremia

11/25

We correct for hyperglycemia to know what the sodium would be if glucose was normal, but it's still true hyponatremia

11/25

ADH acts on the collecting ducts and leads to the absorption of free water.

ADH will be the driver of most inpatient hyponatremia.

If not, it's due to those zebras - drinking way too much water, getting way too little solute from one's diet, or a combination of both.

12/25

ADH will be the driver of most inpatient hyponatremia.

If not, it's due to those zebras - drinking way too much water, getting way too little solute from one's diet, or a combination of both.

12/25

If driven by ADH, the question becomes - is the body releasing ADH appropriately?

If hypovolemic or decreased effective volume, the body should try to hold on to water by activating RAAS and trying to also hold on to sodium.

In this case, ADH is "appropriate"

13/25

If hypovolemic or decreased effective volume, the body should try to hold on to water by activating RAAS and trying to also hold on to sodium.

In this case, ADH is "appropriate"

13/25

If the body has not turned on RAAS, then the ADH release is not appropriate.

This is most commonly due to SIADH.

It can also be due to diuretics (which work by preventing the body from reabsorbing sodium and counteracting natural RAAS), ESRD, AI, and hypothyroidism.

14/25

This is most commonly due to SIADH.

It can also be due to diuretics (which work by preventing the body from reabsorbing sodium and counteracting natural RAAS), ESRD, AI, and hypothyroidism.

14/25

SIADH is commonly caused by:

- Pneumonia

- Malignancy (classically ectopic ADH from small cell lung cancer)

- Meds - SSRIs and AEDs

- Primary Brain Lesions

15/25

- Pneumonia

- Malignancy (classically ectopic ADH from small cell lung cancer)

- Meds - SSRIs and AEDs

- Primary Brain Lesions

15/25

Treatment depends on the severity and etiology.

If severe (Na <120) or symptomatic (seizure, AMS, N/V, weakness) hypertonic 3% NS can be bolused to get the patient out of the life-threatening range without rapid overcorrection.

Renal consultants should be involved.

16/25

If severe (Na <120) or symptomatic (seizure, AMS, N/V, weakness) hypertonic 3% NS can be bolused to get the patient out of the life-threatening range without rapid overcorrection.

Renal consultants should be involved.

16/25

If ADH is absent (i.e 2/2 primary polydipsia, beer potomania, tea + toast, etc), restrict fluids and slowly introduce solute.

Treating this bucket of etiologies has the highest likelihood of overcorrection.

17/25

Treating this bucket of etiologies has the highest likelihood of overcorrection.

17/25

If ADH is on and RAAS is active, replete with fluids (hypovolemia) OR diurese if overloaded (3rd spacing 2/2 CHF, cirrhosis, nephrotic syndrome).

If ADH is on and RAAS is off, fluid restrict ~1L/day and give salt tabs. Lasix and vaptans may also be effective.

18/25

If ADH is on and RAAS is off, fluid restrict ~1L/day and give salt tabs. Lasix and vaptans may also be effective.

18/25

Some helpful management pearls:

You should NEVER bolus free water via IV. If you do, consult renal and give hypertonic fluid to even things out and prevent rapid changes.

Repleting potassium is essentially giving sodium since they are freely exchanged, so be cautious.

19/25

You should NEVER bolus free water via IV. If you do, consult renal and give hypertonic fluid to even things out and prevent rapid changes.

Repleting potassium is essentially giving sodium since they are freely exchanged, so be cautious.

19/25

Osmotic demyelination syndrome (ODS) is the feared complication of overcorrection since it can lead to locked-in syndrome.

Overall, the risk of this is very low.

Factors that increase risk include:

- starting Na <105

- chronic malnutrition

- chronic EtOH use

20/25

Overall, the risk of this is very low.

Factors that increase risk include:

- starting Na <105

- chronic malnutrition

- chronic EtOH use

20/25

Some notes on urine studies:

A shortcut to approximate UOsm is to multiply the last two digits of the serum gravity seen on UA by 30.

Also important to recognize that ESRD and diuretic use limits the interpretation of UOsm and UNa

21/25

A shortcut to approximate UOsm is to multiply the last two digits of the serum gravity seen on UA by 30.

Also important to recognize that ESRD and diuretic use limits the interpretation of UOsm and UNa

21/25

If you remember nothing else:

- Most hyponatremia is incidental and clinically insignificant

- Represents excess water compared to sodium

- Most common - hypovolemia, 3rd spacing, SIADH, ESRD

- SOsm <300 hypotonic, UOsm >100 ADH present, UNa <30 RAAS active

22/25

- Most hyponatremia is incidental and clinically insignificant

- Represents excess water compared to sodium

- Most common - hypovolemia, 3rd spacing, SIADH, ESRD

- SOsm <300 hypotonic, UOsm >100 ADH present, UNa <30 RAAS active

22/25

Shoutout to @COREIMpodcast - their articles and podcasts are the only reason I have as much as a tenuous grasp on the topic of hyponatremia.

Absolutely changed the game.

coreimpodcast.com/2021/02/10/5-p…

23/25

Absolutely changed the game.

coreimpodcast.com/2021/02/10/5-p…

23/25

This graphic from @RahulM_MD is iconic.

Props

24/25

Props

https://twitter.com/RahulM_MD/status/1600496618423427082

24/25

The @CPSolvers Dx Schema is great if you are lost or out hunting zebras.

clinicalproblemsolving.com/dx-schema-hypo…

25/25

clinicalproblemsolving.com/dx-schema-hypo…

25/25

As always, calling on my fellow MedEd Twitter addicts - what would you add?

@ASanchez_PS

@MadellenaC

@Mark_Heslin

@bharatbalan

@lukasronnerMD

@EdanZitelny

@ASanchez_PS

@MadellenaC

@Mark_Heslin

@bharatbalan

@lukasronnerMD

@EdanZitelny

I hope you've found this thread helpful.

Follow me @ROKeefeMD for more.

Like/Retweet the first tweet below if you can:

Follow me @ROKeefeMD for more.

Like/Retweet the first tweet below if you can:

https://twitter.com/ROKeefeMD/status/1625178059891675137

You can read the unrolled version of this thread here: typefully.com/ROKeefeMD/EqKK…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh