The @usnews rankings are always questionable at best, but this year's newly released version, which rank #publichealth sub-disciplines, is particularly egregious. Time for a 🧵.

For the first time, the rankings include not only an overall ranking of schools of public health, but also of disciplines within public health including biostatistics, epidemiology, environmental health, health policy, and social/behavioral sciences.

Sounds great, right? Except instead of being ranked by, you know, experts within each of these disciplines, the rankings were done primarily by deans and "other academics".

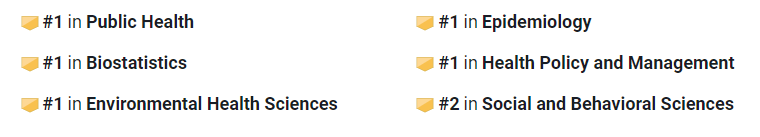

The upshot (or downshot, depending on your view) is that each subdiscipline's rankings are nearly a perfect match for the overall public health rankings, a level of uniformity across specialty areas that defies common sense. Some examples:

Pitt (side travesty: @pittbiostat, a well-established department, isn't even ranked!)

There's more ridiculousness when you dig into biostatistics, which was ranked by actual experts (department chairs) last year. The decision to rank biostat as a pub hlth "sub-discipline" this year means great programs based in a med school, like @UPennDBEI, barely make the list.

You know something is very wrong when the correlation between the program rankings of biostat and environmental health programs this year is (much) higher than the correlation between last year's and this year's biostat rankings.

Yes, rankings aren't everything, but they are an important entry point for students considering graduate study in public health, especially for students at smaller colleges without an academic public health footprint.

When we erase the distinctions between the various sub-specialties within public health by basing rankings on the opinions of those without specialty knowledge, we do a disservice not only to the programs themselves but also to those students.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter