***New paper*** How do affirmative action's most common race-neutral alternatives comparatively reshape universities' enrollment of underrepresented minority (URM) and lower-income students?

Here's a thread of new evidence from California. #EconTwitter

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

Here's a thread of new evidence from California. #EconTwitter

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

My own prior work has shown that affirmative action provided big admission advantages to URM Californians before the state banned AA in 1998.

The ban led URM students to cascade into less-selective universities, which had long-run economic consequences: academic.oup.com/qje/advance-ar…

The ban led URM students to cascade into less-selective universities, which had long-run economic consequences: academic.oup.com/qje/advance-ar…

The new study starts by taking a look at admission and enrollment at the University of California since the 1990s.

While URM enrollment seems to has "recovered" at Berkeley and UCLA since AA was banned, the recovery can be wholly explained by demographic trends in California.

While URM enrollment seems to has "recovered" at Berkeley and UCLA since AA was banned, the recovery can be wholly explained by demographic trends in California.

Under #affirmativeaction, Black and Hispanic students were twice as likely to be admitted to Berkeley/UCLA as white and Asian students with similar SATs and grades.

That advantage fell to 40% in 1998, and the policies implemented since then haven't moved the needle so much.

That advantage fell to 40% in 1998, and the policies implemented since then haven't moved the needle so much.

Enrollment of lower-income students grew in the 2000s at the less-selective and selective UC campuses, but has stagnated for the past 15 years. UC's access-oriented admission policies have not meaningfully shifted campuses' socioeconomic composition.

Now let's do a deeper dive into each of the admission policies UC has implemented to target disadvantaged students since the 1990s. What do these policies do?

For reference, affirmative action increased URM UC enrollment by at least 20 percent, and 60 percent at Berkeley/UCLA.

For reference, affirmative action increased URM UC enrollment by at least 20 percent, and 60 percent at Berkeley/UCLA.

In 2001, UC implemented Eligibility in the Local Context, a top percent policy. ELC guaranteed UC admission to the top 4% of grads from each CA high school.

The policy provided admissions advantages to eligible students at 4 campuses: Irvine, San Diego, Davis, and Santa Barbara.

The policy provided admissions advantages to eligible students at 4 campuses: Irvine, San Diego, Davis, and Santa Barbara.

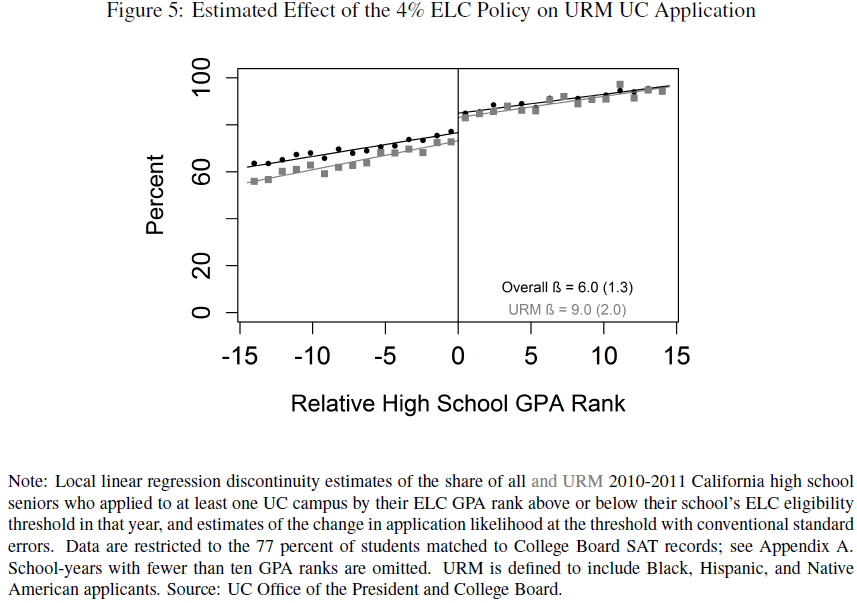

ELC affected UC enrollment in two ways. First, about 150 URM students per year enrolled at UC as a result of their being admitted to selective UC campuses through the ELC program.

ELC also increased URM enrollment by informing high school graduates of their ELC eligibility even before they applied to UC. This led to increased applications from URM students.

About 170 additional URM students enrolled at UC each year through this "application channel".

About 170 additional URM students enrolled at UC each year through this "application channel".

The "application channel" is important to keep in mind when it comes to admissions policies.

Application behavior explained one-third of the URM enrollment effect of affirmative action and half the effect of top percent policies (as long as kids know whether they're eligible!).

Application behavior explained one-third of the URM enrollment effect of affirmative action and half the effect of top percent policies (as long as kids know whether they're eligible!).

In total, the 2001-2011 ELC policy increased URM enrollment at participating UC campuses like Irvine by around 6 percent, and increased overall URM UC enrollment by about 3 percent.

Remember the point of comparison: affirmative action increased URM enrollment by 20 percent.

Remember the point of comparison: affirmative action increased URM enrollment by 20 percent.

UC "expanded" its top percent policy to the top 9% of students from each high school in 2012. But most campuses reneged from participating!

So the policy went from "4% can go to Davis or Irvine" to "9% can go to Merced", the least-selective UC campus. Take-up is now negligible.

So the policy went from "4% can go to Davis or Irvine" to "9% can go to Merced", the least-selective UC campus. Take-up is now negligible.

The other major access-oriented admissions policy implemented by UC campuses is holistic review, in which "a trained evaluator or set of evaluators craft a single score for the applicant based upon a combination of the criteria," like at many private universities.

Six UC campuses have adopted holistic review since 2002. Each time, URM applicants have each become about 2 percentage points more likely to be admitted to that campus.

In total, holistic review increases URM enrollment at implementing campuses by about 7 percent.

In total, holistic review increases URM enrollment at implementing campuses by about 7 percent.

Top percent policies had even smaller effects on lower-income students' UC enrollment than on URM enrollment. Holistic review, if anything, seems to slightly decrease lower-income students' admission chances.

So neither seems to do much in terms of socioeconomic diversity.

So neither seems to do much in terms of socioeconomic diversity.

What does this all mean for universities interested in maintaining racial diversity without explicit race-based affirmative action policies? California provides two key lessons.

First, despite strong policy interest in promoting URM UC enrollment, the policies UC has implemented have hardly moved the needle on URM enrollment since affirmative action was banned in 1998.

This is a cautionary tale for schools hoping for easy race-neutral AA alternatives.

This is a cautionary tale for schools hoping for easy race-neutral AA alternatives.

The policies also haven't done much to promote socioeconomic diversity, another policy goal that has traditionally been more difficult to measure using available data.

But second, my and others' work has shown that access-oriented admissions policies tend to be efficiency-enhancing. Lower-testing students tend to get more out of selective universities than their higher-testing peers.

https://twitter.com/zbleemer/status/1341089166587813888

This is a call for experimentation! The costs of trying new policies to admit more disadvantaged students are low.

Schools around the US will probably be driven to all sorts of different policies in the coming years, and that might prove beneficial to all of us in the long run.

Schools around the US will probably be driven to all sorts of different policies in the coming years, and that might prove beneficial to all of us in the long run.

Thanks for reading! Once again, the full paper is here: sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

Stay tuned for more work on the efficiency and equity implications of feasible access-oriented college admissions policies!

Stay tuned for more work on the efficiency and equity implications of feasible access-oriented college admissions policies!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh