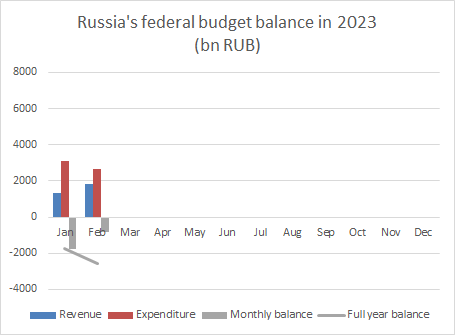

1) New data on Russia's federal #budget in February is out. Some normalization after a high January deficit was expected, but the opposite happened. The deficit grew to 2.6 tn RUB, 1.7% of GDP after two months. Revenues in February 2023 were 1.8 tn RUB, expenditure 2.6 tn RUB.

2) Last year around this time, the Russian budget was firmly in positive territory. The January 2023 deficit was clearly not representative, but an additional deficit of 800 billion RUB in February shows it's not a one-off phenomenon.

3) On the revenue side, the problem for Russia's finance ministry are the very small oil and gas revenues. This will slightly improve in the coming months, as Russia will adopt a new formula to calculate taxes (based on a higher assumed oil price).

4) On the expenditures side, the war is forcing the government to pay upfront for weapons. This is supposed to lead to lower spending in December, but I believe that when I see it. Overall, it still looks like spending will be significantly higher than planned.

5) Important to take into account strong fluctuations month-to-month in Russia's budget, which happen for different reasons (seasonality, tax rules, one-off payments etc.). But based on today's data, Russia's government will need to borrow a lot more than planned for this year.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh