Get a cup of coffee.

In this thread, I'll help you work out how much money you need to retire.

The goal is simple.

You want to accumulate a *large* portfolio of assets.

How large?

Well, you should be able to quit your job. And you and your family should be able to live comfortably for decades -- just off of the income generated by this portfolio.

This is the crux of the "FIRE" movement.

FIRE stands for "Financially Independent, Retired Early".

The basic philosophy is: keep your spending needs low. Save a large portion of your income. Invest these savings. With luck, you'll be able to retire early.

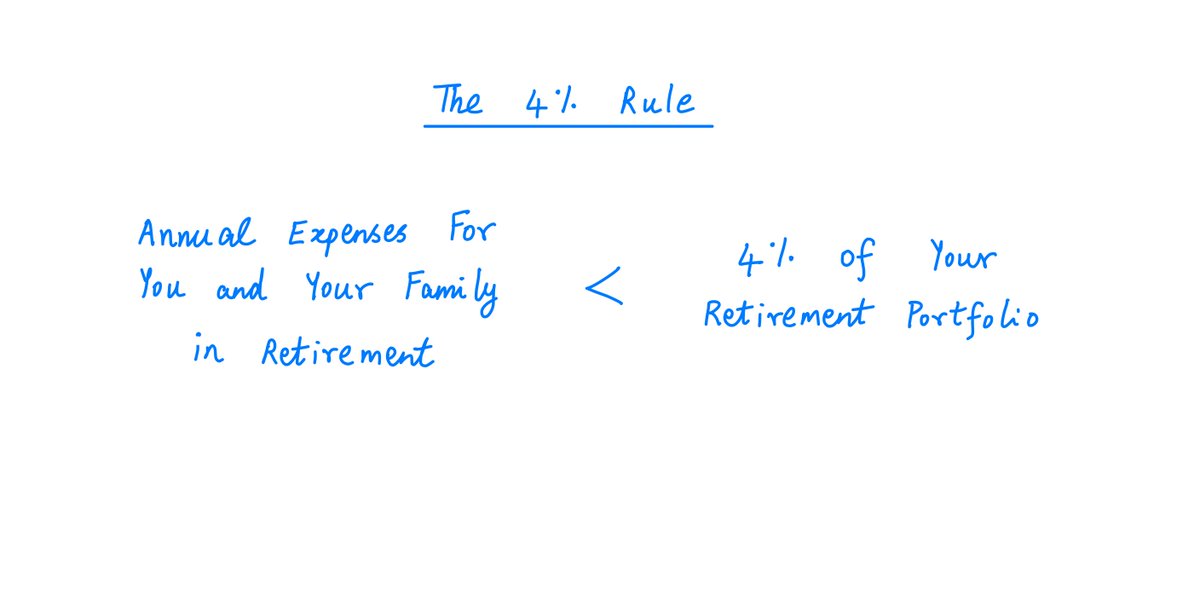

Here's the simple logic behind the 4% rule.

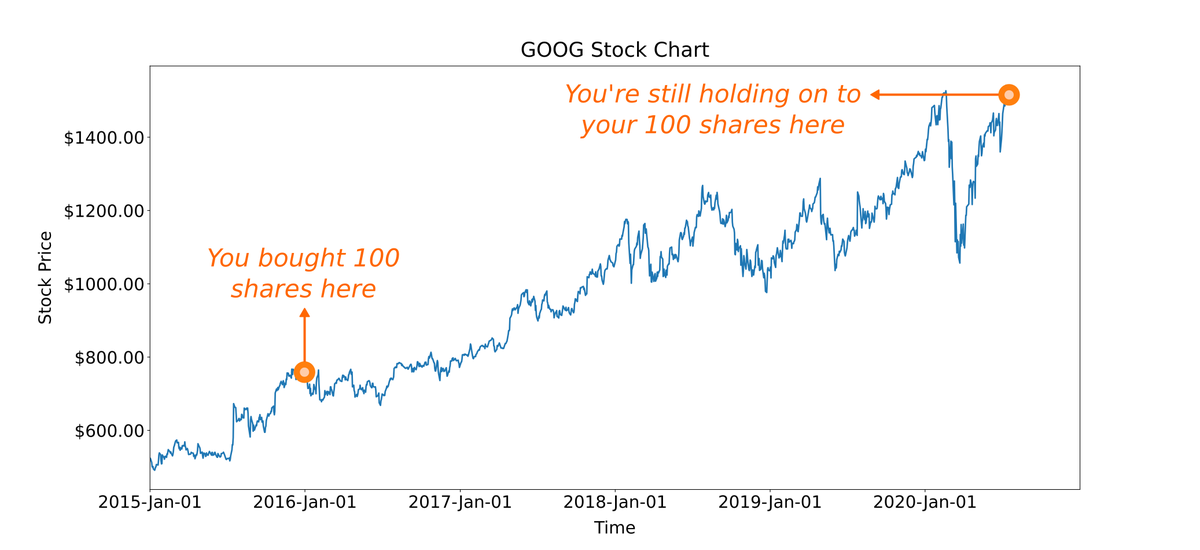

Suppose your retirement portfolio is a well-diversified basket of stocks, like the S&P 500.

Historically, such a basket of stocks has returned ~7% per year, plus ~2% in dividends. This is a total return of ~9%.

Assuming your annual expenses grow at ~2% per year (roughly the rate of inflation), your portfolio -- which is growing much faster at ~9% per year -- should have no trouble financing your expenses in perpetuity.

This means you'll never run out of money.

Let's flesh this out in some detail.

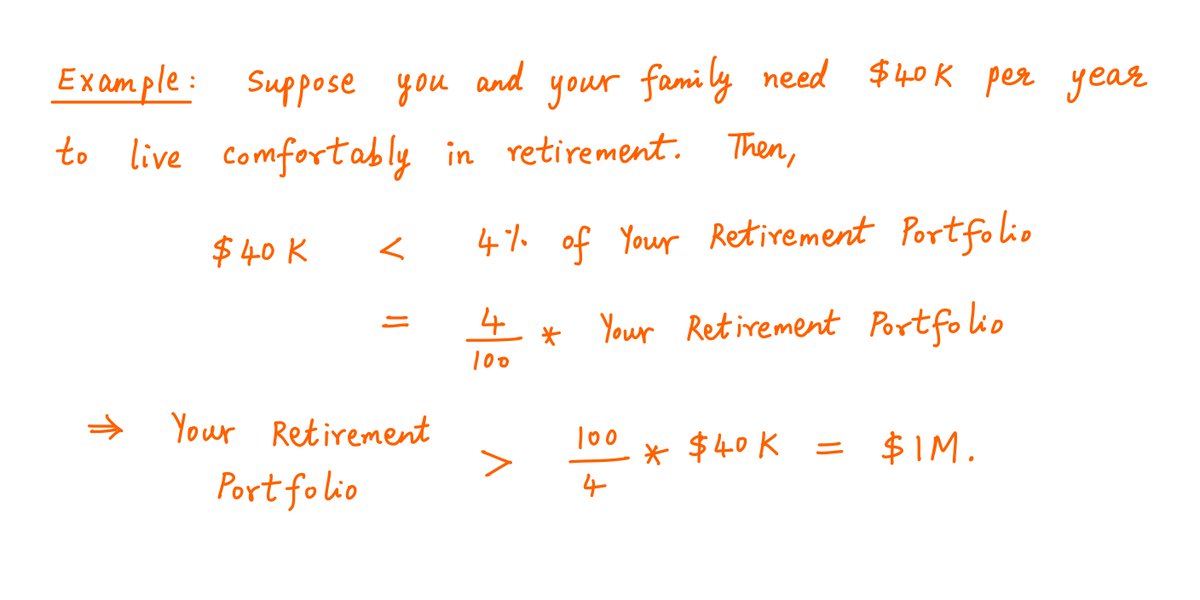

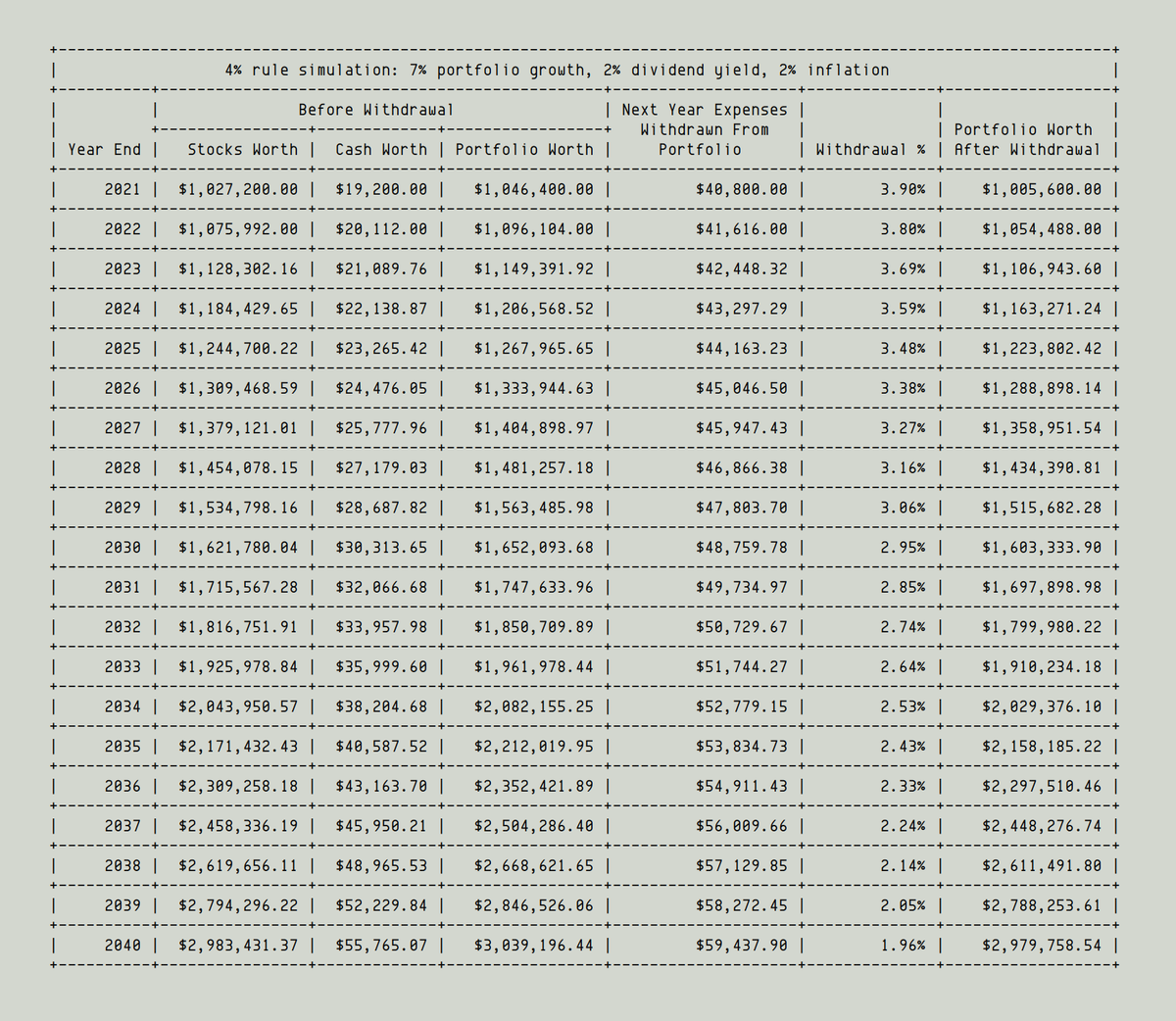

Say you retire on Dec 31 2020. Your annual expenses are $40K. Following the 4% rule, you've amassed a $1M portfolio.

On Dec 31 2020, say you withdraw from your portfolio the entire $40K you need for 2021. Your portfolio is now $960K.

Fast forward 1 year. It's Dec 31 2021.

Your $960K portfolio has grown by 7%. It's now worth $1,027,200.

In addition, you have $19,200 cash in your brokerage account: the 2% dividend your $960K has earned in 2021.

So your total portfolio worth is $1,046,400.

Assuming ~2% inflation, your expenses for 2022 will be $40,800, which again you withdraw from your portfolio.

But note this: the second withdrawal is *not* 4% of your portfolio any more. It's only ~3.9%.

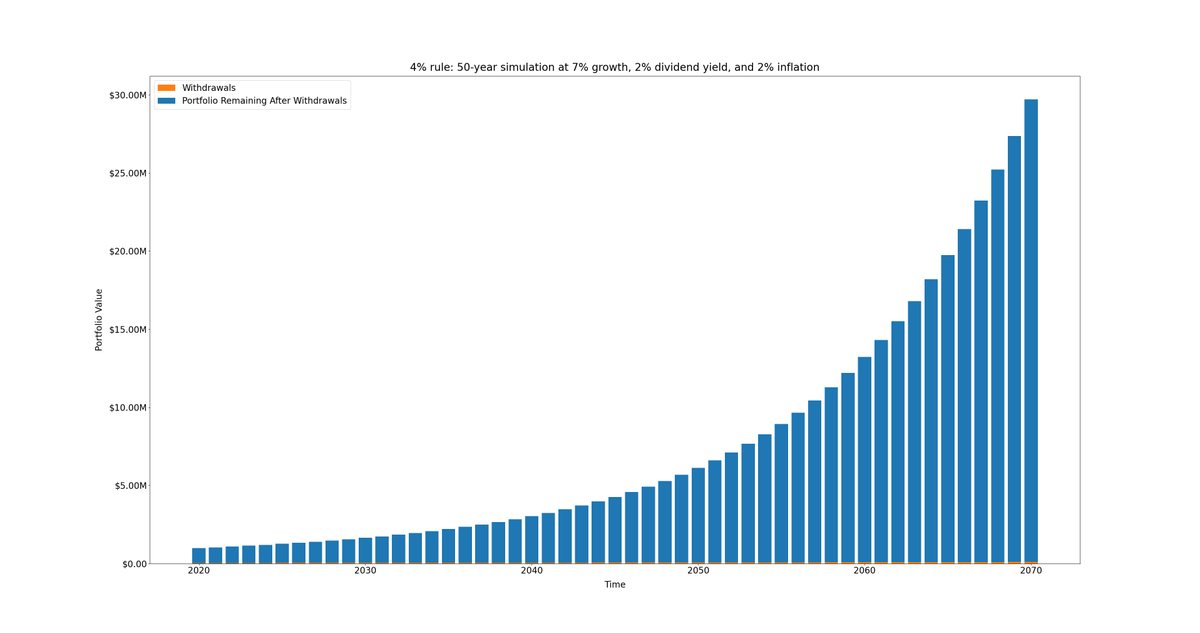

That's the best case scenario for the 4% rule: over time, your withdrawals become smaller and smaller fractions of your portfolio.

And it's exactly what happens if your stocks grow at a steady 7% while giving you a steady 2% dividend yield, and inflation is contained at 2%.

So it's settled then?

You just have to follow the 4% rule.

Just accumulate a portfolio that's 25 times your annual expenses. And you can retire on it. Right?

Not so fast.

Returns from stocks are anything but steady.

Dividend yields are anything but steady.

Inflation is anything but steady.

We can't make a major retirement decision based on assuming a steady (7%, 2%, 2%) for these parameters. That would be foolhardy.

Luckily for us, we have Prof. Robert Shiller (@RobertJShiller).

Prof. Shiller has painstakingly accumulated historical data on US stock market returns, dividends, and inflation -- going back all the way to 1871!

And he's made it freely available: econ.yale.edu/~shiller/data.…

With this data, we can "backtest" the 4% rule.

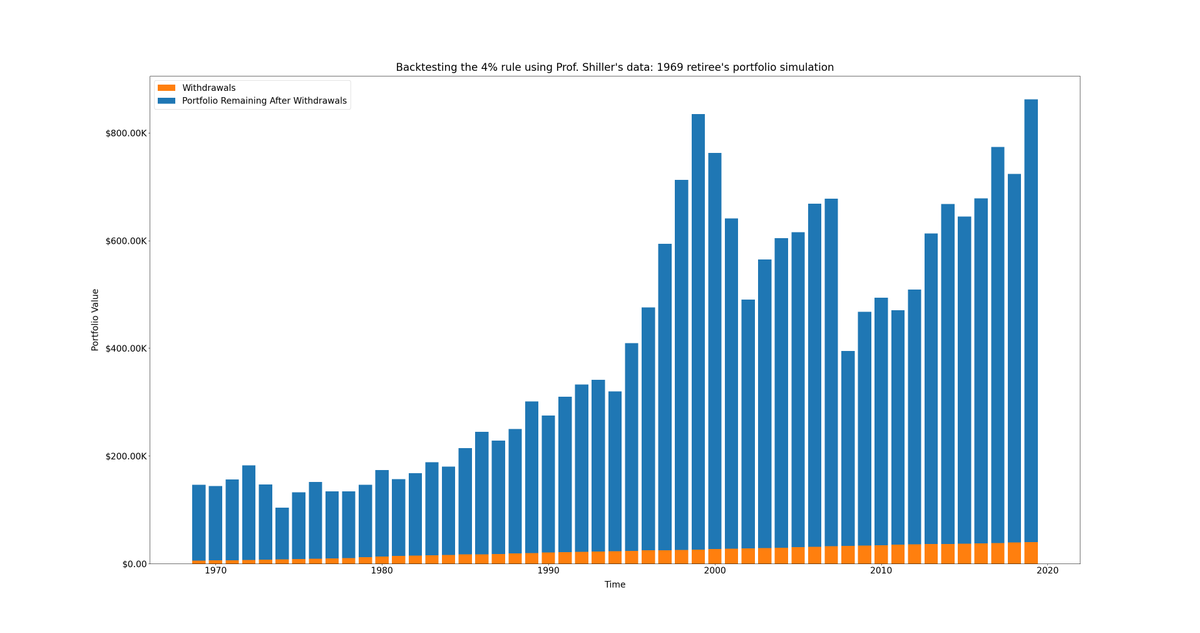

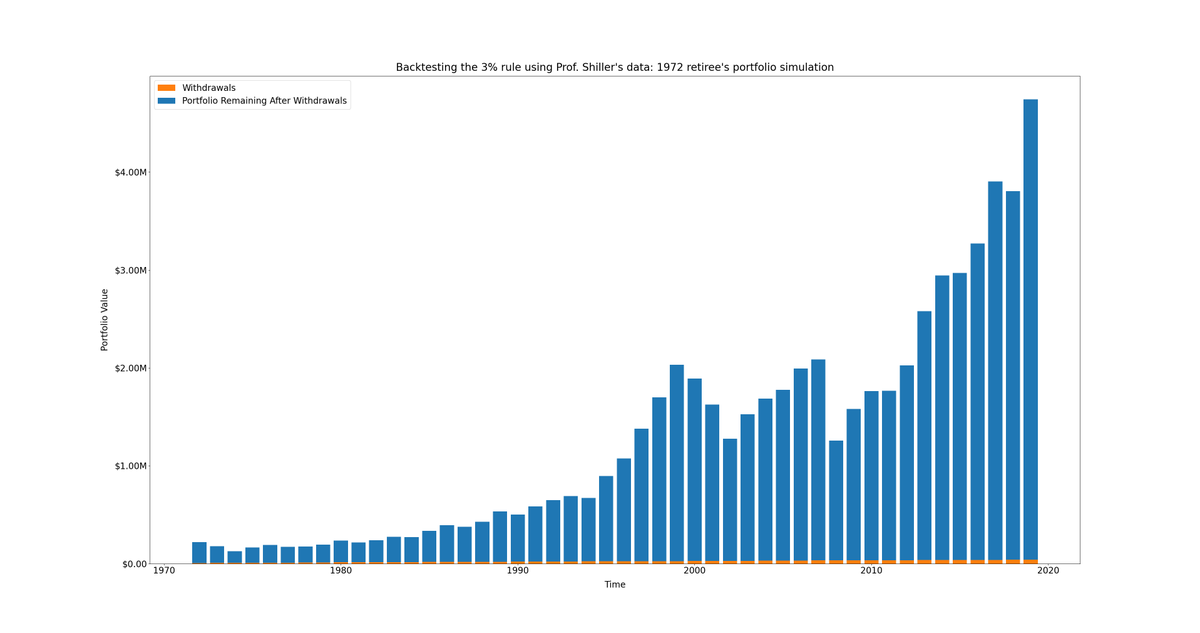

Imagine a guy named Joe who retired at the end of 1969 -- about 50 years ago.

Joe's annual expenses at the time were about $5,870. This is the equivalent of $40K now.

Following the 4% rule, Joe saved up a stock portfolio worth ~$147K in 1969. He then quit his job and retired.

Since 1969, at the end of each year, Joe would estimate his expenses for the next year (which would invariably be higher than the previous year due to inflation).

Joe would then withdraw this sum from his portfolio, leaving the rest to earn dividends and appreciate over time.

Some years, stocks would go up -- taking Joe's portfolio higher. Other years they would go down. But Joe kept his entire portfolio in stocks the entire time.

So that settles it, right?

The FIRE people are advocating for the 4% rule. Our own simulations -- both the steady (7%, 2%, 2%) scenario and the historical backtest since 1969 -- seem to agree.

So we can conclude that the 4% rule works, right?

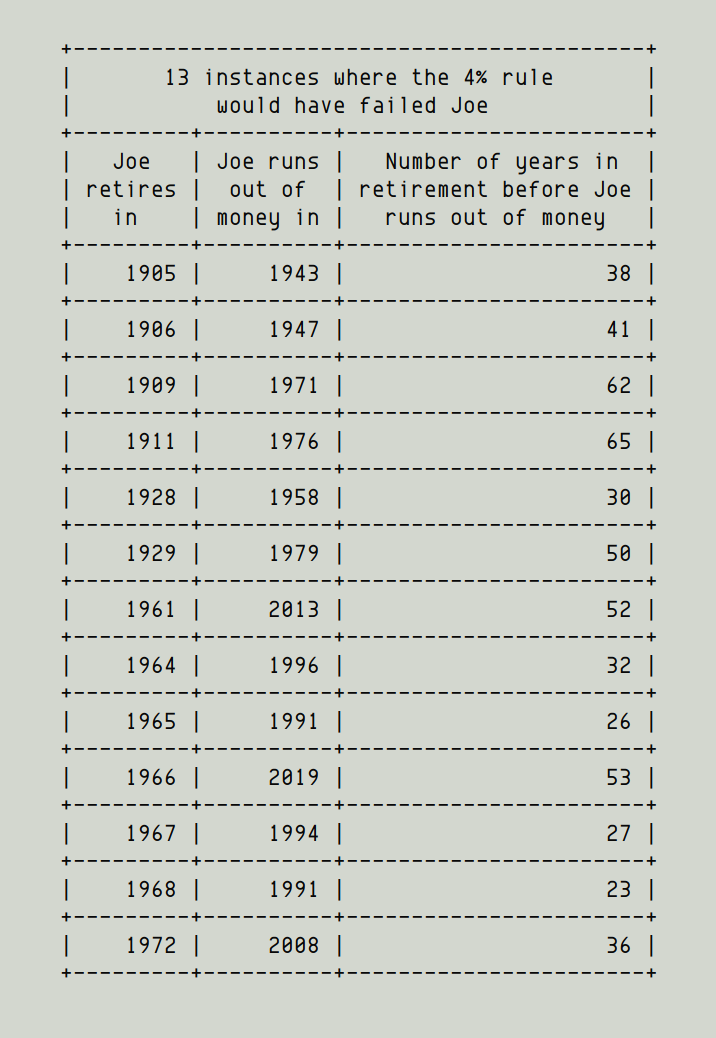

Again, not so fast.

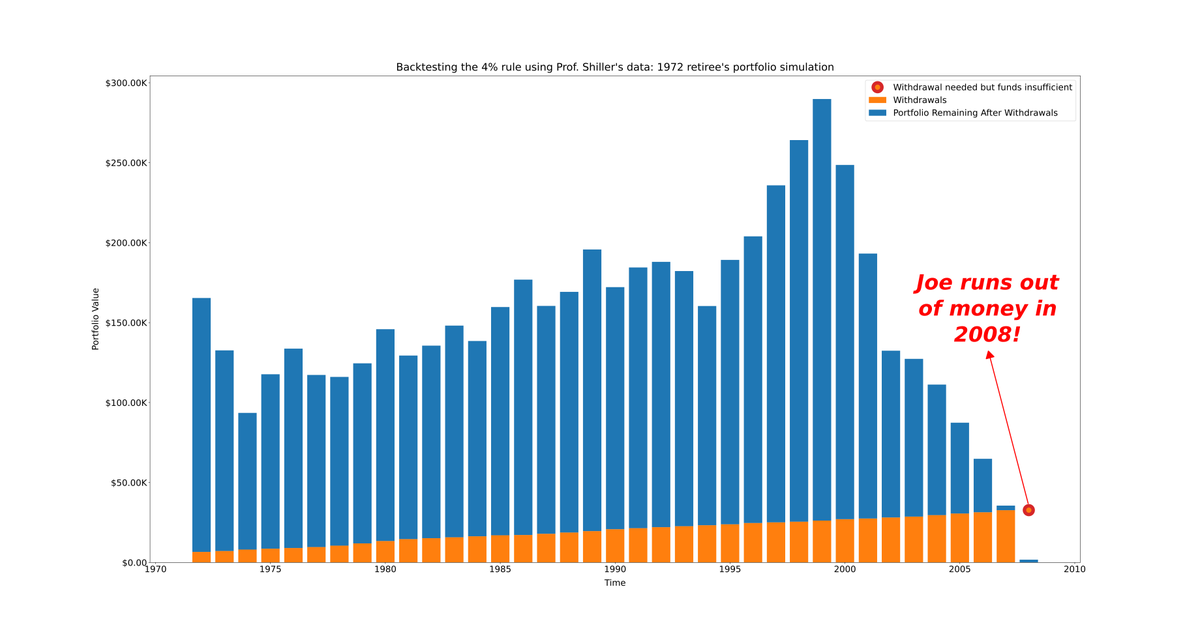

Key lesson: The early years of retirement are crucial. A combination of high inflation and poor portfolio performance in the early years can really hurt you and cause you to run out of money later on.

For example, when Joe retired in 1972, he did not know that a big stock market crash was coming in 1973 and 1974.

This crash, combined with inflation, caused Joe's withdrawals to creep up to higher and higher fractions of his portfolio -- until he was eventually bankrupted.

This is not to say that a 3% or better rule can never fail. It's just never failed in the past (or at least, as far as we backtested).

But of course, when we look to retire, we're planning for the *future*. Not the past.

So how do *we* decide which rule to follow?

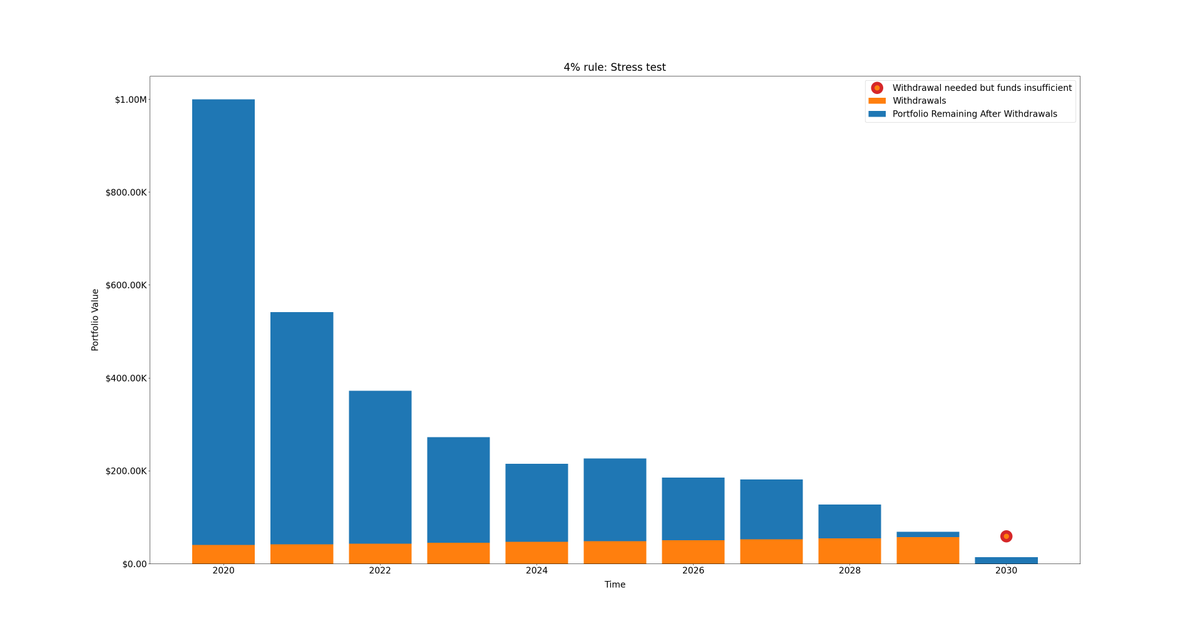

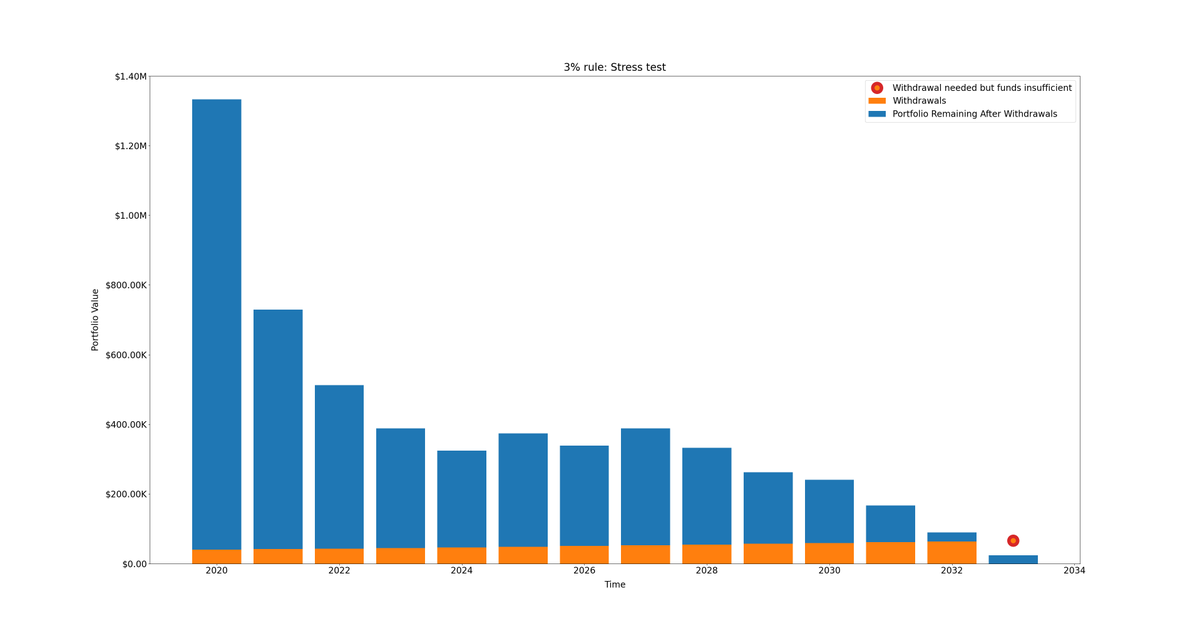

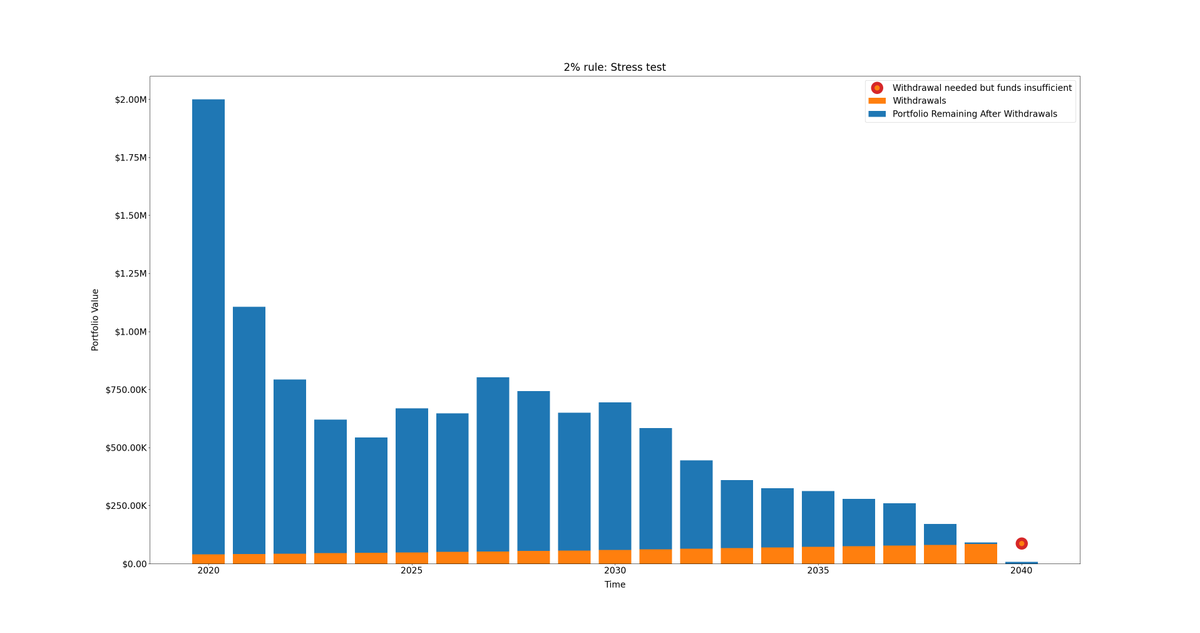

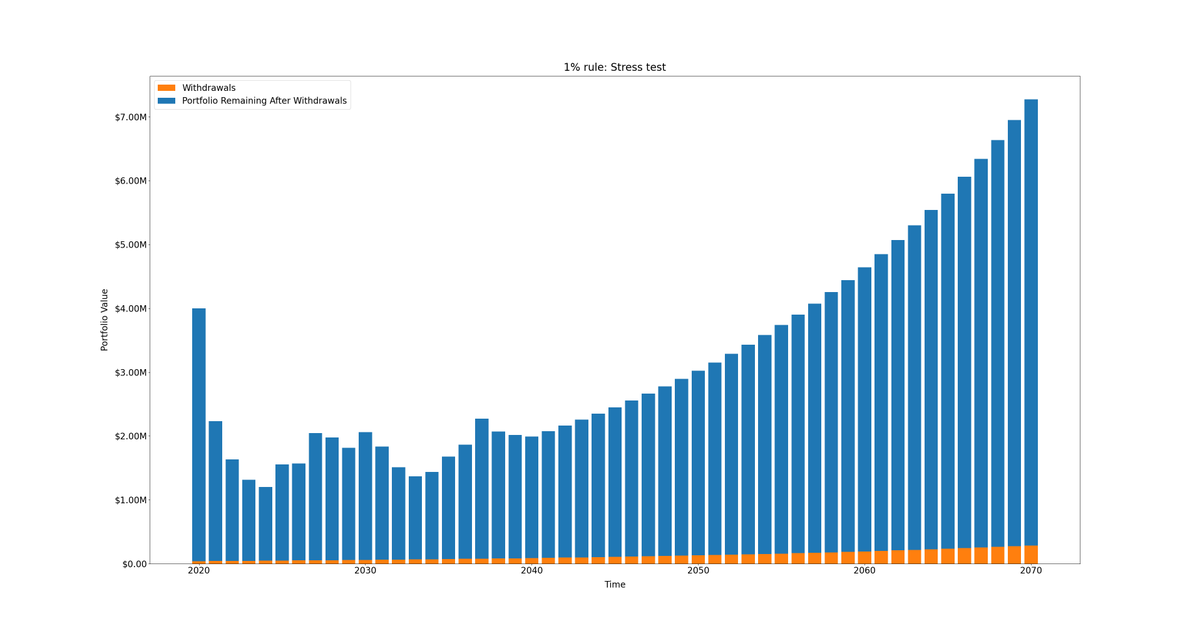

One approach is to run a "stress test".

This is an application of Charlie Munger's recommendation to "invert, always invert".

We figure out under what conditions we can run out of money in retirement. And then, which rule will not fail us even under those conditions.

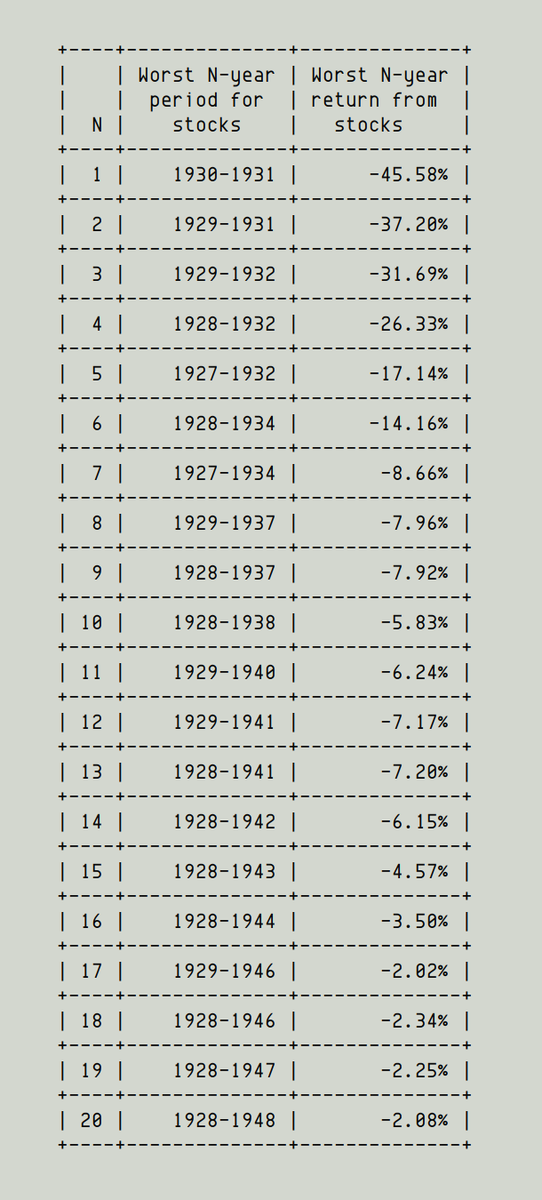

For our stress test, we'll assume that in our first year of retirement, stocks will deliver the worst 1-year return in history.

And in our first 2 years of retirement, they'll deliver the worst 2-year return in history.

And so on, for the first 20 years.

After 20 years, let's assume 7% steady returns (although we can be more conservative here as well).

And we'll assume a 2% dividend yield throughout.

Also, we know that the Fed wants to keep inflation at 2%. So we'll be conservative and assume that inflation will be 4%.

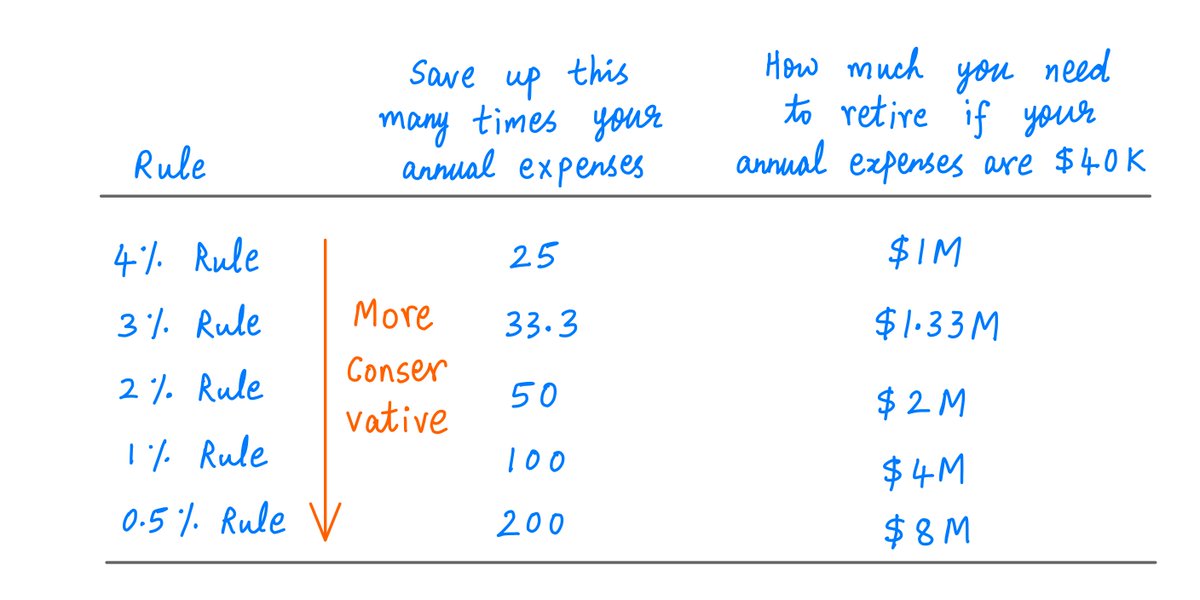

I'm a conservative person. So I like the 1% rule. This is also backed by our simple stress test.

But I do understand that the 1% rule is not easy: it requires saving up 4 times as much as the 4% rule advocates. This is a $4M portfolio for $40K in annual expenses.

But when it comes to retirement, it's far better to overshoot than undershoot.

You do not want to run out of money in old age.

And even if it turns out you've been too conservative, that's not so bad. You get to do more charity, leave more money to your kids, etc.

I'll leave you with some useful resources.

For anything related to the FIRE movement, @mrmoneymustache and @RootofGoodBlog are good accounts to follow.

I also like @rationalwalk, who sometimes posts about the pitfalls of the 4% rule.

@RobertJShiller has done a lot of great work on historical stock market performance, inflation, etc.

It's his data I used for running the backtests in this thread.

His book, Irrational Exuberance, is particularly good: amazon.com/Irrational-Exu…

And you can't beat Charlie Munger for general investing wisdom, weathering the volatility of stocks, the "invert" principle, and a very practical "bag of tricks", as he calls it in this Feb 2020 video (~1 hr, 12 mins):

Thanks for reading. Enjoy your weekend!

And all the very best for a wonderful retirement, free of financial worry.

/End