Here's a really important #RailwaysExplained about how Britain's railways only really exist as a legacy of slavery…

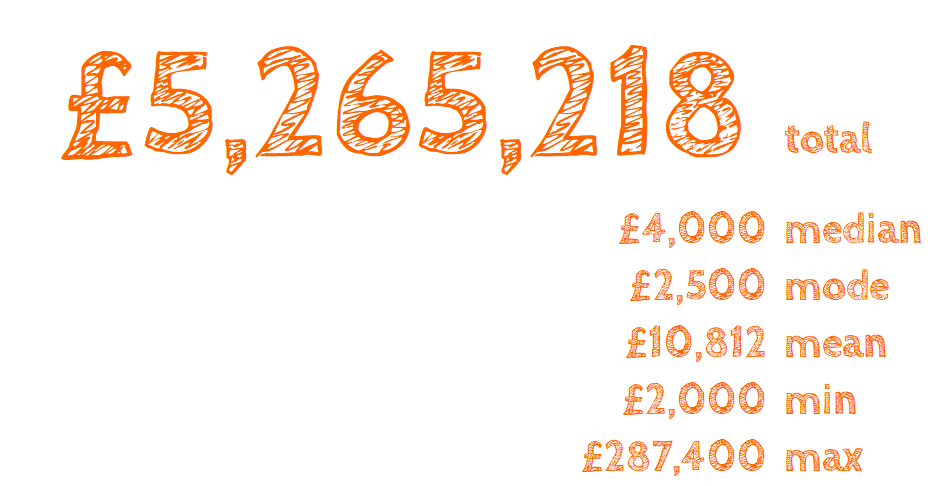

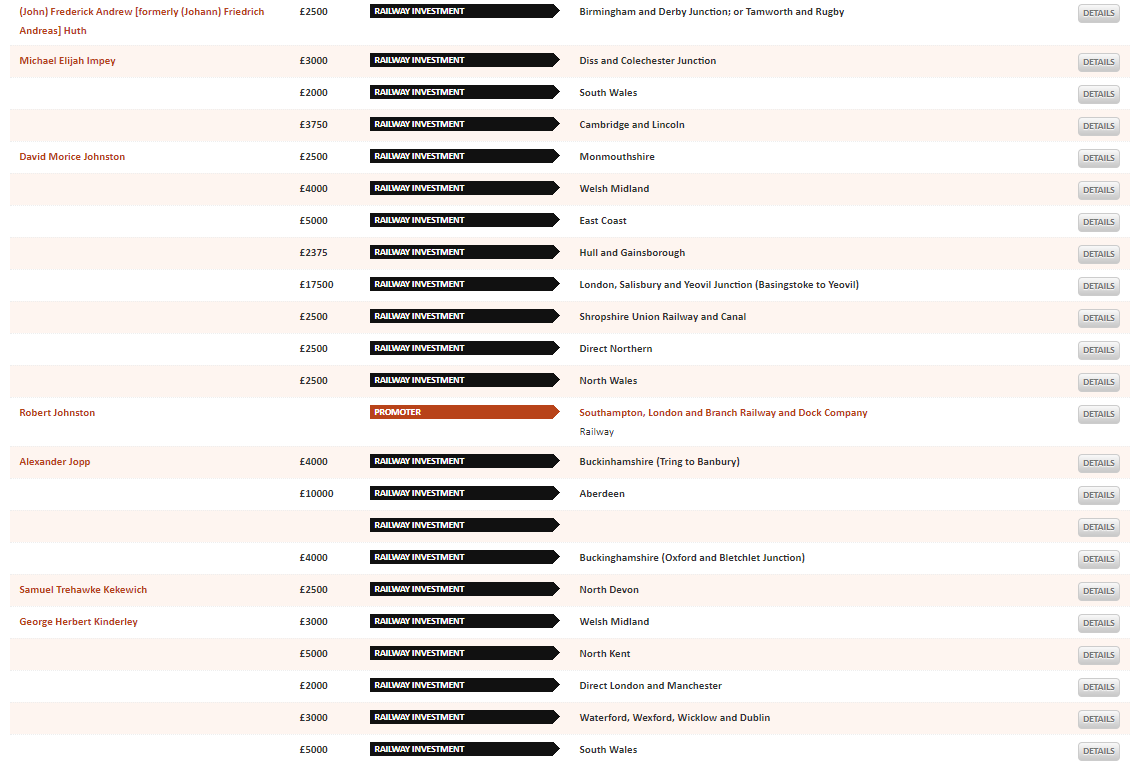

That's more than £19bn in today's money, and represented 40% of the government's budget at the time.

It is a legacy we cannot ignore.

You can read more about the research behind this #RailwaysExplained in @iansteadman's 2013 piece on @WiredUK: wired.co.uk/article/slaver…

However, more detail is clearly required.

CLAIM 1:

"Some compensation money may have gone into rail but there is absolutely no evidence it was substantial."

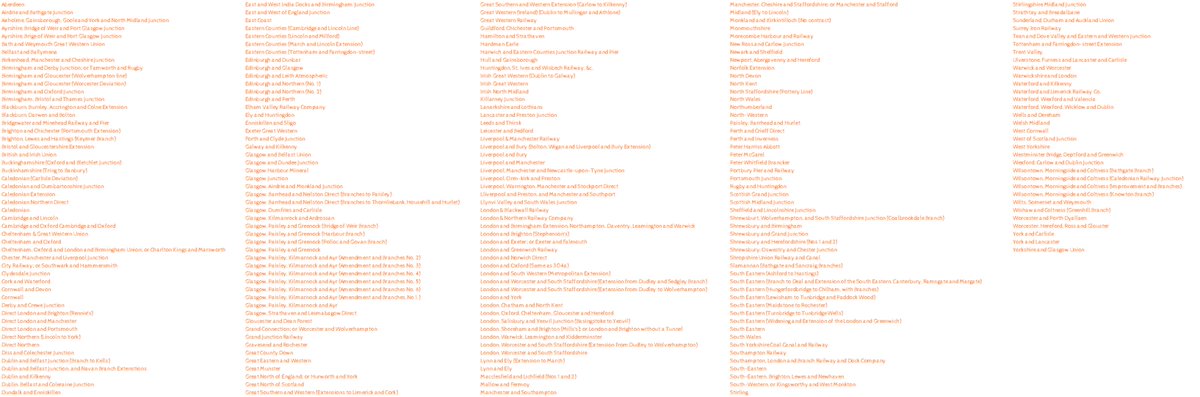

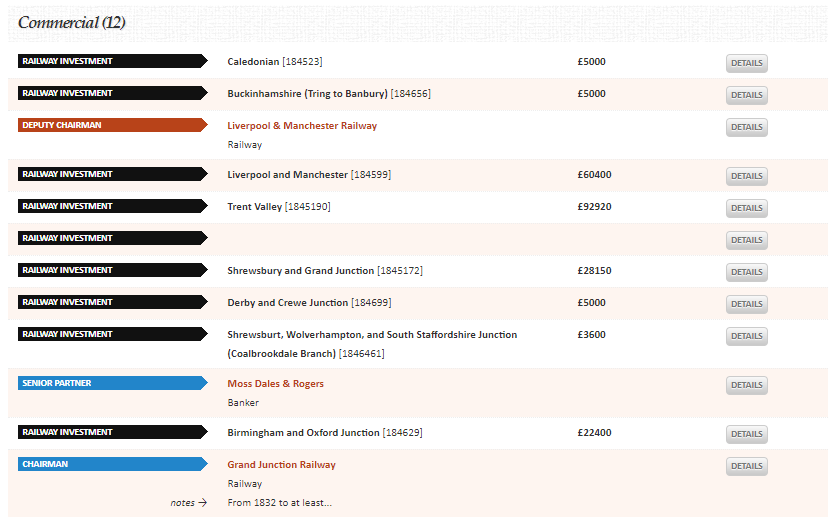

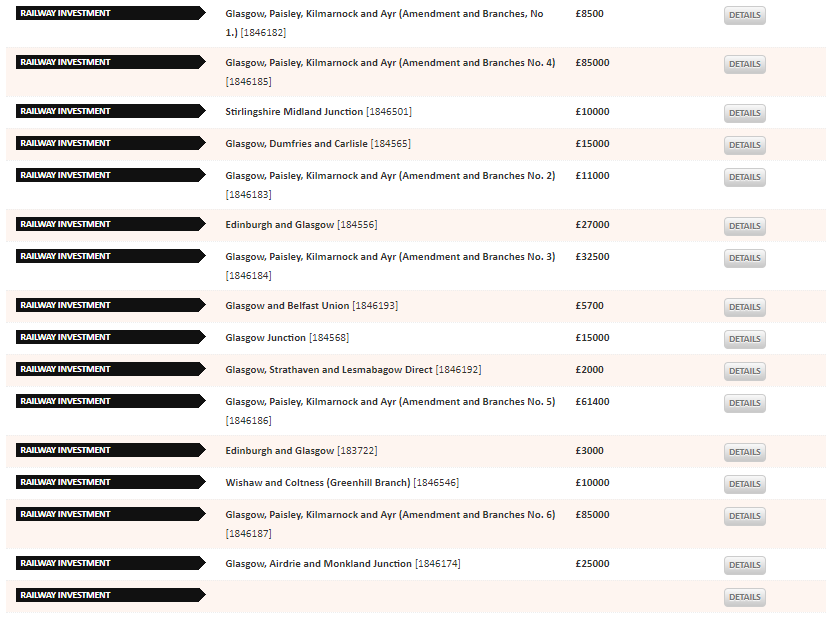

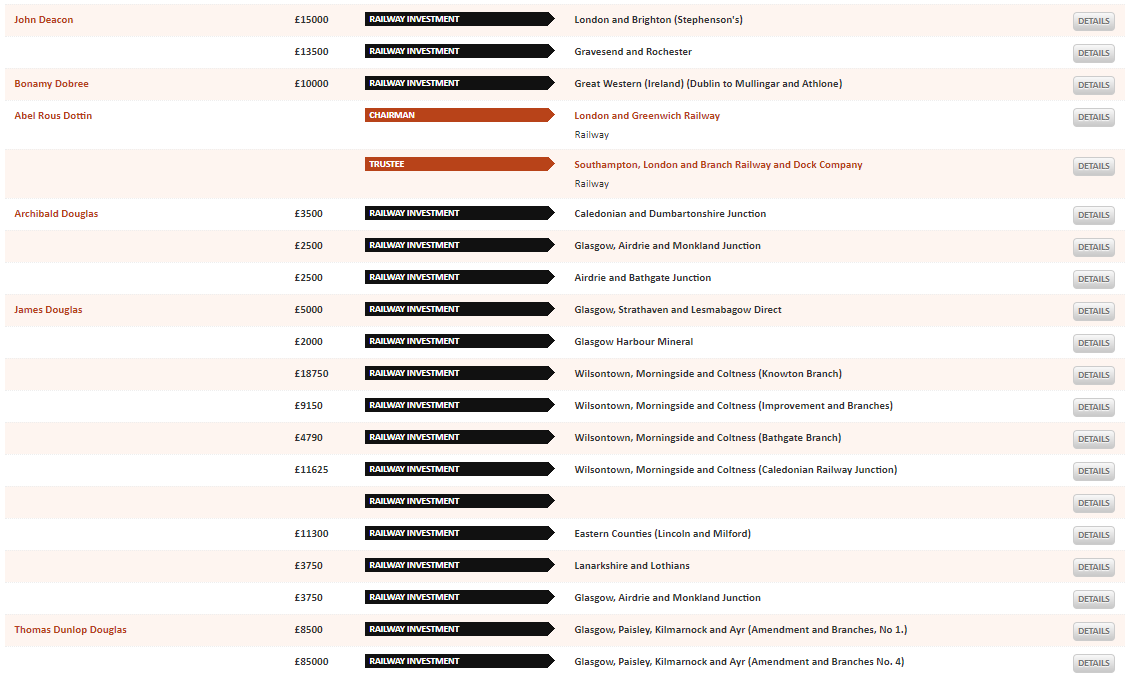

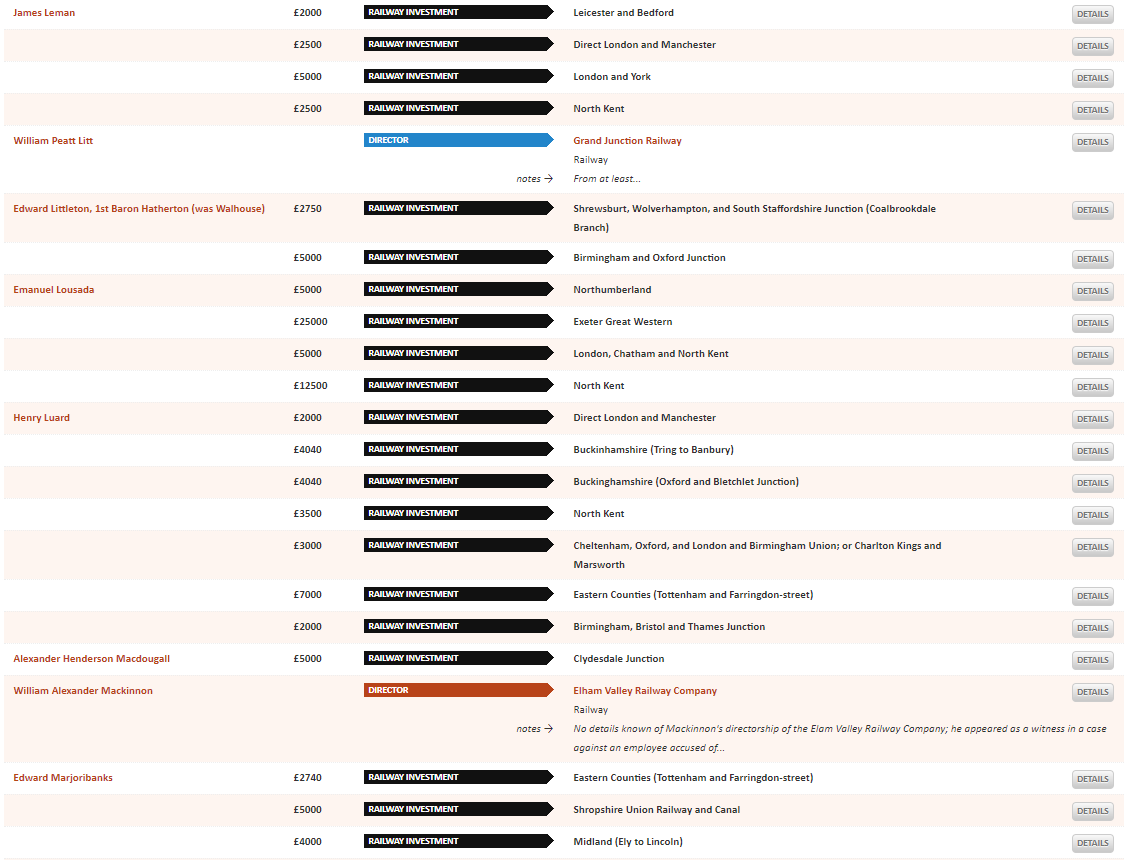

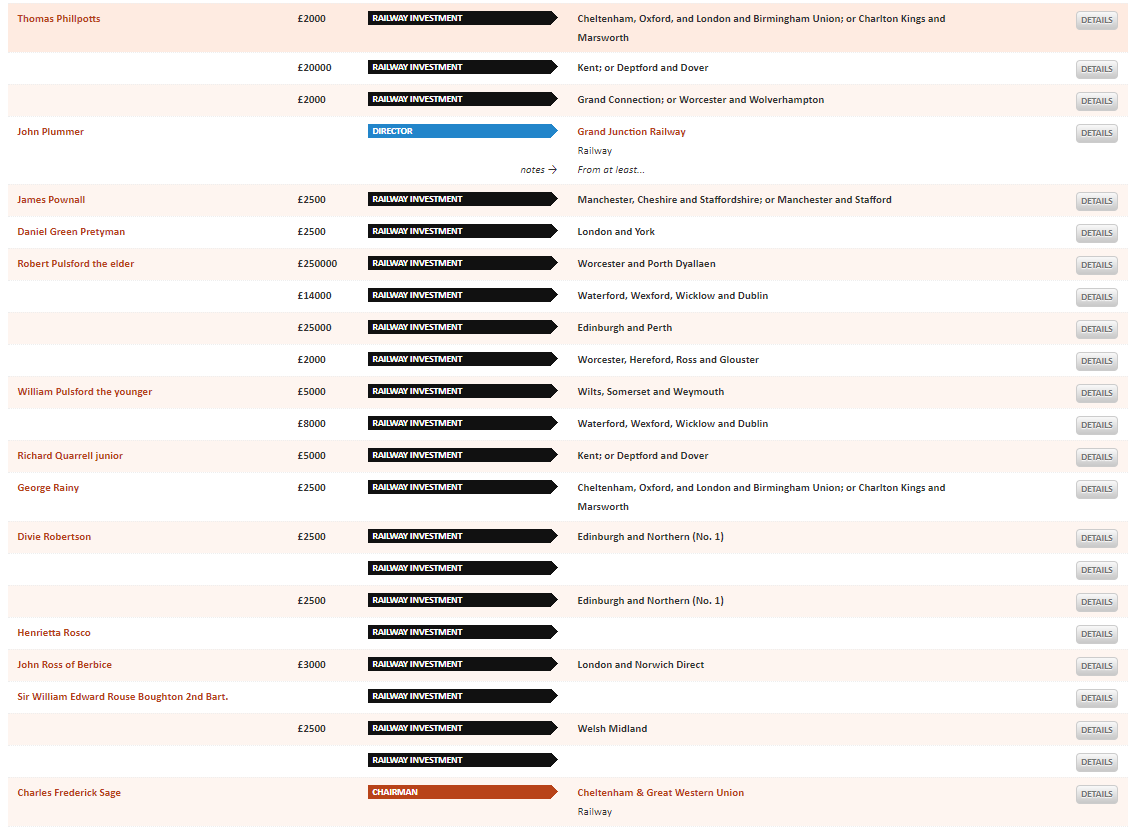

You can view the database here: ucl.ac.uk/lbs/commercial/

"Much of the early money came from northern industrialists who were nothing to do with the slave trade."

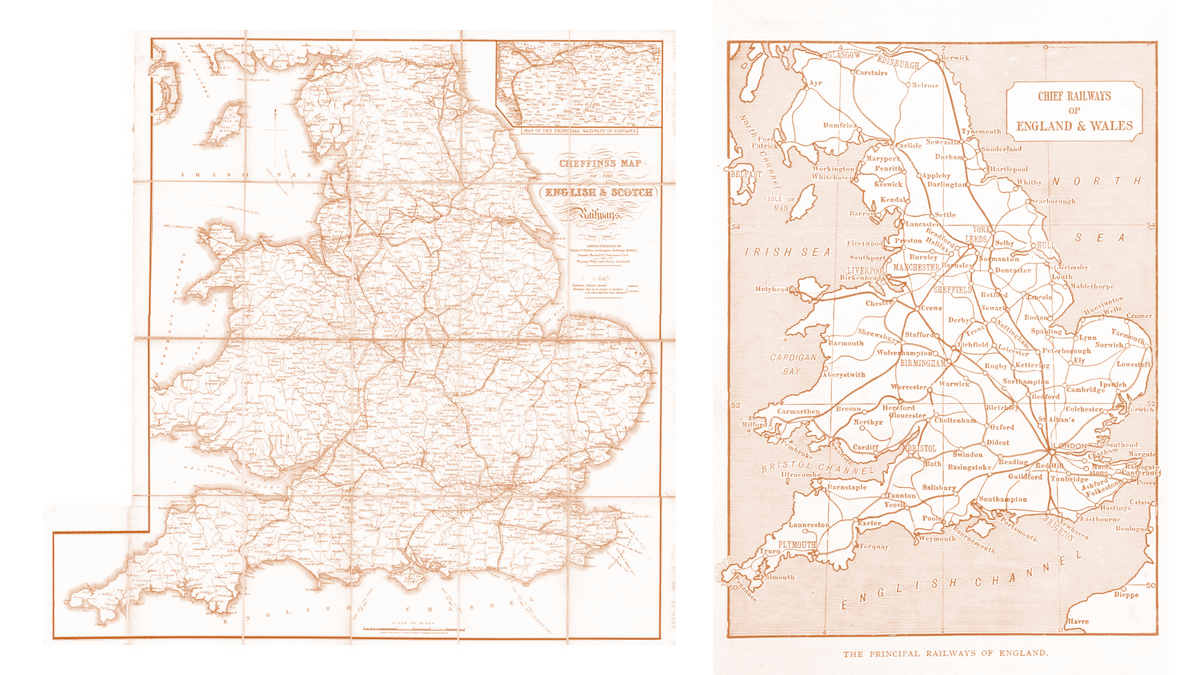

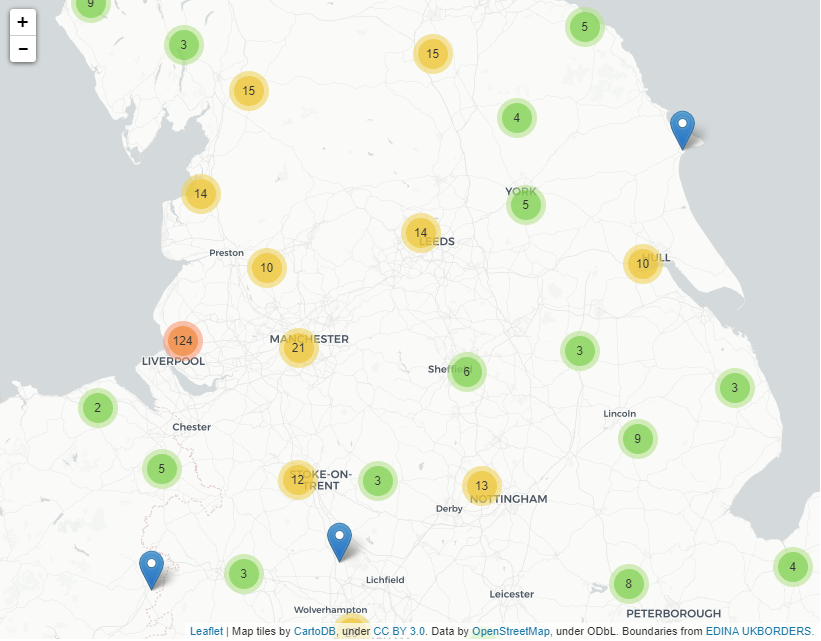

View this map: ucl.ac.uk/lbs/maps/brita…

"Much early rail investment came from the growing number of middle class people with small sums available and no connection to slavery."

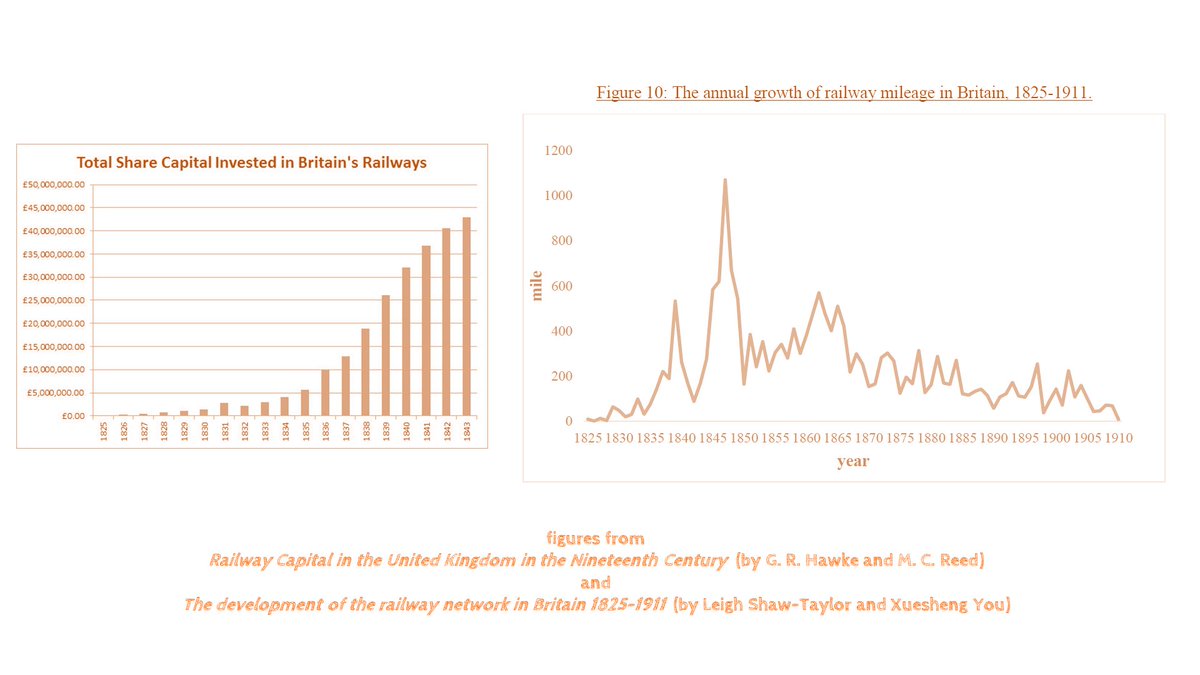

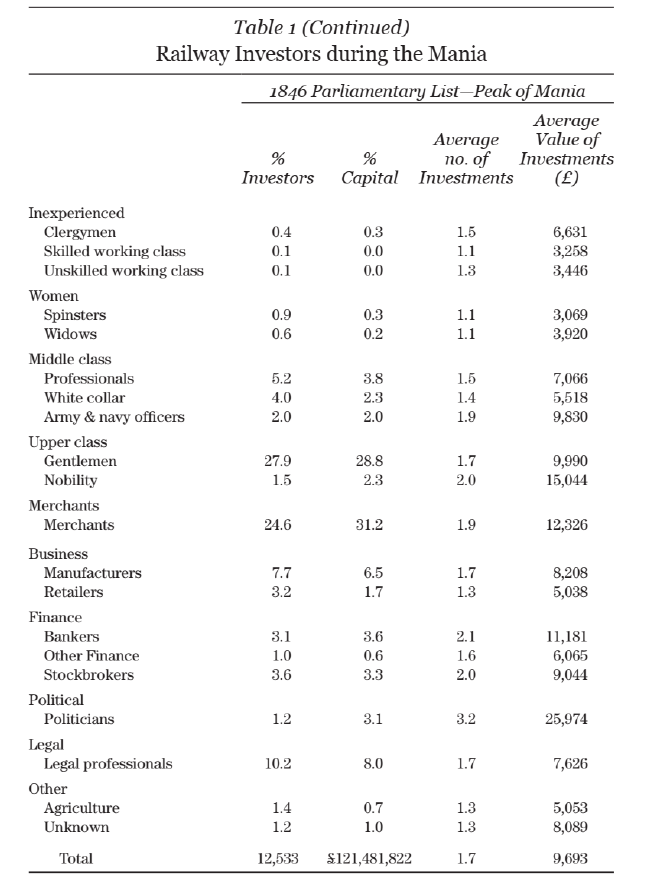

60% of railway capital came from large investors - middle class professionals only accounted for 3.8%.

If we look to the UCL database again, we can see that the middle classes represent a significant number of claims, even if the total value is not as large as for richer recipients.

"Just because the railway carried e.g. cotton (a trade that was one of the drivers behind its construction), you can't then go on to say that it was funded by slavery."

Is this aspect of history really so minor?

There is clearly more work to be done here, and hopefully this #RailwaysExplained has raised some awareness of the subject.

Rather than jumping for exceptions or defences, acknowledging and understanding slavery's legacy can allow us to move on. Hiding or diminishing it does not.