Get a cup of coffee.

In this thread, I'll help you decide whether you need a fund manager (and if so, how to choose one).

Imagine that you're an architect.

You have clients all over the country -- wealthy individuals, companies, even government bodies. They hire you to design their homes, offices, stores, hotels -- you name it.

It's a very fulfilling life.

You love architecture. You're good at it. You're paid well. And you have a positive impact on the world: people value and cherish your designs.

But it's a busy life.

You have very little free time.

And you don't want to spend this free time researching stocks and studying financial statements.

So, you have a large and growing pile of savings, but no idea how to invest it.

You generally have two choices in this situation:

The "passive" choice: Invest your savings in a diversified low-cost index fund (like Vanguard's S&P 500 index fund, $VOO).

The "active" choice: Find a fund manager, and trust them to invest your savings wisely.

With the "passive" choice, your savings will compound at the "market" rate of return.

Historically, in the US, this has been about 7% per year, plus maybe 2% in dividends.

Assuming you reinvest dividends back into the same low-cost index fund, let's call it 9% per year.

With the "active" choice, you have a lot riding on your fund manager.

They may be able to get you a "better than market" rate of return, but they're also going to charge you fees.

What matters, of course, is the return you get *after* paying these fees.

So, what do these fees look like?

Well, different fund managers use different fee structures.

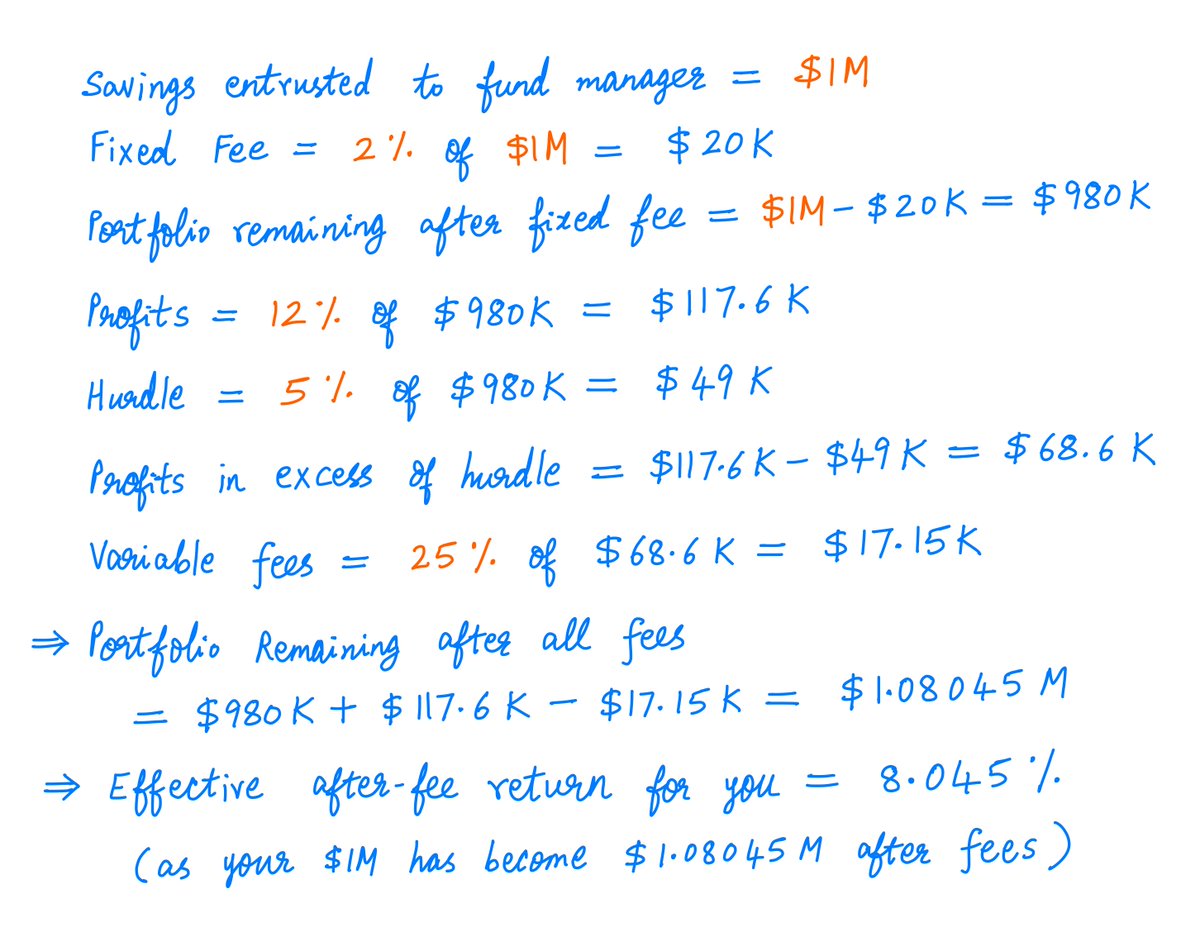

But most fee structures have 3 parameters in common: a fixed component (F%), a variable component (V%), and a hurdle rate (H%).

It works like this:

At the start of each year, the fund manager takes out F% of your portfolio as "fixed" fees.

The rest, (100 - F)%, grows during the year -- producing profits.

At year end, the fund manager takes V% of all profits in excess of the hurdle rate (H%).

In the example above, your fund manager picked stocks that went up 12%. But *you* only ended up with ~8%.

Why? Because the rest went towards paying the fund manager's fees.

This is the problem when you go "active". Fees can eat up big chunks of your returns.

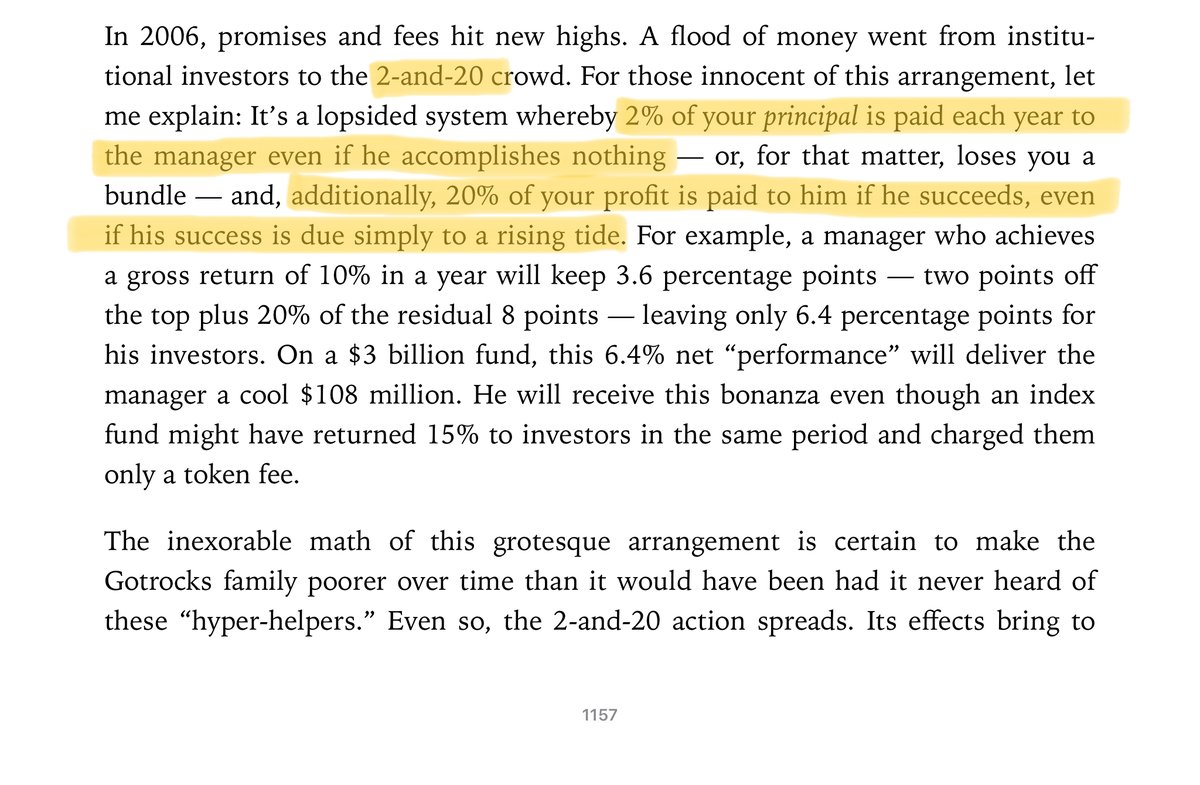

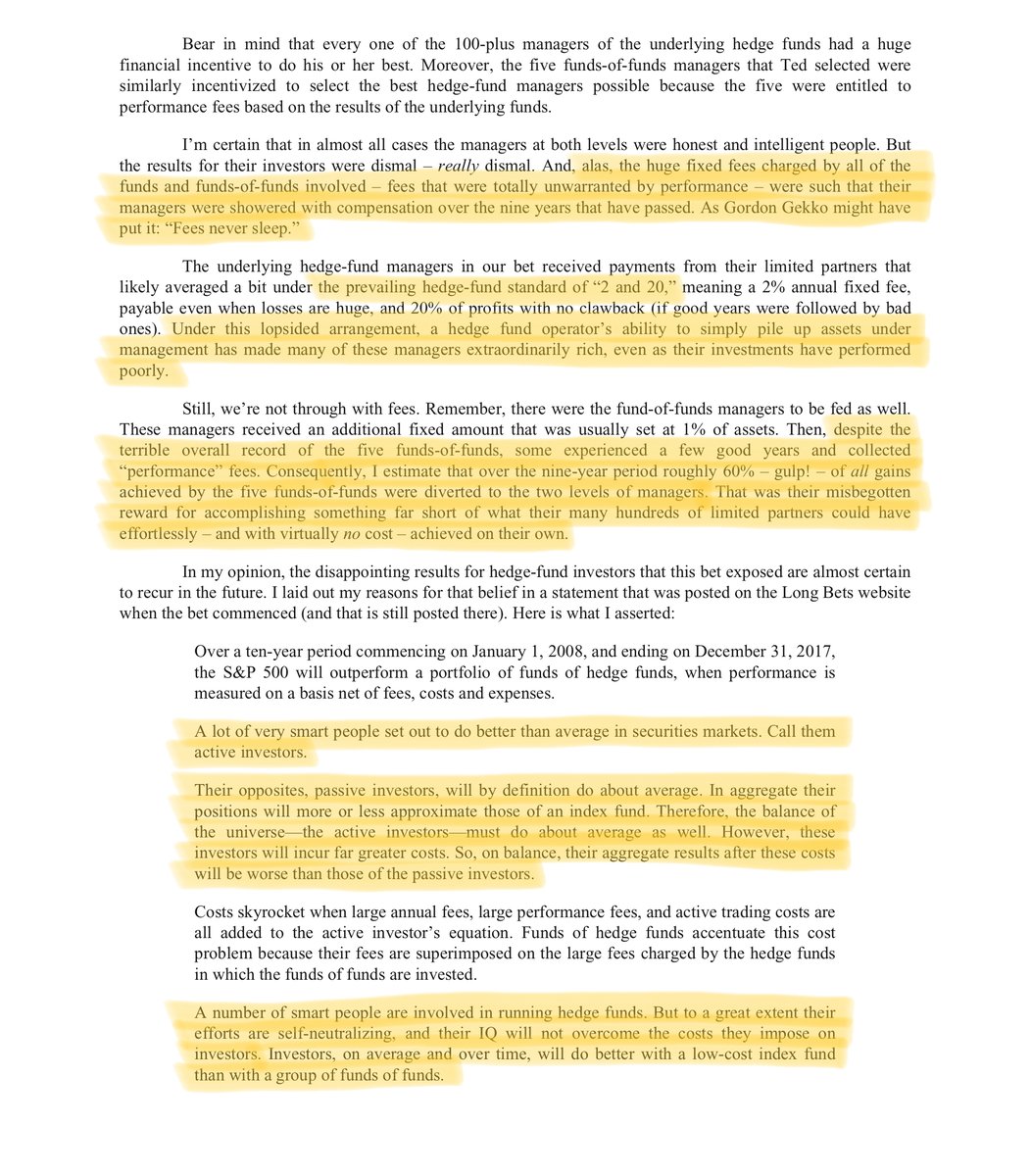

For example, many fund managers charge "2 and 20". This means a 2% fixed fee plus 20% of all profits -- no hurdle.

This has become "standard" on Wall Street.

In our terminology, this is {F, V, H} = {2, 20, 0}.

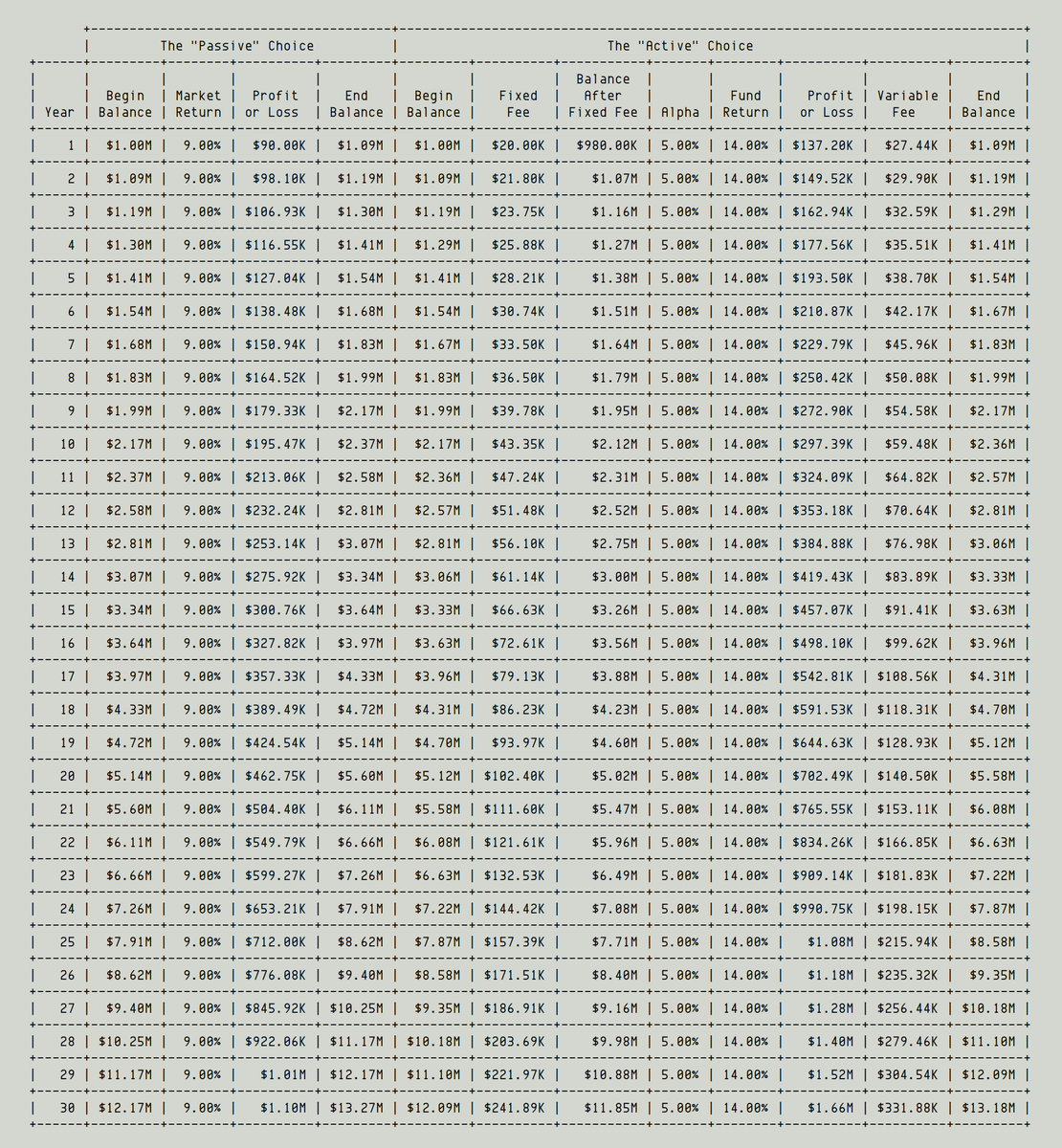

Let's say the market will return 9% over the next 30 years.

Also, let's say you know a really bright fund manager, Chris.

Chris is capable of "5% alpha". That is, Chris's stock picks will return 14% over the next 30 years.

But Chris charges "2 and 20".

Thus, even a stellar fund manager -- who achieves a steady 5% alpha over 30 years -- cannot compensate for a punitive "2 and 20" fee structure.

The fund manager's alpha should be higher, or his fees lower. Otherwise, his clients are better off with a low-cost index fund.

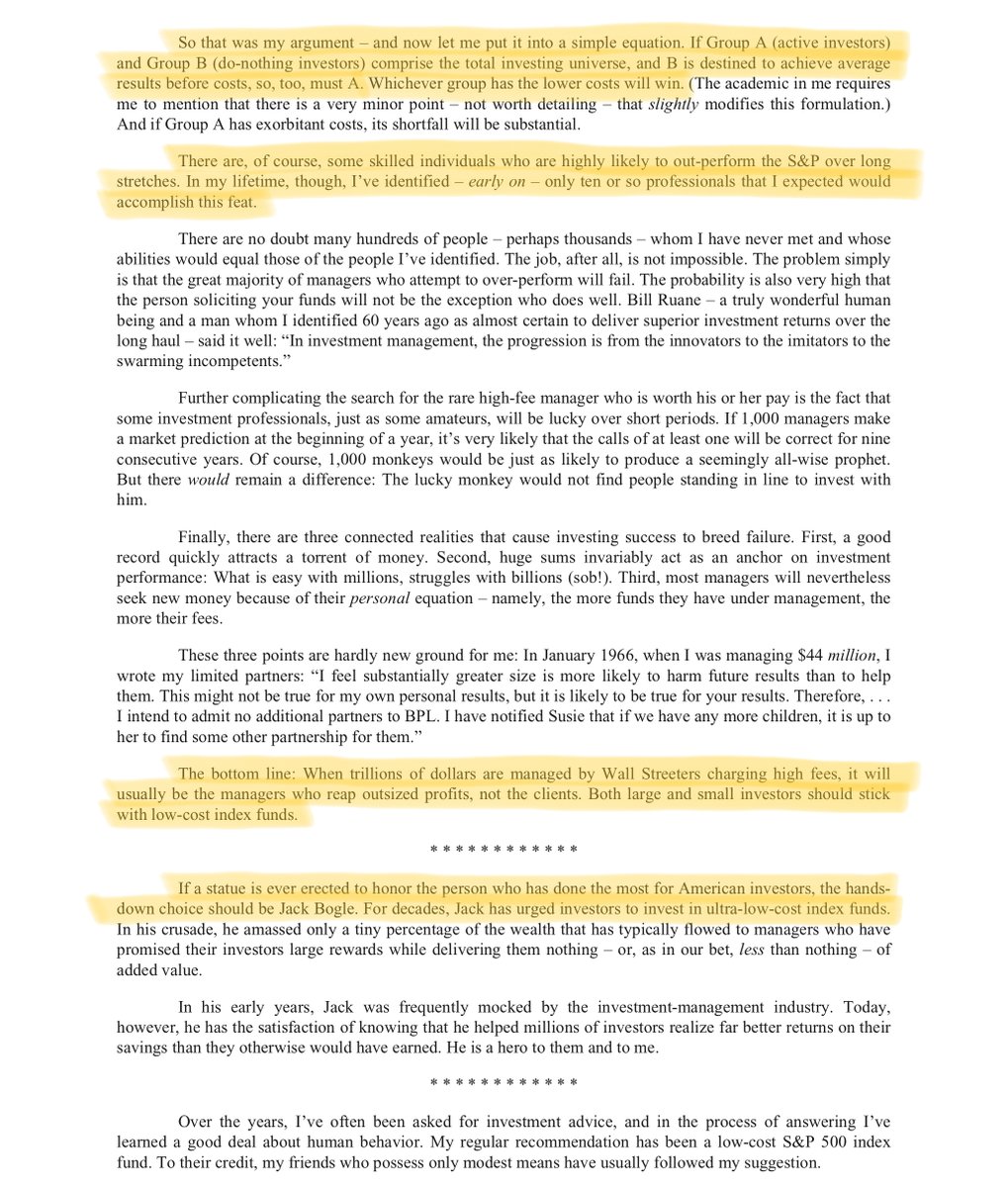

Key lesson: Many fund managers do not "earn their keep". Their stock picking skills may produce superior returns for investors *before* fees, but such alpha tends to disappear *after* fees are taken into account.

But this doesn't mean all active investing is pointless.

For example, the Medallion Fund run by Jim Simons has an atrocious sounding "5 and 44" fee. But so far, the alpha generated has more than made up for the fee charged.

h/t @dollarsanddata: ofdollarsanddata.com/medallion-fund/

Still, the Medallion Fund is an exception -- not the rule.

The "rule" is: when you see high fees, it's generally a good idea to stay away.

As with all capital allocation decisions, you have to weigh the cost (the fees) vs the benefit (likelihood/track record of alpha).

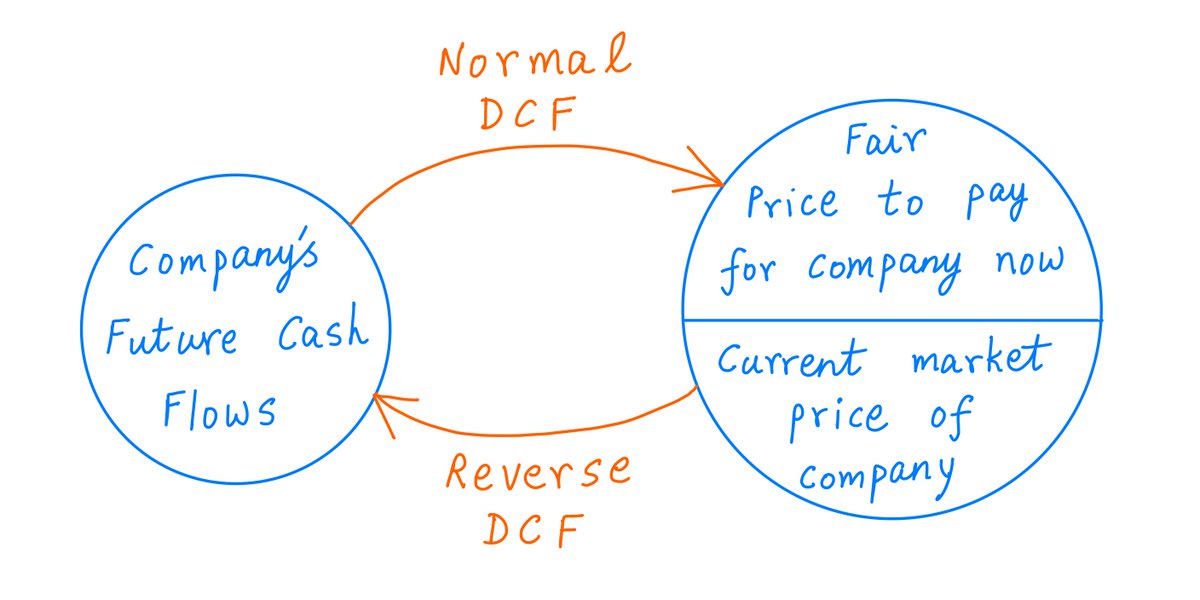

So far, our "passive vs active" comparisons were purely *financial*.

But there are also *psychological* factors to consider.

Many people find it hard to stick to a passive plan for decades. The temptation to venture off course is high, especially during bubbles and such.

If a fund manager can help you stay the course, without panicking, during periods of high volatility, bubbles, etc. -- then hiring him may be the right decision even if it produces no alpha. Because without his involvement, you would have lost a lot of money.

So, if you do decide to go "active", how do you choose a fund manager? What do you look for?

First, you must be sure of their honesty and integrity. After all, you're trusting this person with your hard earned dollars. You don't want a Bernie Madoff type situation.

Second, you should be able to freely discuss your portfolio goals, as well as your broader financial goals, with them.

As with any long term relationship, it helps to have your expectations clearly communicated.

Third, you should be comfortable with their investing philosophy and process: the kinds of economic characteristics they look for in a company, the level of rigor, depth of research, intellectual ability, common sense, and rationality they bring to their analyses, etc.

Fourth, you should understand their compensation and fee structure thoroughly.

Do they have a fiduciary responsibility to you? Are their incentives aligned with yours? How much of their personal net worth is invested alongside your money? Do they eat their own cooking?

As usual, I'll leave you with a few references.

Let's start with Buffett's 2006 letter, where he tells us what he thinks of the "2-and-20" fee structure:

berkshirehathaway.com/letters/2006lt…

I also like Fred Schwed's short book, "Where are the Customers' Yachts?" -- a reminder that Wall Street firms have always made money from fees, and that individual investors would do well to steer clear of such high-fee offerings.

amazon.com/Where-Are-Cust…

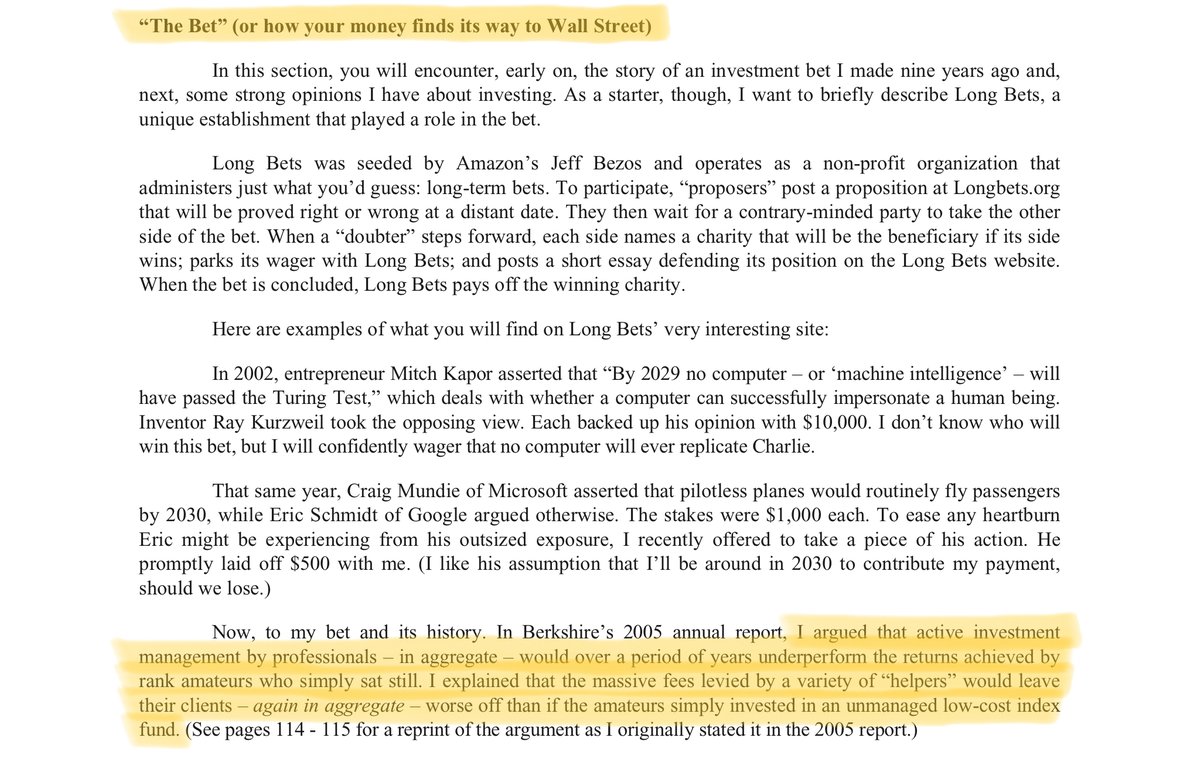

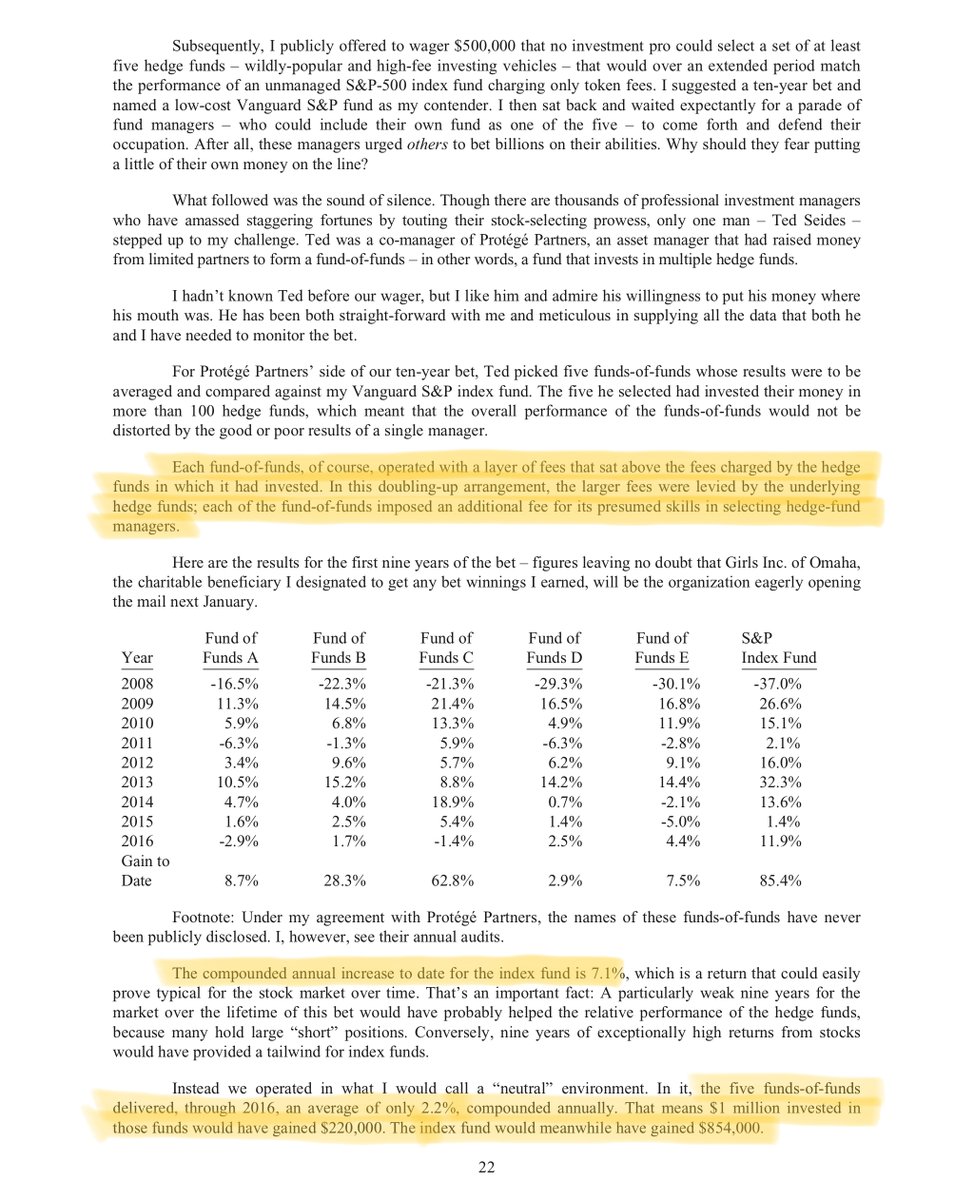

There's also Buffett's famous 10-year "passive vs active" bet against @tseides.

Note this: Buffett, the world's most famous active investor, called the bet for the *passive* option. And won the bet!

Details from his 2016 letter:

berkshirehathaway.com/letters/2016lt…

And finally, here's a video by @MohnishPabrai that discusses the zero fixed fee structure used by Buffett's own partnership in the 1960s (which Mohnish subsequently cloned).

In our terms, it's a slight variant of {F, V, H} = {0, 25, 6}.