1/

Get a cup of coffee.

In this thread, I'll show you how to do a DCF analysis.

For those unfamiliar, DCF = Discounted Cash Flow.

Get a cup of coffee.

In this thread, I'll show you how to do a DCF analysis.

For those unfamiliar, DCF = Discounted Cash Flow.

2/

Imagine you live in a small town.

The town has a charming little bakery: Cakes N' Bakes.

Cakes N' Bakes has been in existence for 20 years. It's centrally located -- close to the town square. And it's run by your good friend Dave.

Imagine you live in a small town.

The town has a charming little bakery: Cakes N' Bakes.

Cakes N' Bakes has been in existence for 20 years. It's centrally located -- close to the town square. And it's run by your good friend Dave.

3/

One day, Dave invites you home for lunch.

Over lunch, Dave tells you that he's growing too old to run Cakes N' Bakes. He's been waking up at 4am and putting in 10 hour days for the last 20 years. Now he wants to relax a little and enjoy life.

One day, Dave invites you home for lunch.

Over lunch, Dave tells you that he's growing too old to run Cakes N' Bakes. He's been waking up at 4am and putting in 10 hour days for the last 20 years. Now he wants to relax a little and enjoy life.

4/

Dave knows you're always on the lookout for good investment opportunities. So he asks: would you be interested in buying Cakes N' Bakes from him?

You know Cakes N' Bakes is a good business. And you trust Dave. So you're definitely interested in this proposition.

Dave knows you're always on the lookout for good investment opportunities. So he asks: would you be interested in buying Cakes N' Bakes from him?

You know Cakes N' Bakes is a good business. And you trust Dave. So you're definitely interested in this proposition.

5/

So Dave gives you a copy of Cakes N' Bakes's financials for the last 20 years.

And he asks you to get back to him with a reasonable price that you'll be willing to pay for the business.

So Dave gives you a copy of Cakes N' Bakes's financials for the last 20 years.

And he asks you to get back to him with a reasonable price that you'll be willing to pay for the business.

6/

You take the financials home and study them.

As expected, they're not hard to understand.

This is a fairly simple business. You buy commodities (sugar, flour, etc.). You sell finished products (cupcakes, cookies, etc.) -- with a good profit margin built in.

You take the financials home and study them.

As expected, they're not hard to understand.

This is a fairly simple business. You buy commodities (sugar, flour, etc.). You sell finished products (cupcakes, cookies, etc.) -- with a good profit margin built in.

7/

Your main operating expenses will be raw materials (sugar, flour, etc.) and running the store (rent, electricity, employee salaries, etc.).

And from time to time, you'll incur capital expenses: upgrading your oven, your store decor and furniture, etc.

Your main operating expenses will be raw materials (sugar, flour, etc.) and running the store (rent, electricity, employee salaries, etc.).

And from time to time, you'll incur capital expenses: upgrading your oven, your store decor and furniture, etc.

8/

After accounting for all operating expenses, and after setting aside enough money for capital expenses, you figure that Cakes N' Bakes should generate about $1M for you, in cash, year after year.

After accounting for all operating expenses, and after setting aside enough money for capital expenses, you figure that Cakes N' Bakes should generate about $1M for you, in cash, year after year.

9/

This $1M is called "owner earnings". It's how much cash you, as the owner, can withdraw from the business each year without hurting the business's current or long term prospects.

For more details, here's my thread on how to calculate owner earnings:

This $1M is called "owner earnings". It's how much cash you, as the owner, can withdraw from the business each year without hurting the business's current or long term prospects.

For more details, here's my thread on how to calculate owner earnings:

https://twitter.com/10kdiver/status/1269305725357969409

10/

Having determined that the business will give you $1M in cash each year, the question now is: what should you pay for it?

You want to offer Dave a fair price. He's a good friend. You don't want to low-ball him.

At the same time, you want a good return for yourself.

Having determined that the business will give you $1M in cash each year, the question now is: what should you pay for it?

You want to offer Dave a fair price. He's a good friend. You don't want to low-ball him.

At the same time, you want a good return for yourself.

11/

Economists use a method called "Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) analysis" to answer questions like this.

The key idea behind a DCF is: the further out in the future a cash flow occurs, the less it's worth to you today.

Economists use a method called "Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) analysis" to answer questions like this.

The key idea behind a DCF is: the further out in the future a cash flow occurs, the less it's worth to you today.

12/

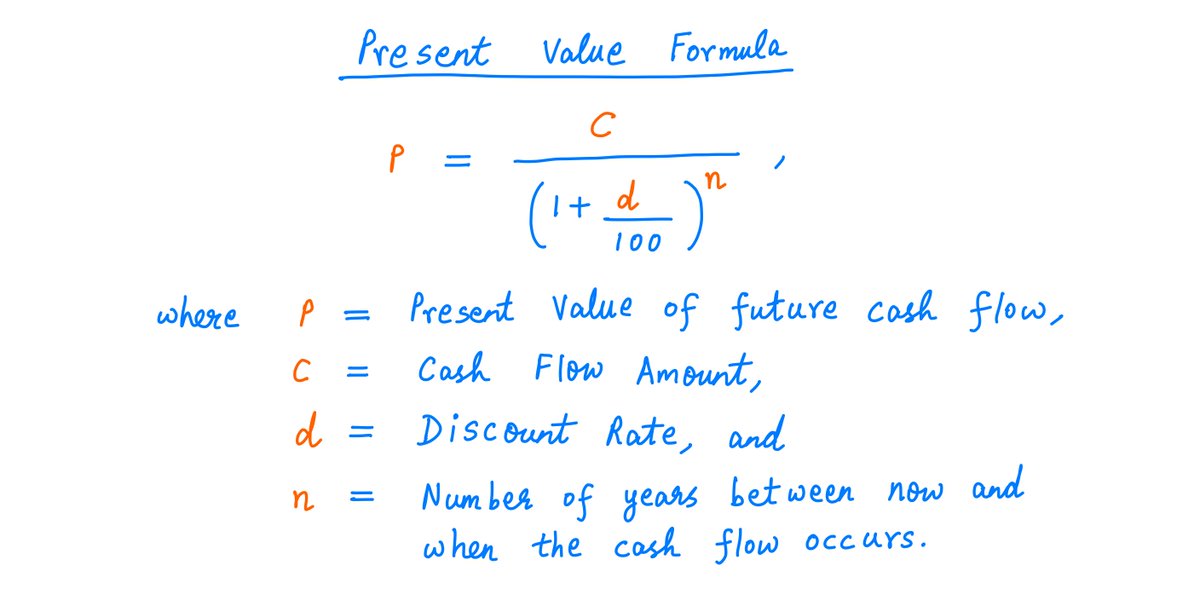

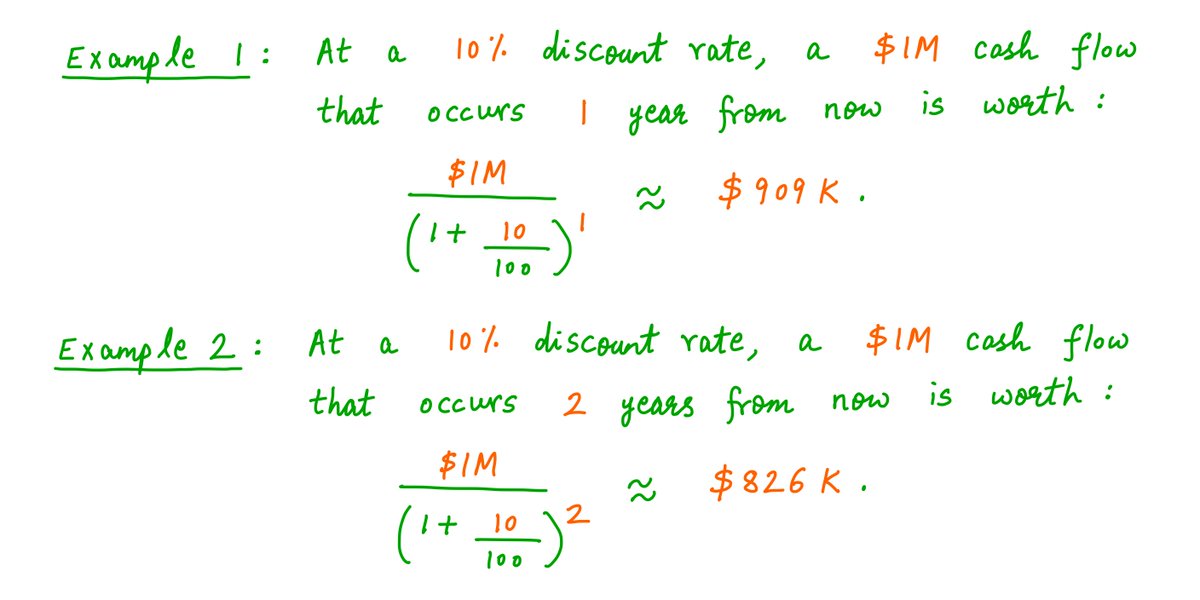

For example, a $1M cash payment that you'll get 1 year from now is perhaps worth ~$909K to you right now. There's a ~$91K "discount".

And the discount gets steeper as you extend the timeline further. The same $1M is worth only ~$826K if you get it in 2 years instead of 1.

For example, a $1M cash payment that you'll get 1 year from now is perhaps worth ~$909K to you right now. There's a ~$91K "discount".

And the discount gets steeper as you extend the timeline further. The same $1M is worth only ~$826K if you get it in 2 years instead of 1.

13/

Here's a formula to calculate the "present value" of a future cash flow, along with a couple examples.

As you can see, the formula takes a cash flow that occurs in the future, and "discounts" it to the present using a construct called the "discount rate": d% per year.

Here's a formula to calculate the "present value" of a future cash flow, along with a couple examples.

As you can see, the formula takes a cash flow that occurs in the future, and "discounts" it to the present using a construct called the "discount rate": d% per year.

14/

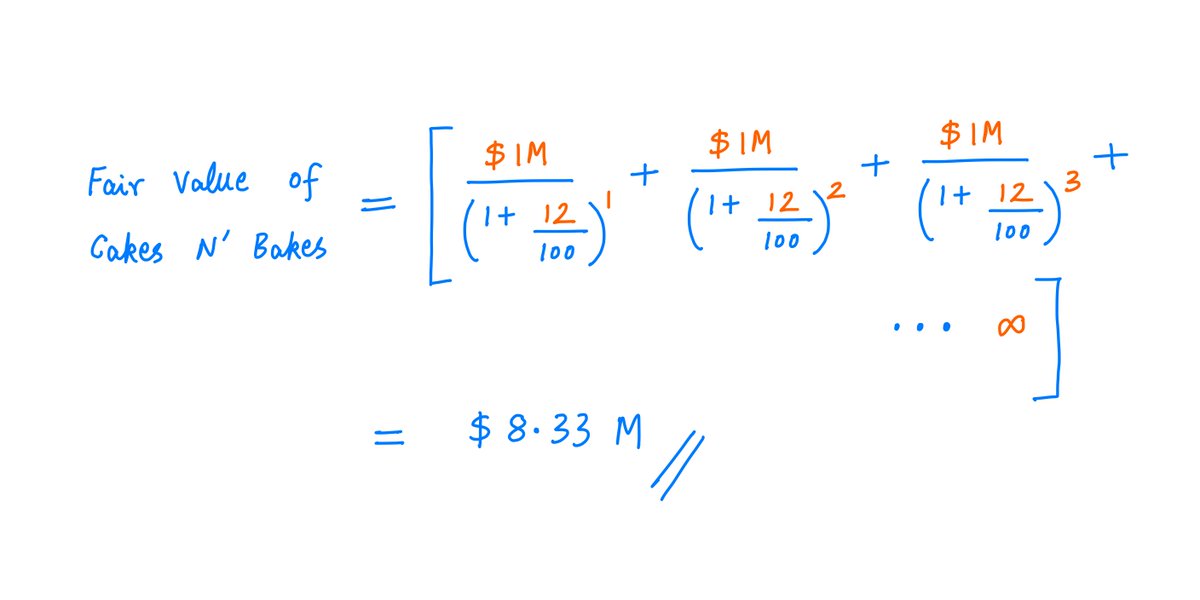

You can use this present value formula to calculate a fair price for Cakes N' Bakes.

Based on studying the financials, you expect this business to generate $1M cash for you each year.

Suppose you think it's fair to expect a 12% return on your investment.

You can use this present value formula to calculate a fair price for Cakes N' Bakes.

Based on studying the financials, you expect this business to generate $1M cash for you each year.

Suppose you think it's fair to expect a 12% return on your investment.

15/

Then the process is simple.

Just take all these $1M future cash flows, discount them all to the present using a 12% discount rate, and add up the present values.

That gives you an estimate of the fair value of Cakes N' Bakes -- which works out to about $8.33M:

Then the process is simple.

Just take all these $1M future cash flows, discount them all to the present using a 12% discount rate, and add up the present values.

That gives you an estimate of the fair value of Cakes N' Bakes -- which works out to about $8.33M:

16/

Key lesson 1: The fair value of a business is the sum of the present values of all future cash flows that the business can be expected to generate for its owner.

There's a "discount rate" deeply embedded in this calculation -- which should be chosen reasonably.

Key lesson 1: The fair value of a business is the sum of the present values of all future cash flows that the business can be expected to generate for its owner.

There's a "discount rate" deeply embedded in this calculation -- which should be chosen reasonably.

17/

Investors often use "P/E ratios" to judge whether businesses are overvalued or undervalued.

The P/E ratio of a business is its market price divided by its expected earnings over the next year.

DCF analysis can be used to find an appropriate P/E ratio for a business.

Investors often use "P/E ratios" to judge whether businesses are overvalued or undervalued.

The P/E ratio of a business is its market price divided by its expected earnings over the next year.

DCF analysis can be used to find an appropriate P/E ratio for a business.

18/

For example, our DCF analysis above yielded a fair price of $8.33M for Cakes N' Bakes.

Since Cakes N' Bakes is expected to earn $1M next year, a fair P/E ratio (as implied by our DCF analysis) is $8.33M/$1M = 8.33.

For example, our DCF analysis above yielded a fair price of $8.33M for Cakes N' Bakes.

Since Cakes N' Bakes is expected to earn $1M next year, a fair P/E ratio (as implied by our DCF analysis) is $8.33M/$1M = 8.33.

19/

Now, Cakes N' Bakes generates $1M annually -- but this $1M doesn't grow over time.

This isn't typical.

Typically, in addition to producing earnings, a business also gives you the option of reinvesting part of these earnings back into the business -- to grow it.

Now, Cakes N' Bakes generates $1M annually -- but this $1M doesn't grow over time.

This isn't typical.

Typically, in addition to producing earnings, a business also gives you the option of reinvesting part of these earnings back into the business -- to grow it.

20/

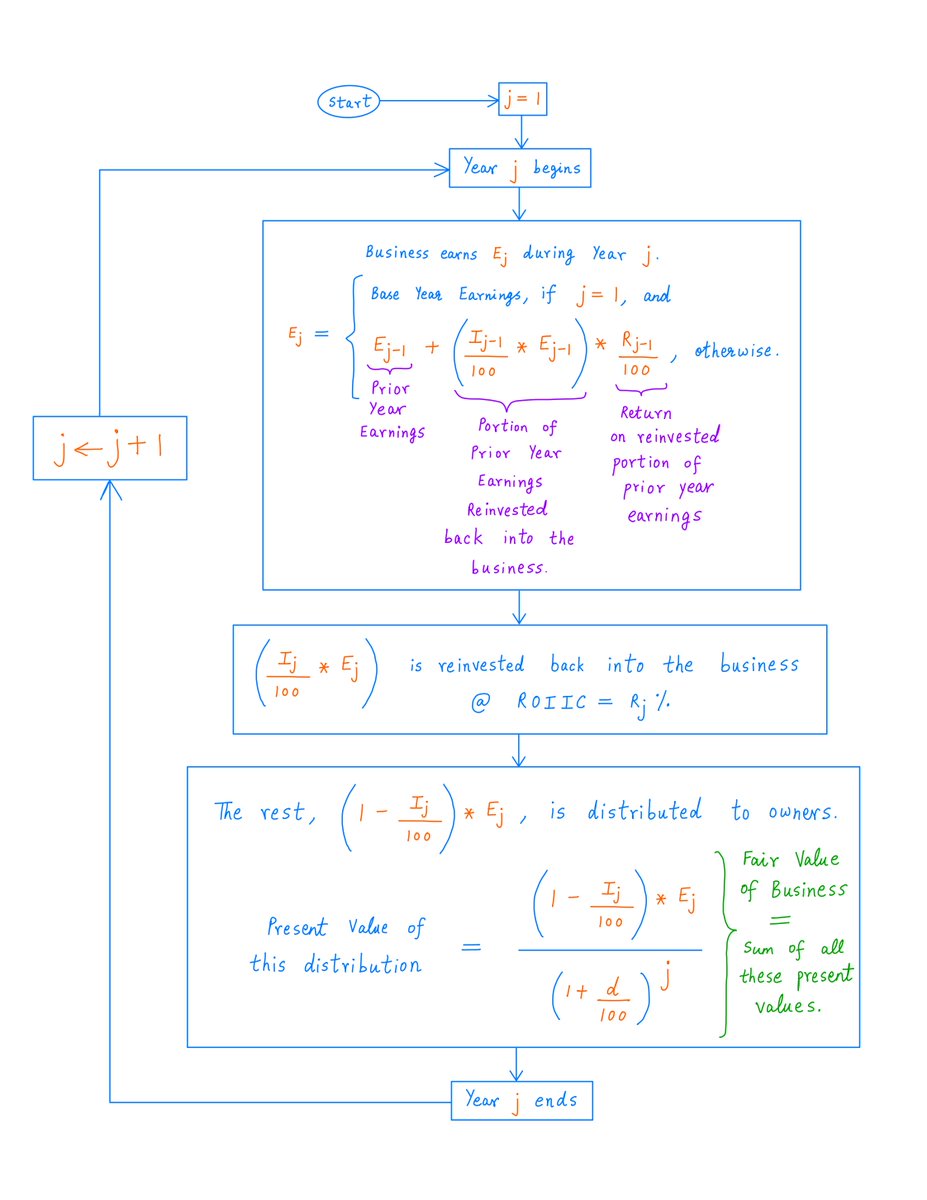

DCFs in such situations depend on 2 key factors (in addition to the discount rate):

(1) Reinvestment rate: the fraction of our earnings we reinvest back into the business each year, and

(2) ROIIC: the returns we get on such reinvested capital.

DCFs in such situations depend on 2 key factors (in addition to the discount rate):

(1) Reinvestment rate: the fraction of our earnings we reinvest back into the business each year, and

(2) ROIIC: the returns we get on such reinvested capital.

21/

For example, consider a business B2 (short for "Business 2").

Just like Cakes N' Bakes, B2 also produces $1M in earnings in Year 1.

