Here is the explanation of the ‘homo economicus’ test!

The opportunity for a thread about what economists mean with the notion of economic ‘rationality’.

First, the test results:

(Thread)

The opportunity for a thread about what economists mean with the notion of economic ‘rationality’.

First, the test results:

https://twitter.com/page_eco/status/1177178854470742016?s=20

https://twitter.com/page_eco/status/1177179035920527360?s=20

(Thread)

Many seem to have interpreted it as a test of the ability to maximise expected value. The most chosen options are A & C in the poll 1 and B & D in poll 2 which maximise expected value.

Maximising expected value is rational, but you can also be rational with other choices.

Maximising expected value is rational, but you can also be rational with other choices.

Since the St Petersburg Paradox (Bernoulli, 1738), we know that valuing a gamble at its expected value can’t be the only acceptable solution.

Faced with a gamble with an infinite expected value (it’s possible!) people refuse to pay much to play it.

en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/St._Peter…

Faced with a gamble with an infinite expected value (it’s possible!) people refuse to pay much to play it.

en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/St._Peter…

Following Bernoulli, economists only assume that people maximise expected ‘utility’. An idea formalised by von Neumann and Morgenstern (1947).

This theory makes it totally fine to be risk averse and choose B (don’t play) in poll 1, for instance.

This theory makes it totally fine to be risk averse and choose B (don’t play) in poll 1, for instance.

But, the theory imposes constraints on choices for them to be consistent. One of the most surprising constraints:

In the poll 1, if you don’t take the single gamble A then, you *cannot* pick the 100 gambles C.

It seems very counter-intuitive since C offers excellent odds.

In the poll 1, if you don’t take the single gamble A then, you *cannot* pick the 100 gambles C.

It seems very counter-intuitive since C offers excellent odds.

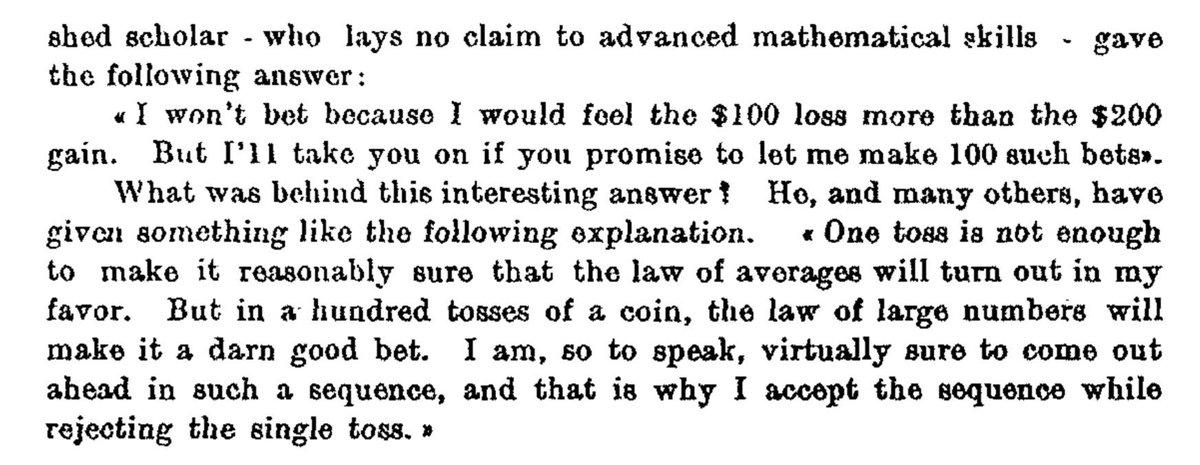

This point was made by Samuelson in a 1963 paper which contained poll 1’s question as an example.

casact.org/pubs/forum/94s…

casact.org/pubs/forum/94s…

The reason is that avoiding the single gamble A and picking the 100 gambles C would violate the independence axiom, one of the key principles behind expected utility.

Here is an explanation of why for the economists around:

link.springer.com/content/pdf/10…

Here is an explanation of why for the economists around:

link.springer.com/content/pdf/10…

So, if you choose to gamble only once but not 100 times, A&D (5%), or not once but a 100 times, B&C (29%), you violated the independence axiom, you were not a ‘homo economicus’.

Only those who always gambled or never gambled respected the independence axiom.

Only those who always gambled or never gambled respected the independence axiom.

The second poll, is the most famous violation of the independence axiom, it is one of the questions from the ‘Allais paradoxes’.

In 1952, Allais asked leading economists to answer a few questions at a conference in Paris. Many of them violated the independence axiom themselves!

In 1952, Allais asked leading economists to answer a few questions at a conference in Paris. Many of them violated the independence axiom themselves!

The violation of the independence axiom is easier to see in poll 2.

A & B both contain 89% chances of getting $500,000.

C & D both contain 89% chances of getting $0.

The independence axiom says that the choice between A&B and C&D should not depend on this common element.

A & B both contain 89% chances of getting $500,000.

C & D both contain 89% chances of getting $0.

The independence axiom says that the choice between A&B and C&D should not depend on this common element.

So only A&C and B&D respect the axiom of independence.

If you picked A&D (27%) or B&C (9%) you were not a homo economicus.

If you picked A&D (27%) or B&C (9%) you were not a homo economicus.

But were you ‘wrong’?

The most interesting aspect of the Allais paradox, is that the great Savage himself made the ‘wrong’ decision as he discusses in his second edition of The Foundations of Statistics. He then states that he made an ‘error’ and should change his mind.

The most interesting aspect of the Allais paradox, is that the great Savage himself made the ‘wrong’ decision as he discusses in his second edition of The Foundations of Statistics. He then states that he made an ‘error’ and should change his mind.

Furthermore experiments show that people often do not decide to change their mind when they are told that they violate the independence axiom.

So if the best economists violate the independence axiom and if people don’t care about it, in what way should we consider it ‘right’?

So if the best economists violate the independence axiom and if people don’t care about it, in what way should we consider it ‘right’?

Violations of the independence axiom have led to the development of non-Expected Utility theory, such as as Prospect Theory (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979).

Quiggin (1982) gave a rigorous theoretical underpinning to such models.

Quiggin (1982) gave a rigorous theoretical underpinning to such models.

These models drop the independence axiom and explain our choices better. For many modern economists it does not mean we are wrong/irrational.

So if you were not a homo economicus in the test, don’t worry: that’s just a matter of preferences!

(End)

So if you were not a homo economicus in the test, don’t worry: that’s just a matter of preferences!

(End)

Ping @JohnQuiggin @SylvainCF @causalinf @d_f_stone @Treich13 @Scientific_Bird @pro_fencesitter @_julesh_ @JohnHBillings @jonmvdavis @mukesh_tiwari @ChrisABogle @OguzGurerk @kccqzy @ab_ud @Uyakocin @axnicho @Catos_cat @saglam_sevket @bbraden98 @DanielWalshUcd @Sulphurcocky1

@JohnQuiggin @SylvainCF @causalinf @d_f_stone @Treich13 @Scientific_Bird @pro_fencesitter @_julesh_ @JohnHBillings @jonmvdavis @mukesh_tiwari @ChrisABogle @OguzGurerk @kccqzy @ab_ud @Uyakocin @axnicho @Catos_cat @saglam_sevket @bbraden98 @DanielWalshUcd @Sulphurcocky1 And @jahskillen @Mayi_Cervantes @HansHaneberg @f_bethke @Thavash @3rbhal

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh