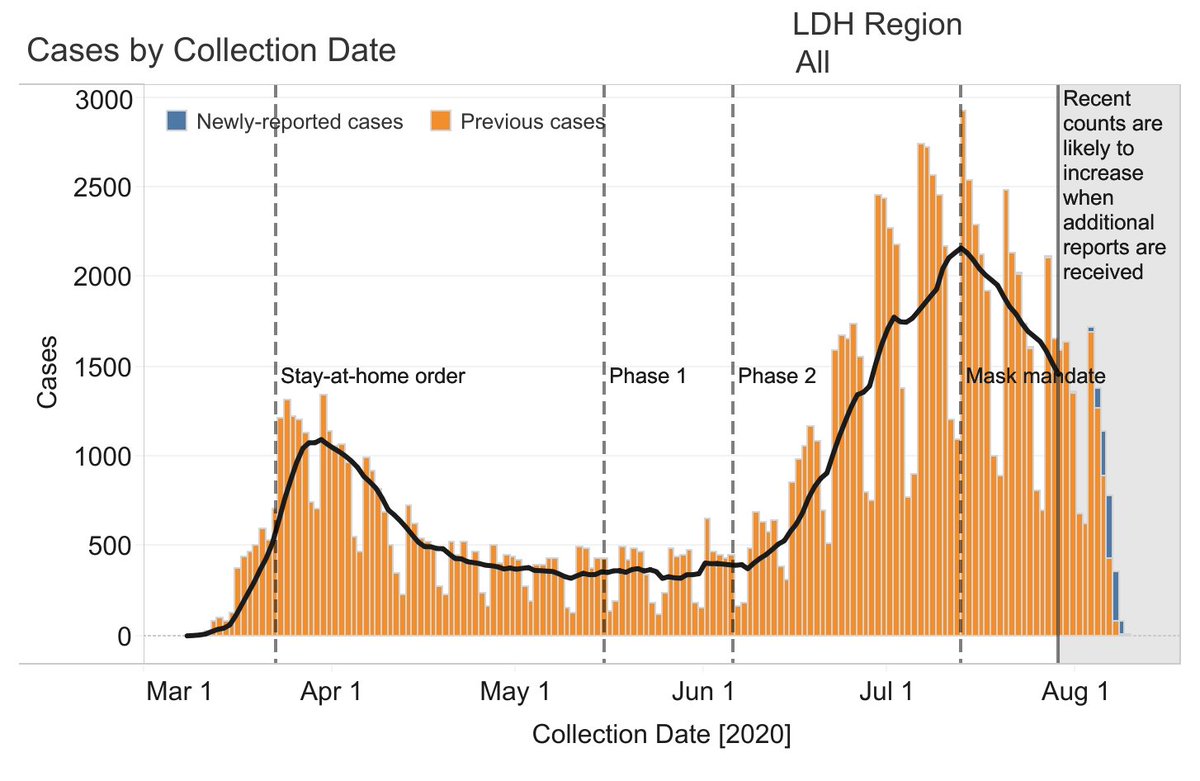

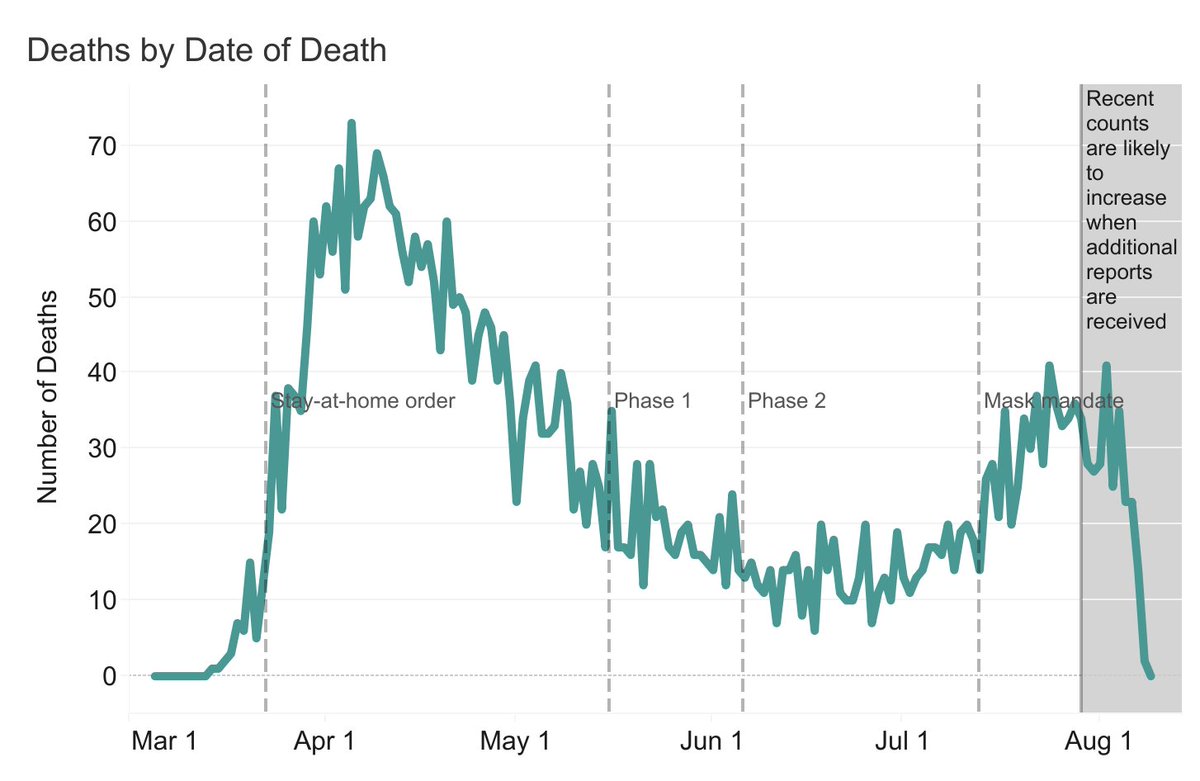

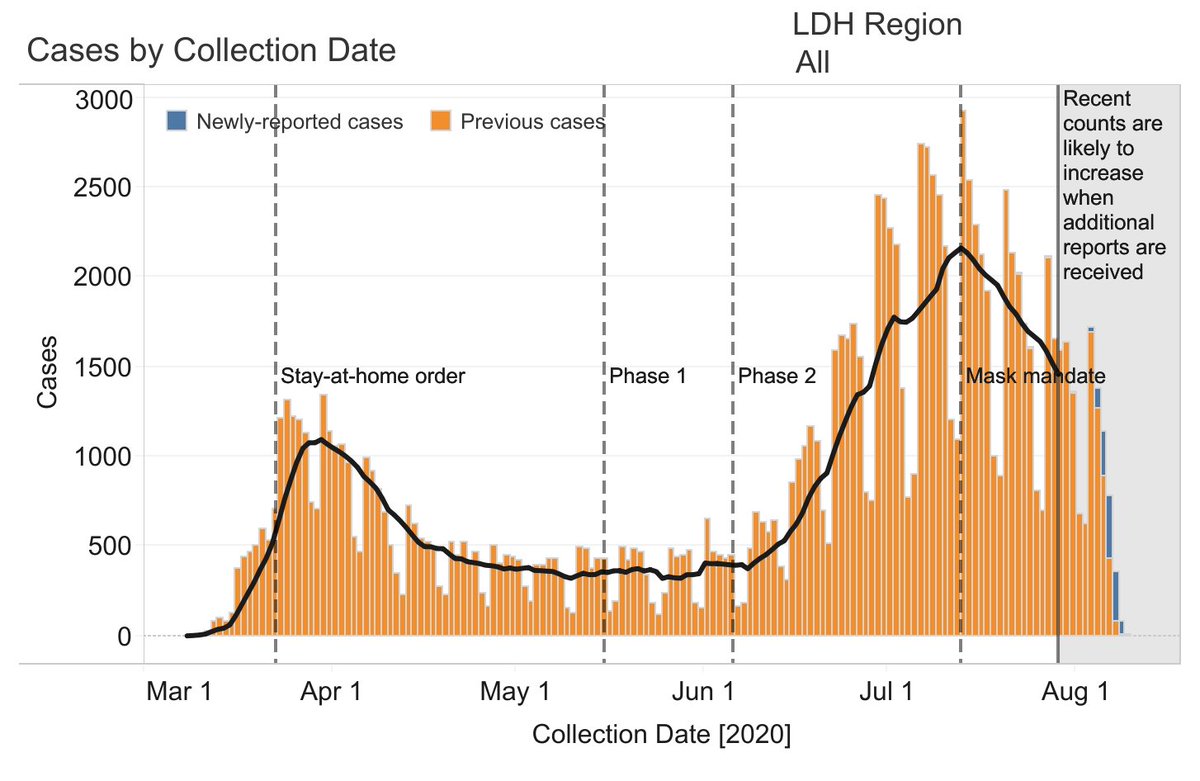

Louisiana is a good case study because it's the only state that had two significant waves affecting a large proportion of its population.

Here's a closer look.

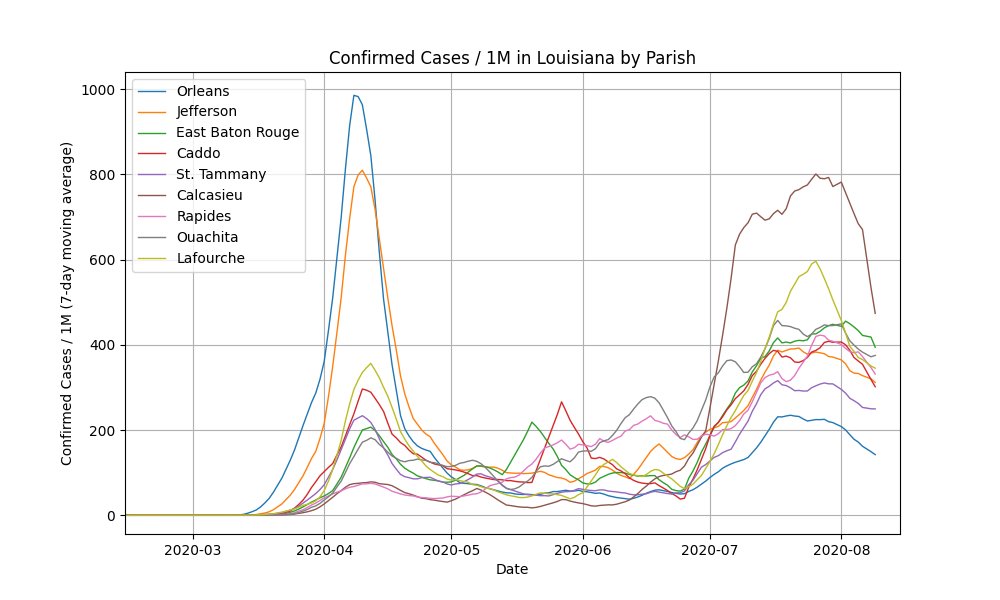

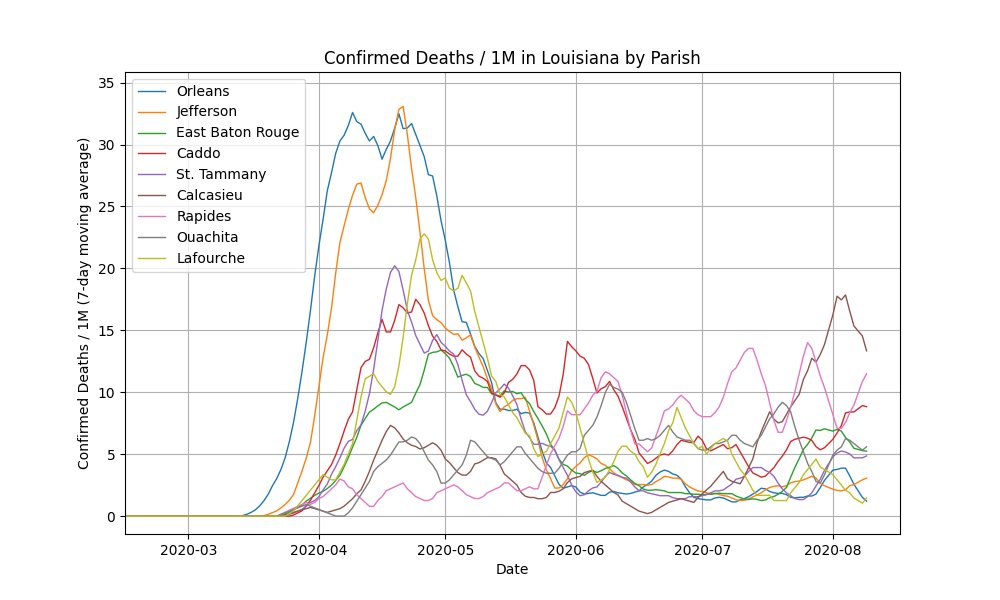

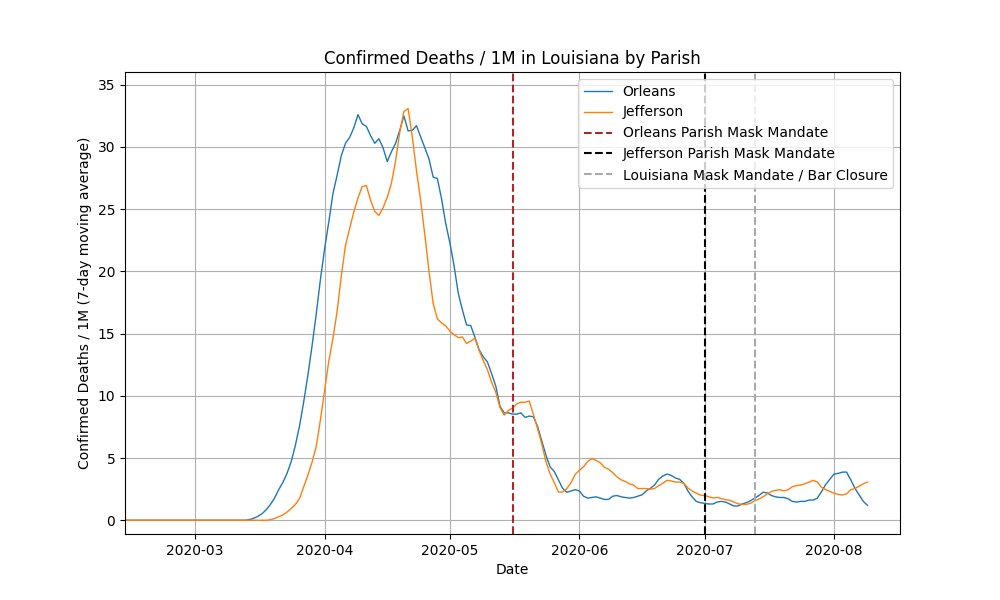

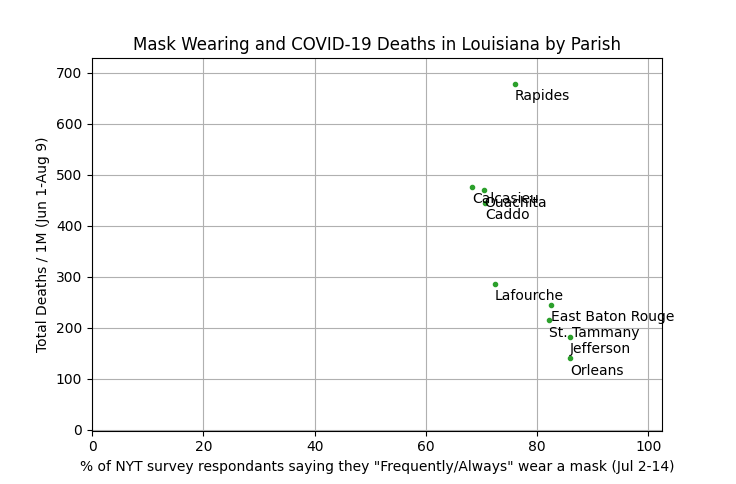

But if you break it down by parishes (counties), the data tells a different story.

Plots source: @LADeptHealth

A piece on this by @dwallacewells:

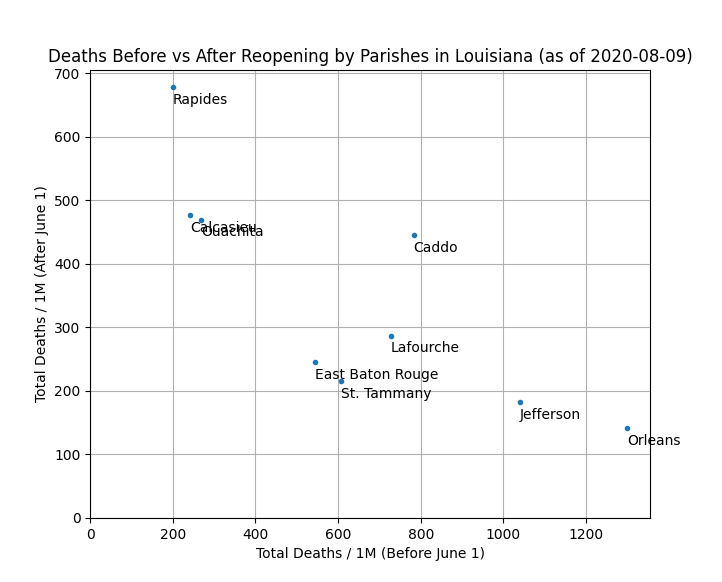

But the current data does not corroborate that theory, at least not in Louisiana.

Plot source: @LADeptHealth

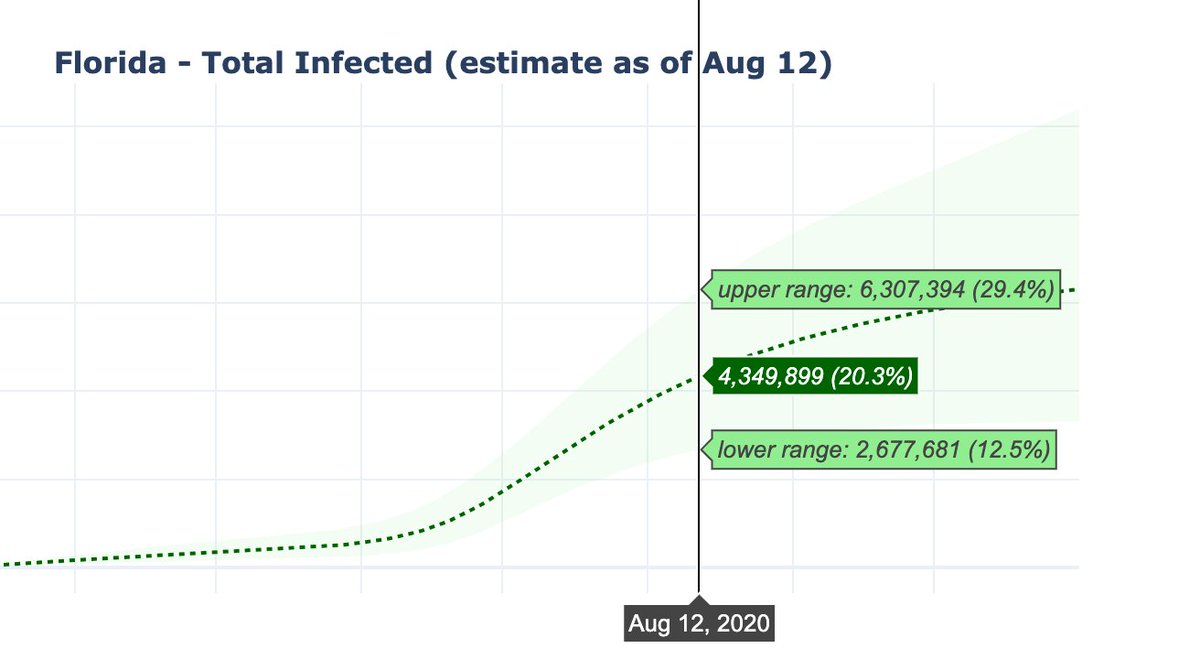

But the difference b/w the highest and lowest is not large (18%).

h/t @Crimealytics

More discussion from last week:

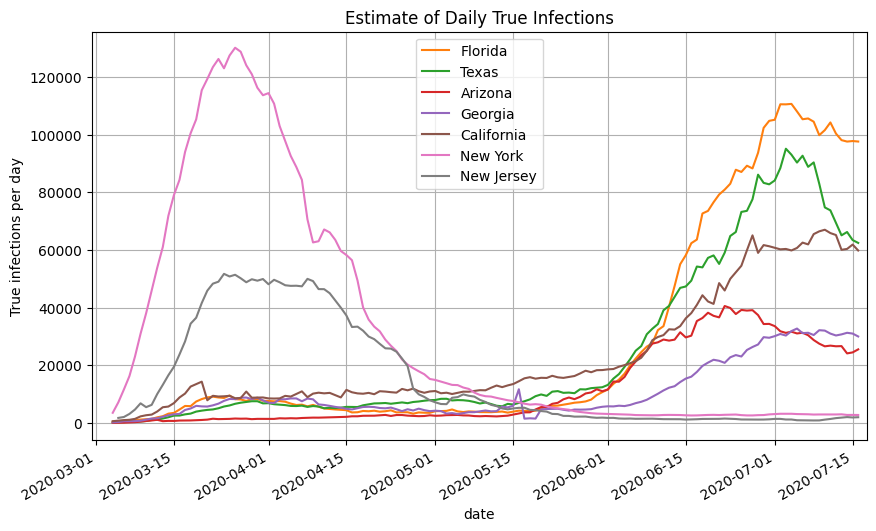

Now, we're seeing more widespread praise for all of the interventions that were put in place.

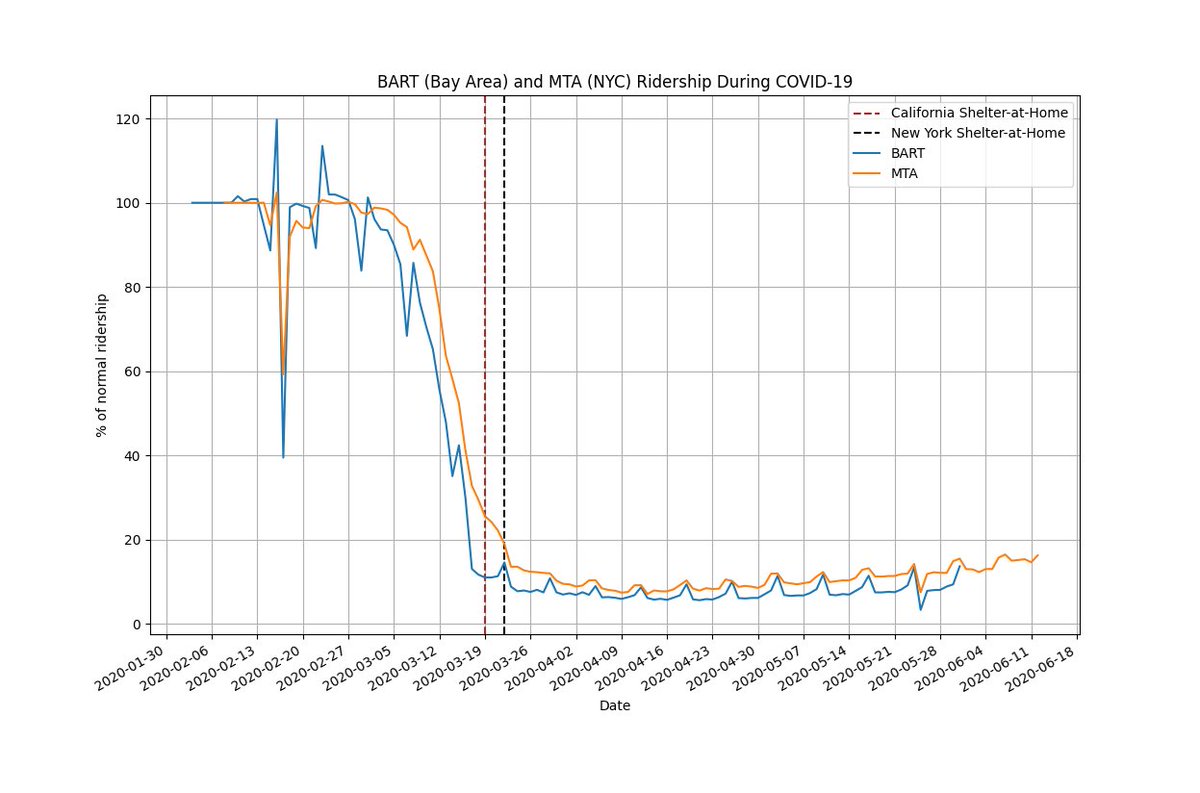

But the level of intervention did not change.

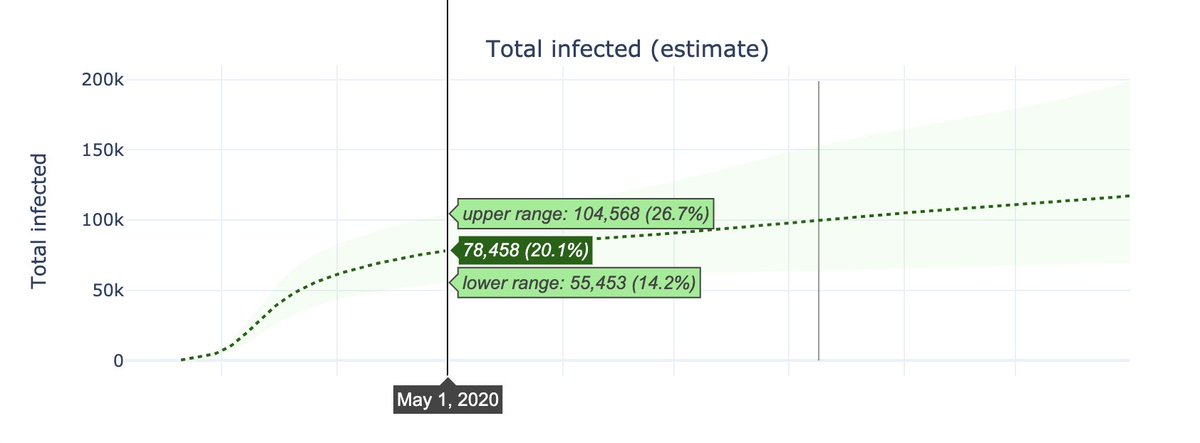

It was voluntarily human behavior that began more than two weeks prior (see graph). The lockdown helped.

Graph source: github.com/youyanggu/subw…

It may cause people to think that the interventions are enough to return to normal, when you likely also need behavior changes + immunity.

Caveat #2: From a statistical perspective, it is difficult to disentangle population immunity from behavior changes, because the two variables are likely collinear.

If society were to "return to normal", then the effects of such immunity would be significantly reduced as the rate of transmission increases.

Caveat #5: I presented an example using data from Louisiana, but it may not be representative of the entire US.

Caveat #7: I apologize in advance if I said anything inaccurate. Please let me know and I will correct it.

Anecdotal evidence can be useful. But if the data does not support the anecdotal evidence, we have a responsibility as scientists to adjust our priors.

To conclude, I think we should be careful in attributing causations behind recent declines in cases when they are merely correlations. We cannot cut corners, even if it's a means to an end.

More research is needed.