But *unlike* Cakes N' Bakes, B2 allows us to reinvest 25% of earnings back into it at a 20% ROIIC each year.

How do we perform a DCF for B2?

For example, consider a business B2 (short for "Business 2").

Just like Cakes N' Bakes, B2 also produces $1M in earnings in Year 1.

But *unlike* Cakes N' Bakes, B2 allows us to reinvest 25% of earnings back into it at a 20% ROIIC each year.

How do we perform a DCF for B2?

22/

Well, in Year 1, B2 earns $1M.

Of this $1M, we reinvest 25% ($250K) back into B2, and withdraw the remaining 75% ($750K).

Thus, our cash flow for Year 1 is only $750K, not $1M.

At the 12% discount rate we used for Cakes N' Bakes, this $750K has a present value of ~$670K.

Well, in Year 1, B2 earns $1M.

Of this $1M, we reinvest 25% ($250K) back into B2, and withdraw the remaining 75% ($750K).

Thus, our cash flow for Year 1 is only $750K, not $1M.

At the 12% discount rate we used for Cakes N' Bakes, this $750K has a present value of ~$670K.

23/

In Year 2, B2 earns $1.05M -- the extra $50K being the 20% ROIIC on the $250K we reinvested in Year 1.

Again, we reinvest 25% ($262.5K) and withdraw 75% ($787.5K, with present value ~$628K).

As before, we just add up these present values to arrive at a fair value for B2.

In Year 2, B2 earns $1.05M -- the extra $50K being the 20% ROIIC on the $250K we reinvested in Year 1.

Again, we reinvest 25% ($262.5K) and withdraw 75% ($787.5K, with present value ~$628K).

As before, we just add up these present values to arrive at a fair value for B2.

24/

Here's a flowchart with all the formulas you need to do such DCFs.

The flowchart assumes that in Year j, I_{j}% of earnings is reinvested at R_{j}% ROIIC. So, both reinvestment rate and ROIIC can vary from year to year. The discount rate is d% per year.

Here's a flowchart with all the formulas you need to do such DCFs.

The flowchart assumes that in Year j, I_{j}% of earnings is reinvested at R_{j}% ROIIC. So, both reinvestment rate and ROIIC can vary from year to year. The discount rate is d% per year.

25/

Following the DCF flowchart, the fair value of B2 works out to ~$10.71M -- about 29% higher than the fair value of Cakes N' Bakes ($8.33M) at the same 12% discount rate.

That's the power of being able to reinvest earnings back into the business at a sufficiently high ROIIC.

Following the DCF flowchart, the fair value of B2 works out to ~$10.71M -- about 29% higher than the fair value of Cakes N' Bakes ($8.33M) at the same 12% discount rate.

That's the power of being able to reinvest earnings back into the business at a sufficiently high ROIIC.

26/

In fact, higher the ROIIC, greater the fair value.

For example, as ROIIC increases from 20% to 40%, B2's fair value goes up from ~$10.71M to ~$37.5M -- for the same 25% reinvestment rate and 12% discount rate.

The flip side is: as ROIIC decreases, so does fair value.

In fact, higher the ROIIC, greater the fair value.

For example, as ROIIC increases from 20% to 40%, B2's fair value goes up from ~$10.71M to ~$37.5M -- for the same 25% reinvestment rate and 12% discount rate.

The flip side is: as ROIIC decreases, so does fair value.

27/

Key lesson 2: Not all reinvestment funded growth is intelligent.

If reinvestment is possible only at ROIICs below the discount rate, a business owner is better off withdrawing earnings than reinvesting them.

Key lesson 2: Not all reinvestment funded growth is intelligent.

If reinvestment is possible only at ROIICs below the discount rate, a business owner is better off withdrawing earnings than reinvesting them.

28/

For example, at a 5% ROIIC and a 12% discount rate, fair value for B2 is only ~$7M at a 25% reinvestment rate.

This is ~16% *lower* than the fair value of ~$8.33M that's realizable if all earnings are withdrawn rather than reinvested at such a low ROIIC.

For example, at a 5% ROIIC and a 12% discount rate, fair value for B2 is only ~$7M at a 25% reinvestment rate.

This is ~16% *lower* than the fair value of ~$8.33M that's realizable if all earnings are withdrawn rather than reinvested at such a low ROIIC.

29/

Also, just as trees don't grow to the sky, businesses don't grow at high ROIICs forever.

For this reason, DCFs typically use "terminal" assumptions.

That is, ROIICs are assumed to be high only up to a certain time in the future -- say, 15 years out.

Also, just as trees don't grow to the sky, businesses don't grow at high ROIICs forever.

For this reason, DCFs typically use "terminal" assumptions.

That is, ROIICs are assumed to be high only up to a certain time in the future -- say, 15 years out.

30/

After this, it's assumed that reinvestment opportunities will be limited.

So, up to this point, a substantial portion of earnings may be reinvested. But after this, most/all earnings will be withdrawn rather than reinvested.

After this, it's assumed that reinvestment opportunities will be limited.

So, up to this point, a substantial portion of earnings may be reinvested. But after this, most/all earnings will be withdrawn rather than reinvested.

31/

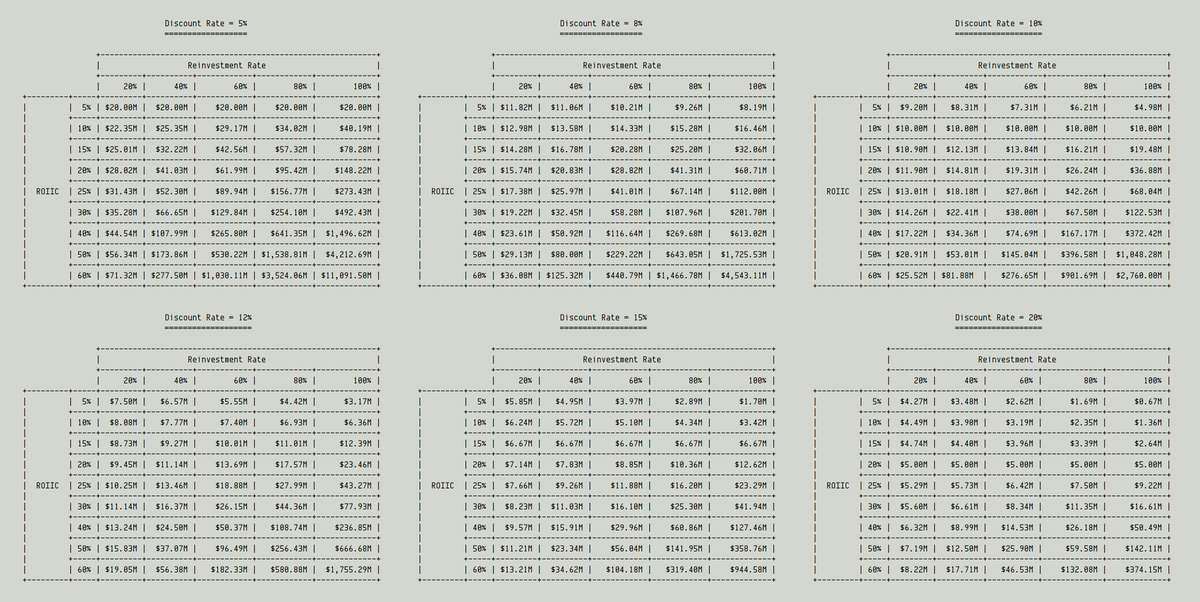

The tables below show the fair value of B2 calculated via DCFs for various discount rates, reinvestment rates, and ROIICs.

In each case, reinvestments at ROIIC are done for 15 years. After this, reinvestments are stopped and all further earnings are completely withdrawn.

The tables below show the fair value of B2 calculated via DCFs for various discount rates, reinvestment rates, and ROIICs.

In each case, reinvestments at ROIIC are done for 15 years. After this, reinvestments are stopped and all further earnings are completely withdrawn.

32/

Some key points from the tables above:

First, as ROIIC increases, so does fair value.

Second, as the reinvestment rate increases, fair value {increases, does not change, or decreases} depending on whether ROIIC is {greater than, equal to, or less than} the discount rate.

Some key points from the tables above:

First, as ROIIC increases, so does fair value.

Second, as the reinvestment rate increases, fair value {increases, does not change, or decreases} depending on whether ROIIC is {greater than, equal to, or less than} the discount rate.

33/

Third, fair value always decreases as the discount rate increases.

Fourth, fair values produced by DCFs can be *highly* sensitive to discount rates, especially when reinvestment rates and ROIICs are both high.

Third, fair value always decreases as the discount rate increases.

Fourth, fair values produced by DCFs can be *highly* sensitive to discount rates, especially when reinvestment rates and ROIICs are both high.

34/

For example, at 50% ROIIC and 100% reinvestment, increasing the discount rate by just 2% (from 10% to 12%) is enough to cause fair value to drop 36% -- from ~$1,048M to ~$667M.

For example, at 50% ROIIC and 100% reinvestment, increasing the discount rate by just 2% (from 10% to 12%) is enough to cause fair value to drop 36% -- from ~$1,048M to ~$667M.

35/

This is why it's so difficult to value SaaS companies via DCFs. These companies tend to reinvest all their earnings -- and usually report high ROIICs.

This is why it's so difficult to value SaaS companies via DCFs. These companies tend to reinvest all their earnings -- and usually report high ROIICs.

https://twitter.com/BillBrewsterSCG/status/1261650658949824512?s=20

36/

Because DCFs can be highly sensitive to input parameters, people often use them to justify absurd valuations.

Just tweak the discount rate and ROIIC, extend the timeline out to 20 years instead of 15 -- and the market price suddenly looks very reasonable.

Beware!

Because DCFs can be highly sensitive to input parameters, people often use them to justify absurd valuations.

Just tweak the discount rate and ROIIC, extend the timeline out to 20 years instead of 15 -- and the market price suddenly looks very reasonable.

Beware!

37/

As usual, I'll leave you with a few useful references.

Buffett's 1986 letter to shareholders contains a wonderful discussion of owner earnings -- the main source of cash flows that go into a DCF.

berkshirehathaway.com/letters/1986.h…

As usual, I'll leave you with a few useful references.

Buffett's 1986 letter to shareholders contains a wonderful discussion of owner earnings -- the main source of cash flows that go into a DCF.

berkshirehathaway.com/letters/1986.h…

38/

Michael Mauboussin (@mjmauboussin) has a very nice article titled "The Math of Value And Growth", which served as inspiration for this thread. For example, I derived the DCF flowchart above mostly from the descriptions in the article.

morganstanley.com/im/publication…

Michael Mauboussin (@mjmauboussin) has a very nice article titled "The Math of Value And Growth", which served as inspiration for this thread. For example, I derived the DCF flowchart above mostly from the descriptions in the article.

morganstanley.com/im/publication…

39/

Also, @borrowed_ideas has written a thoughtful post about the difficulties of valuing SaaS companies using DCFs:

borrowedideas.substack.com/p/is-valuing-s…

Also, @borrowed_ideas has written a thoughtful post about the difficulties of valuing SaaS companies using DCFs:

borrowedideas.substack.com/p/is-valuing-s…

40/

If you've gotten this far, you have superhuman levels of determination and perseverance. Kudos!

Thanks for reading. Enjoy your weekend!

/End

If you've gotten this far, you have superhuman levels of determination and perseverance. Kudos!

Thanks for reading. Enjoy your weekend!

/End

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh