1/

Get a cup of coffee.

In this thread, I'm going to show you a simple way to think about "LTV vs CAC" trade-offs.

For those unfamiliar:

LTV = Life Time Value of a customer, and

CAC = Customer Acquisition Cost.

Get a cup of coffee.

In this thread, I'm going to show you a simple way to think about "LTV vs CAC" trade-offs.

For those unfamiliar:

LTV = Life Time Value of a customer, and

CAC = Customer Acquisition Cost.

2/

Imagine that you just returned from a vacation to India.

While there, you observed that many Indians don't buy their milk from grocery stores.

Instead, they get fresh milk delivered each morning to their doorstep.

Imagine that you just returned from a vacation to India.

While there, you observed that many Indians don't buy their milk from grocery stores.

Instead, they get fresh milk delivered each morning to their doorstep.

3/

There's a "milk man" in town who keeps a bunch of cows.

Every morning, this milk man wakes up at 4am, milks the cows, and bottles the milk.

By 6am, he is out delivering fresh milk to customers all over town.

There's a "milk man" in town who keeps a bunch of cows.

Every morning, this milk man wakes up at 4am, milks the cows, and bottles the milk.

By 6am, he is out delivering fresh milk to customers all over town.

4/

The milk man plays a vital role in society. To give you an idea:

"Super Star" Rajnikanth is one of India's most famous actors. "Annamalai" is one of his most famous movies.

Rajnikanth plays a milk man in this movie:

The milk man plays a vital role in society. To give you an idea:

"Super Star" Rajnikanth is one of India's most famous actors. "Annamalai" is one of his most famous movies.

Rajnikanth plays a milk man in this movie:

5/

Having just come back from India, you believe this fresh milk concept will work in the US too. This is your big business idea.

After all, who would say no to organic milk, completely free of preservatives, delivered to them so fresh it was *in the cow* just 2 hours ago?

Having just come back from India, you believe this fresh milk concept will work in the US too. This is your big business idea.

After all, who would say no to organic milk, completely free of preservatives, delivered to them so fresh it was *in the cow* just 2 hours ago?

6/

So you buy a ranch just outside the city.

You get some cows, milking equipment, bottling machines, etc.

You buy a refrigerated truck to transport and deliver the milk.

So you buy a ranch just outside the city.

You get some cows, milking equipment, bottling machines, etc.

You buy a refrigerated truck to transport and deliver the milk.

7/

You're in business.

Your company is called MAAS (Milk As A Service).

You have a "subscription plan": customers pay $100/month for a bottle of milk delivered each morning to their doorstep.

Customers can cancel anytime.

You're in business.

Your company is called MAAS (Milk As A Service).

You have a "subscription plan": customers pay $100/month for a bottle of milk delivered each morning to their doorstep.

Customers can cancel anytime.

8/

Of course, on Day 1, you have no customers.

Nobody knows about you or your revolutionary business.

You need an ad campaign to get the word out.

The more money you spend on ads, the more customers you'll sign up.

Of course, on Day 1, you have no customers.

Nobody knows about you or your revolutionary business.

You need an ad campaign to get the word out.

The more money you spend on ads, the more customers you'll sign up.

9/

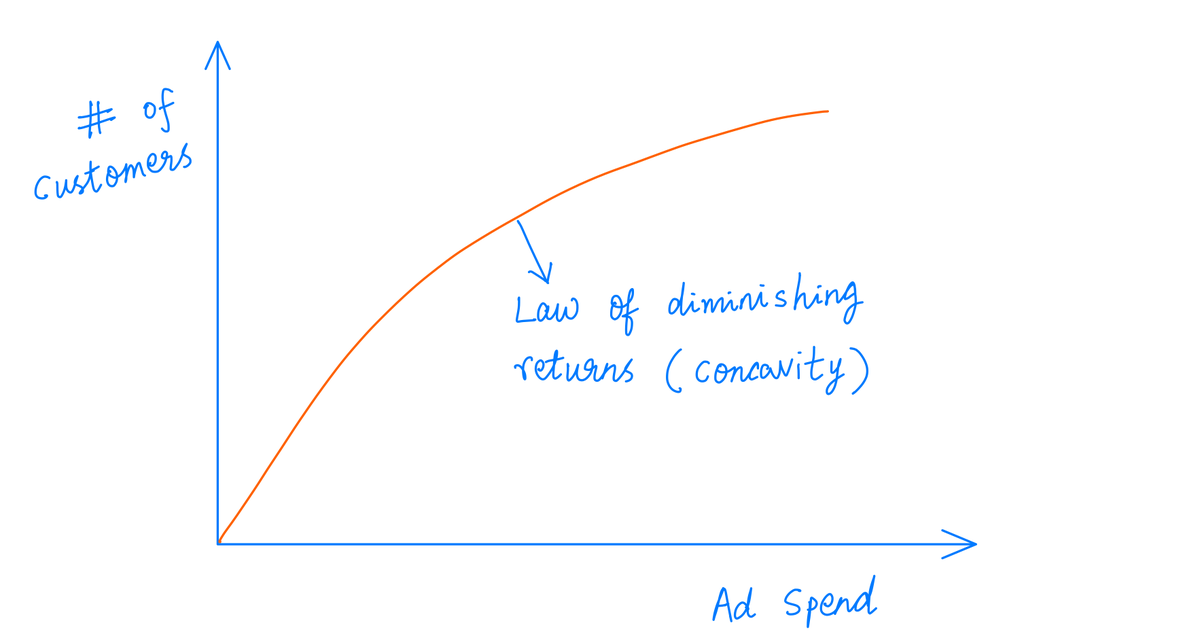

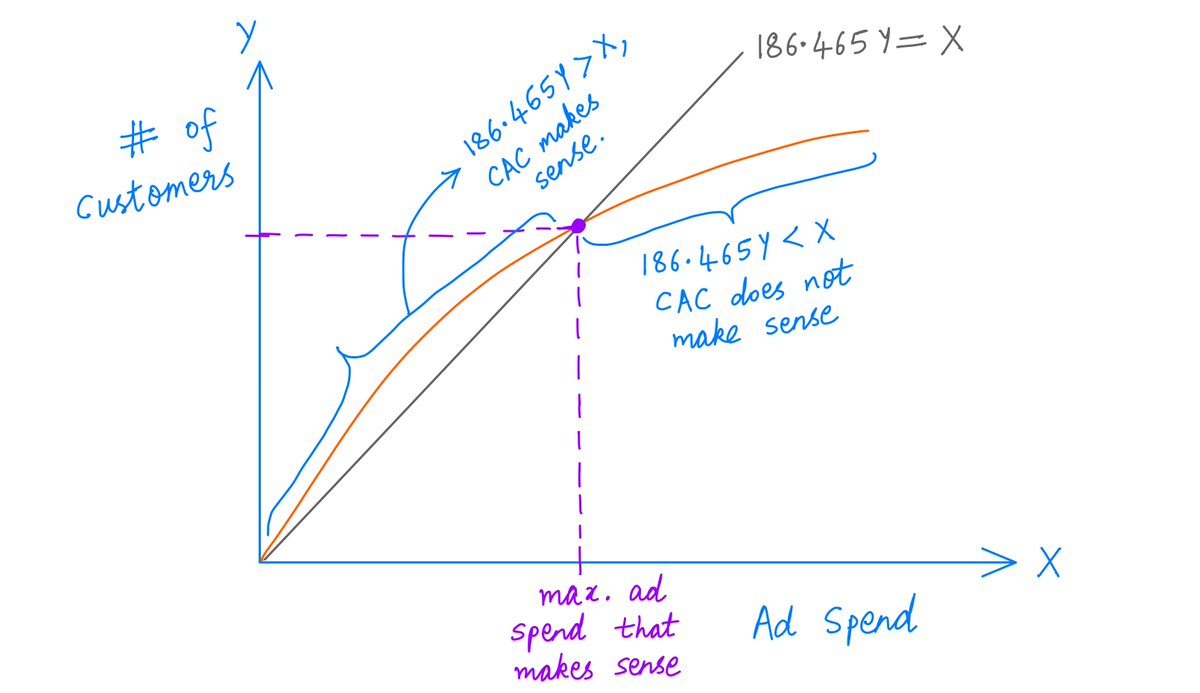

But the relationship between how much money you spend on ads and how many customers sign up is not linear.

Your first dollar of ad spend naturally buys you more than your 1000'th dollar.

There's a law of diminishing returns (or concavity, in fancy economics speak) at work:

But the relationship between how much money you spend on ads and how many customers sign up is not linear.

Your first dollar of ad spend naturally buys you more than your 1000'th dollar.

There's a law of diminishing returns (or concavity, in fancy economics speak) at work:

10/

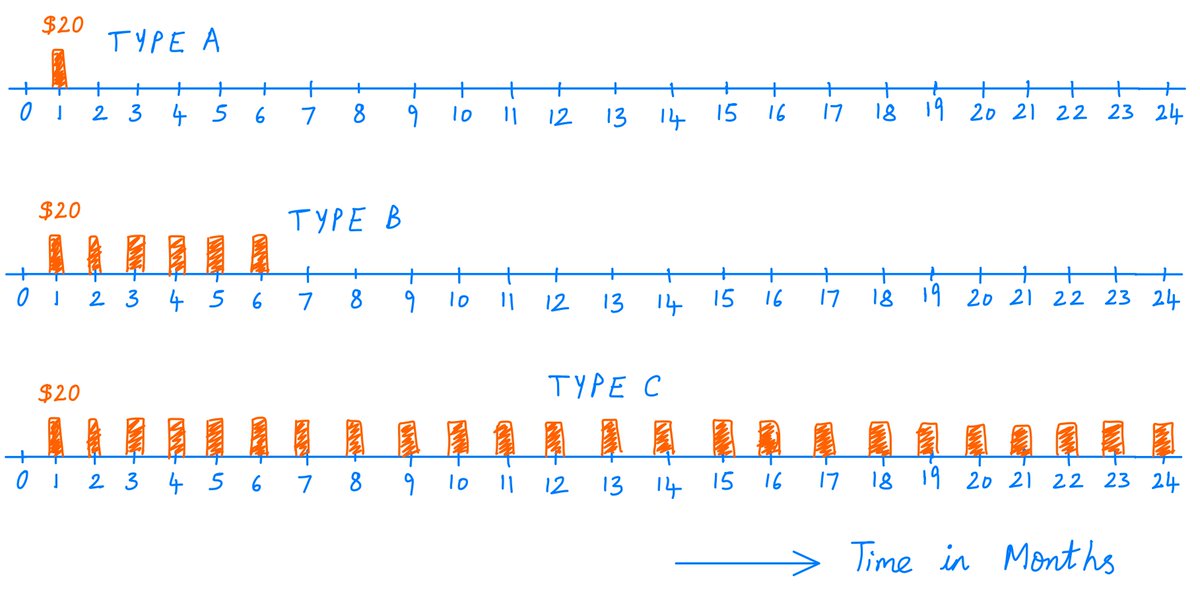

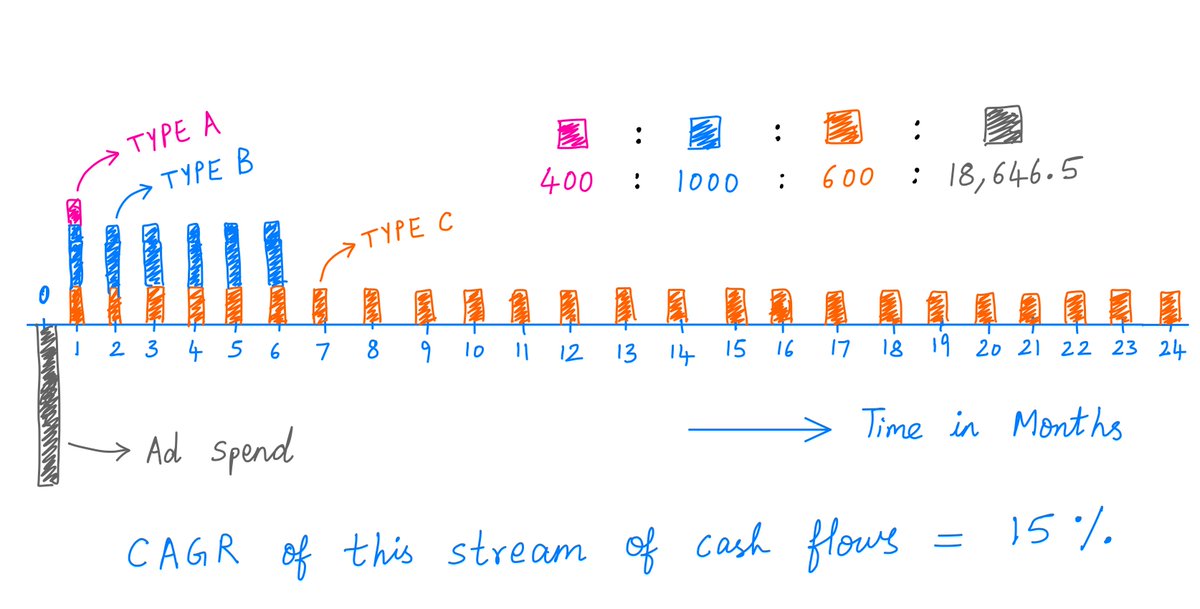

Also, not all customers who sign up are equal.

20% of your customers (let's call them Type A) just sign up for the novelty of it. They cancel after 1 month.

Another 50% (Type B customers) stay with you for 6 months.

The remaining 30% (Type C) stay with you for 2 years.

Also, not all customers who sign up are equal.

20% of your customers (let's call them Type A) just sign up for the novelty of it. They cancel after 1 month.

Another 50% (Type B customers) stay with you for 6 months.

The remaining 30% (Type C) stay with you for 2 years.

11/

Clearly, Type A customers are the least valuable, and Type C are the most valuable to your business, with Type B falling somewhere in between.

But how do you quantify the value of a customer to your business?

This is the "Life Time Value" (LTV) question.

Clearly, Type A customers are the least valuable, and Type C are the most valuable to your business, with Type B falling somewhere in between.

But how do you quantify the value of a customer to your business?

This is the "Life Time Value" (LTV) question.

12/

Say your operating margins in this business are about 20%.

That means, out of the $100 per month paid by each MAAS customer, you make $20 of pre-tax income.

So, as far as your business is concerned, each customer is just a stream of cash flows:

Say your operating margins in this business are about 20%.

That means, out of the $100 per month paid by each MAAS customer, you make $20 of pre-tax income.

So, as far as your business is concerned, each customer is just a stream of cash flows:

13/

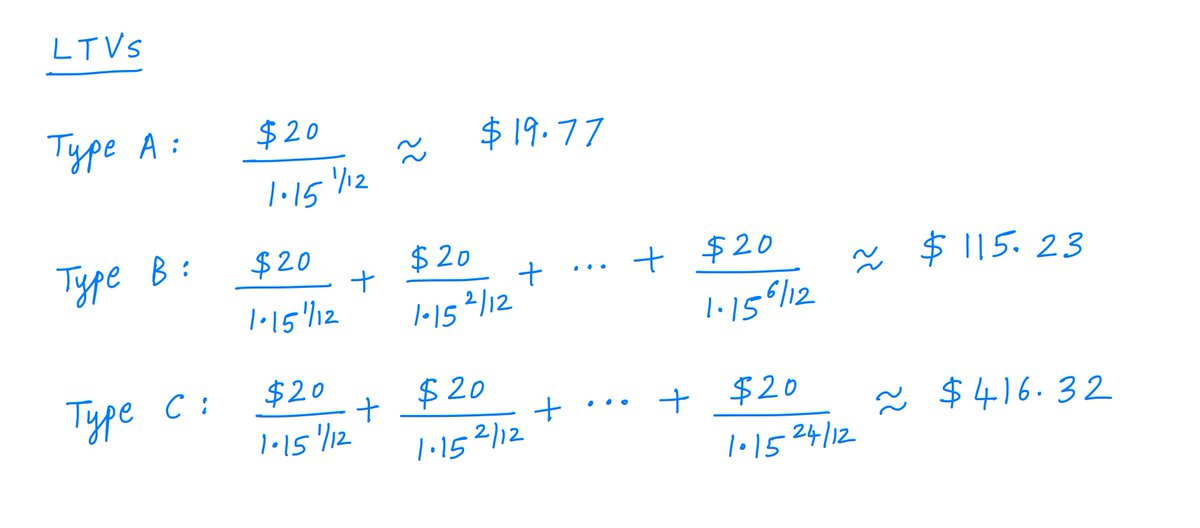

Key lesson 1: The Life Time Value (LTV) of a customer is the present value of cash flows from that customer.

Say you have a 15% hurdle rate. This is the minimum return you need to invest capital in this business.

Then you use a 15% discount rate to calculate customer LTVs:

Key lesson 1: The Life Time Value (LTV) of a customer is the present value of cash flows from that customer.

Say you have a 15% hurdle rate. This is the minimum return you need to invest capital in this business.

Then you use a 15% discount rate to calculate customer LTVs:

14/

Of course, these customers didn't come for free. You had to incur advertising expenses to sign them up, remember?

That's the other side of the coin: there's a cost to acquire customers. This is called Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC).

In this example, CAC is your ad spend.

Of course, these customers didn't come for free. You had to incur advertising expenses to sign them up, remember?

That's the other side of the coin: there's a cost to acquire customers. This is called Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC).

In this example, CAC is your ad spend.

15/

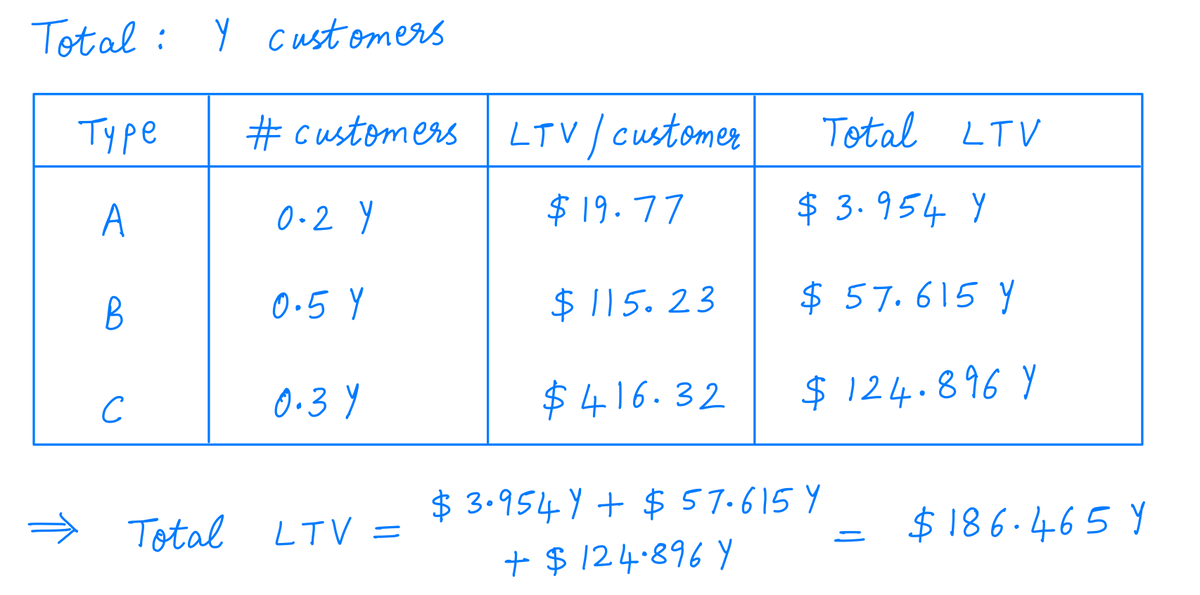

Let's say you spent $X on ads, and that bought you Y customers.

Given your "customer mix" (20% Type A, 50% Type B, and 30% Type C), how much LTV did your ad spend end up buying you?

The answer is $186.465*Y, as this calculation shows:

Let's say you spent $X on ads, and that bought you Y customers.

Given your "customer mix" (20% Type A, 50% Type B, and 30% Type C), how much LTV did your ad spend end up buying you?

The answer is $186.465*Y, as this calculation shows:

16/

Key lesson 2: Paraphrasing Buffett, CAC is what you pay, LTV is what you get. The trade-off works in your favor only if LTV exceeds CAC.

In this example, your CAC is $X and your LTV is $186.465*Y. Ad spending only makes sense up to the purple point shown below:

Key lesson 2: Paraphrasing Buffett, CAC is what you pay, LTV is what you get. The trade-off works in your favor only if LTV exceeds CAC.

In this example, your CAC is $X and your LTV is $186.465*Y. Ad spending only makes sense up to the purple point shown below:

17/

If you choose the maximum ad spend that makes sense, your cash flows will look like this pic:

There will be a big CAC *outflow* in the beginning. It will be followed by LTV *inflows* in subsequent months.

The CAGR of these cash flows will be exactly 15%, your hurdle rate.

If you choose the maximum ad spend that makes sense, your cash flows will look like this pic:

There will be a big CAC *outflow* in the beginning. It will be followed by LTV *inflows* in subsequent months.

The CAGR of these cash flows will be exactly 15%, your hurdle rate.

18/

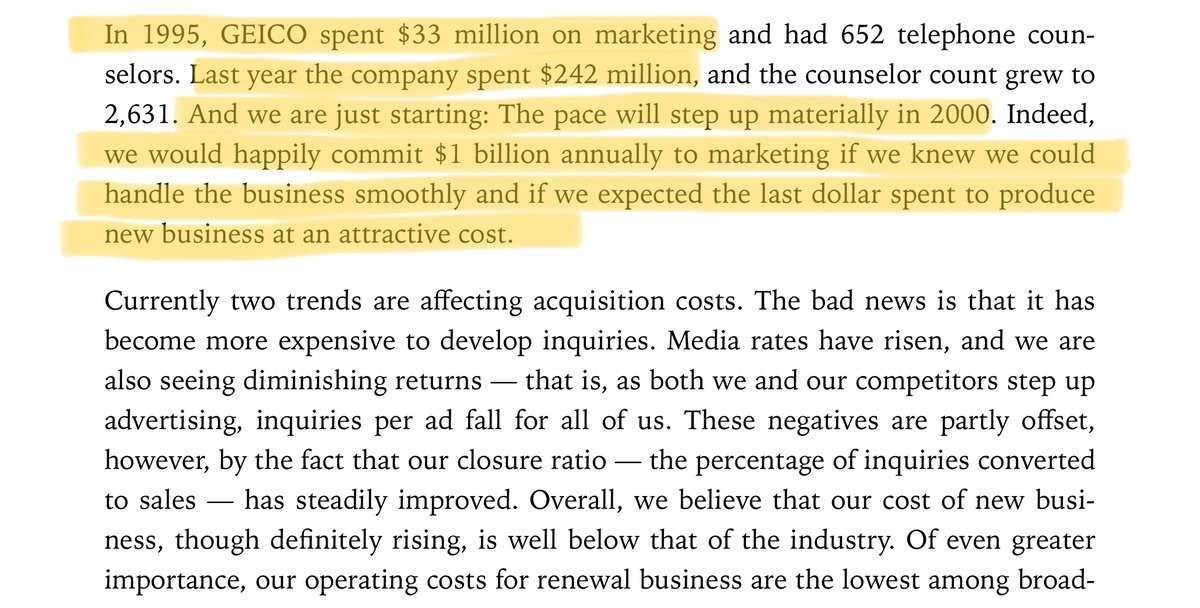

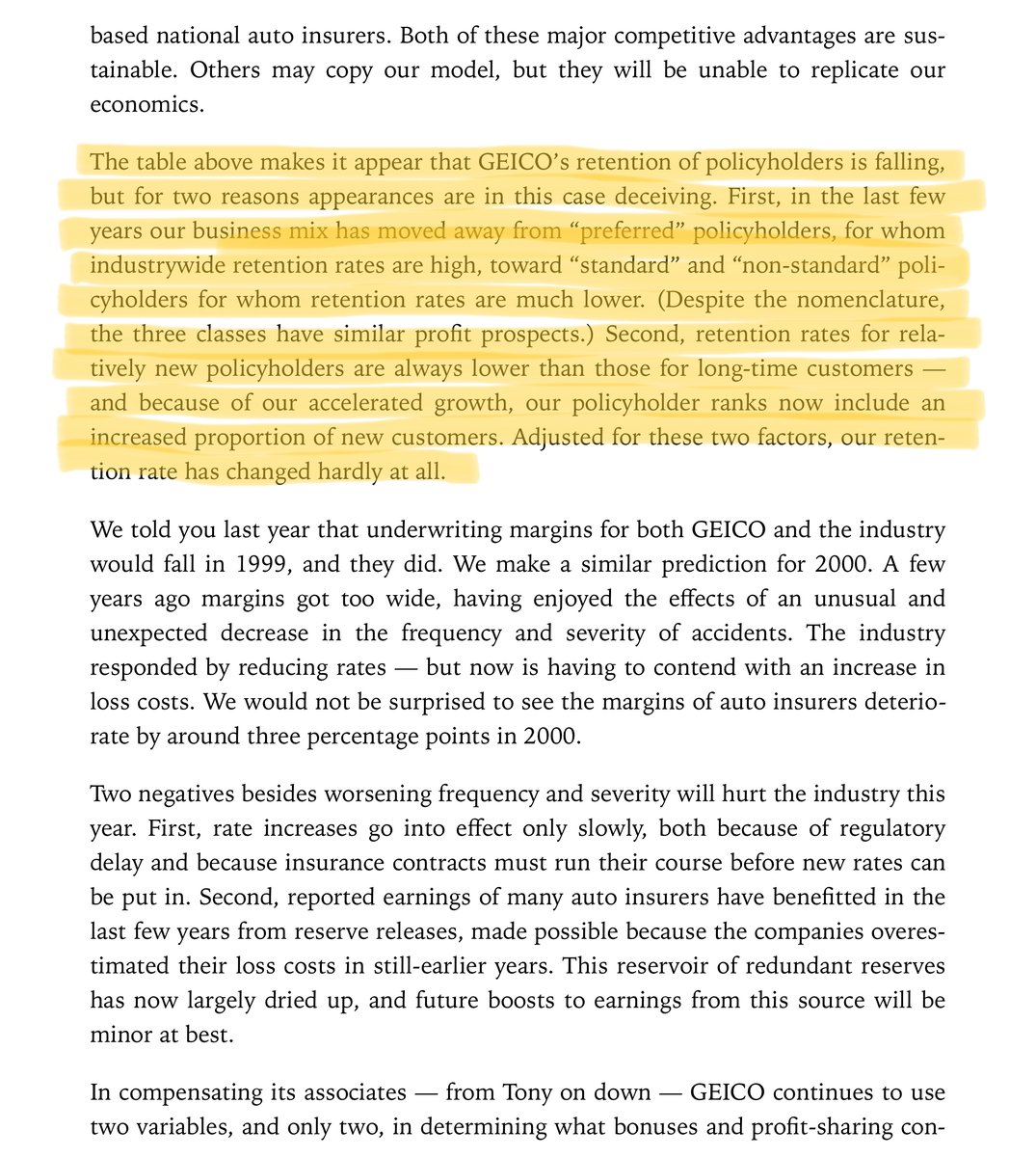

This LTV vs CAC trade-off is a good way to think about many real-life businesses.

For example, GEICO, T-Mobile, Comcast, Trupanion, Dollar Shave Club -- all incur CAC via money spent on advertising to get LTV via customers signing up for subscriptions.

This LTV vs CAC trade-off is a good way to think about many real-life businesses.

For example, GEICO, T-Mobile, Comcast, Trupanion, Dollar Shave Club -- all incur CAC via money spent on advertising to get LTV via customers signing up for subscriptions.

19/

Many software companies (Microsoft, Adobe, etc.) have also moved to a subscription model (SaaS).

CAC for these companies is the money spent on advertising *and* the money spent on adding new features to their products (R&D). The goal is again LTV via subscription revenue.

Many software companies (Microsoft, Adobe, etc.) have also moved to a subscription model (SaaS).

CAC for these companies is the money spent on advertising *and* the money spent on adding new features to their products (R&D). The goal is again LTV via subscription revenue.

20/

With real-life public companies, there are 4 Cs that shape the LTV vs CAC trade-off: 1) Concavity, 2) Churn, 3) Cash flows, and 4) CAGR.

With real-life public companies, there are 4 Cs that shape the LTV vs CAC trade-off: 1) Concavity, 2) Churn, 3) Cash flows, and 4) CAGR.

21/

Concavity means the diminishing returns a company gets from CAC spending.

If watching 100 GEICO ads did not convince you to "spend 15 minutes to save 15% on car insurance", what are the chances the 101'st ad will nudge you over the top?

Concavity means the diminishing returns a company gets from CAC spending.

If watching 100 GEICO ads did not convince you to "spend 15 minutes to save 15% on car insurance", what are the chances the 101'st ad will nudge you over the top?

22/

Churn means customers cancel their subscriptions. This reduces their LTV to companies.

For example, many people signed up for Blue Apron for the novelty of meal-kit delivery. But they churned out after a month or two -- so Blue Apron found it difficult to recoup its CAC.

Churn means customers cancel their subscriptions. This reduces their LTV to companies.

For example, many people signed up for Blue Apron for the novelty of meal-kit delivery. But they churned out after a month or two -- so Blue Apron found it difficult to recoup its CAC.

23/

Cash flows are the recurring operating income a company makes from subscribers.

Cash flows are driven mainly by the number of subscribers, subscription rates (e.g., $10/month vs $5/month), renewal cycles (e.g., monthly vs yearly), and the operating margins of the business.

Cash flows are the recurring operating income a company makes from subscribers.

Cash flows are driven mainly by the number of subscribers, subscription rates (e.g., $10/month vs $5/month), renewal cycles (e.g., monthly vs yearly), and the operating margins of the business.

24/

CAGR is the rate of return the company makes -- considering both CAC outflows and LTV inflows.

Generally, if a company is able to get high LTV/CAC CAGRs, it will also earn favorable returns on incremental invested capital (ROIIC). These are good businesses to own long term.

CAGR is the rate of return the company makes -- considering both CAC outflows and LTV inflows.

Generally, if a company is able to get high LTV/CAC CAGRs, it will also earn favorable returns on incremental invested capital (ROIIC). These are good businesses to own long term.

25/

One more thing: in GAAP accounting, advertising and R&D are usually expensed immediately rather than capitalized -- even if these are CAC expenses that generate LTV for years to come.

So, GAAP earnings of good subscription businesses can understate true economic earnings.

One more thing: in GAAP accounting, advertising and R&D are usually expensed immediately rather than capitalized -- even if these are CAC expenses that generate LTV for years to come.

So, GAAP earnings of good subscription businesses can understate true economic earnings.

26/

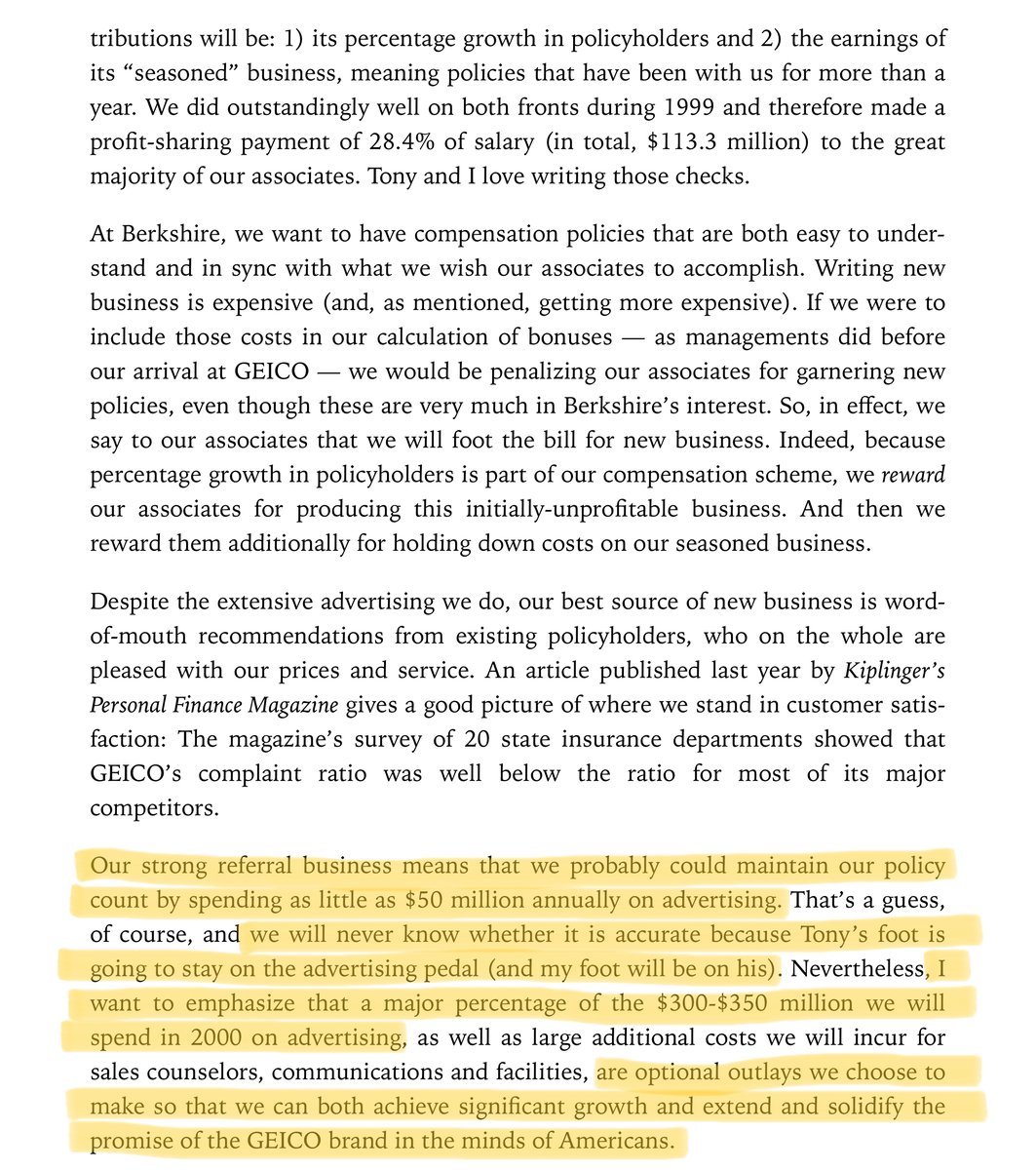

I'll leave you with some references containing more insights on LTV and CAC.

LTV and CAC may seem like newfangled terms, but Buffett was talking about this trade-off way back in 1999!

berkshirehathaway.com/letters/1999ht…

I'll leave you with some references containing more insights on LTV and CAC.

LTV and CAC may seem like newfangled terms, but Buffett was talking about this trade-off way back in 1999!

berkshirehathaway.com/letters/1999ht…

27/

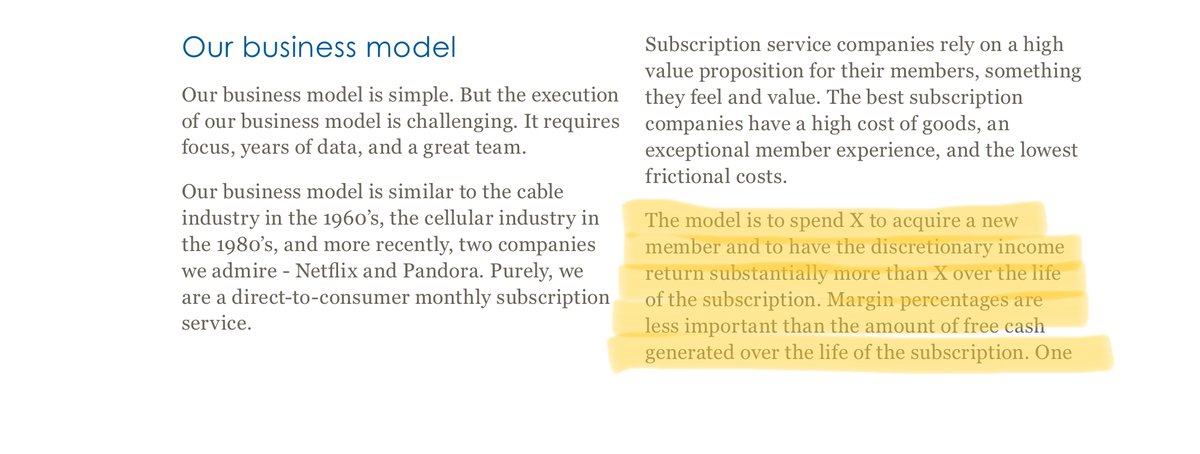

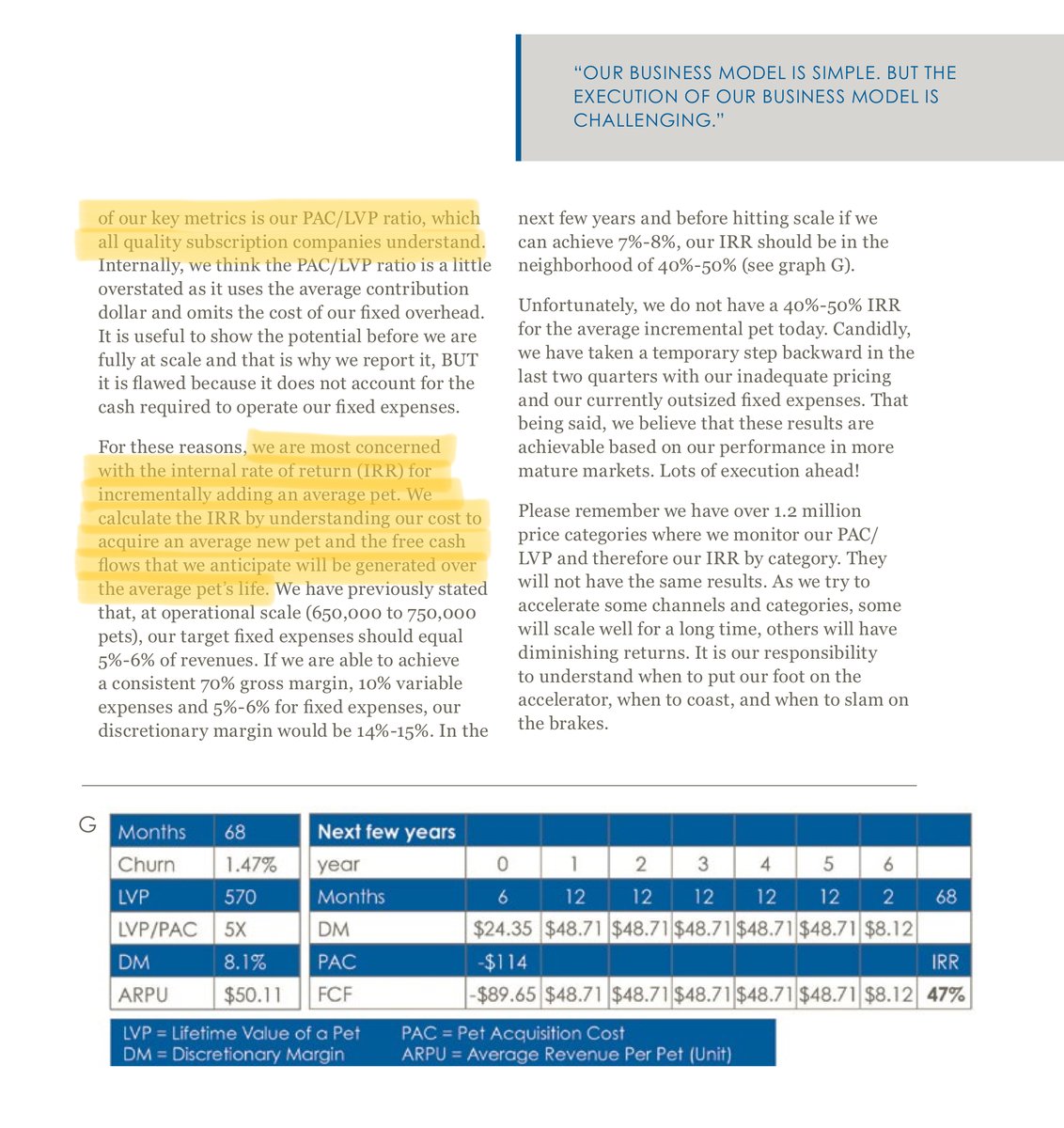

In 2014, Darryl Rawlings, the founder and CEO of Trupanion (a pet insurance company), wrote an excellent shareholder letter describing the LTV vs CAC trade-off for his company:

s21.q4cdn.com/119804282/file…

The thread you're reading now was partly inspired by this letter.

In 2014, Darryl Rawlings, the founder and CEO of Trupanion (a pet insurance company), wrote an excellent shareholder letter describing the LTV vs CAC trade-off for his company:

s21.q4cdn.com/119804282/file…

The thread you're reading now was partly inspired by this letter.

28/

Travis Fairchild @tbfairchild has an excellent write-up on the OSAM blog about how GAAP expensing of advertising and R&D CACs can lead to understated earnings and book values:

osam.com/Commentary/neg…

Cc: @jposhaughnessy

Travis Fairchild @tbfairchild has an excellent write-up on the OSAM blog about how GAAP expensing of advertising and R&D CACs can lead to understated earnings and book values:

osam.com/Commentary/neg…

Cc: @jposhaughnessy

29/

Finally, @Greenbackd did an excellent podcast episode with @BluegrassCap about the concept of unit economics and the LTV vs CAC trade-off:

Finally, @Greenbackd did an excellent podcast episode with @BluegrassCap about the concept of unit economics and the LTV vs CAC trade-off:

30/

If you've come this far, you have a tremendous amount of perseverance! Kudos!

Thanks for reading! Enjoy your weekend!

/End

If you've come this far, you have a tremendous amount of perseverance! Kudos!

Thanks for reading! Enjoy your weekend!

/End

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh