Another key finding of the report on the EPSRC funding portfolio and gender is that the salaries requested by men are higher than those requested by women, and this gets more marked with the age of the applicant. epsrc.ukri.org/files/aboutus/…

The report is not entirely clear on this point. We *think* it is referring to the salary rates which PI’s request for their own contribution to the research project. The numbers in the report include the pension and oncosts in these salary rates.

Assuming we’re interpreting this correctly, it’s important to realise that the salaries PIs request on their grants do not reflect any kind of self-evaluation. These are the salaries set by the Institutions who employ the PIs, who are paying men more than women of a similar age.

This is reflective of what is already known about the gender paygap in Universities: According to @ucu the mean gender paygap in Universities in 2019 was a whopping 15.1%. ucu.org.uk/genderpay

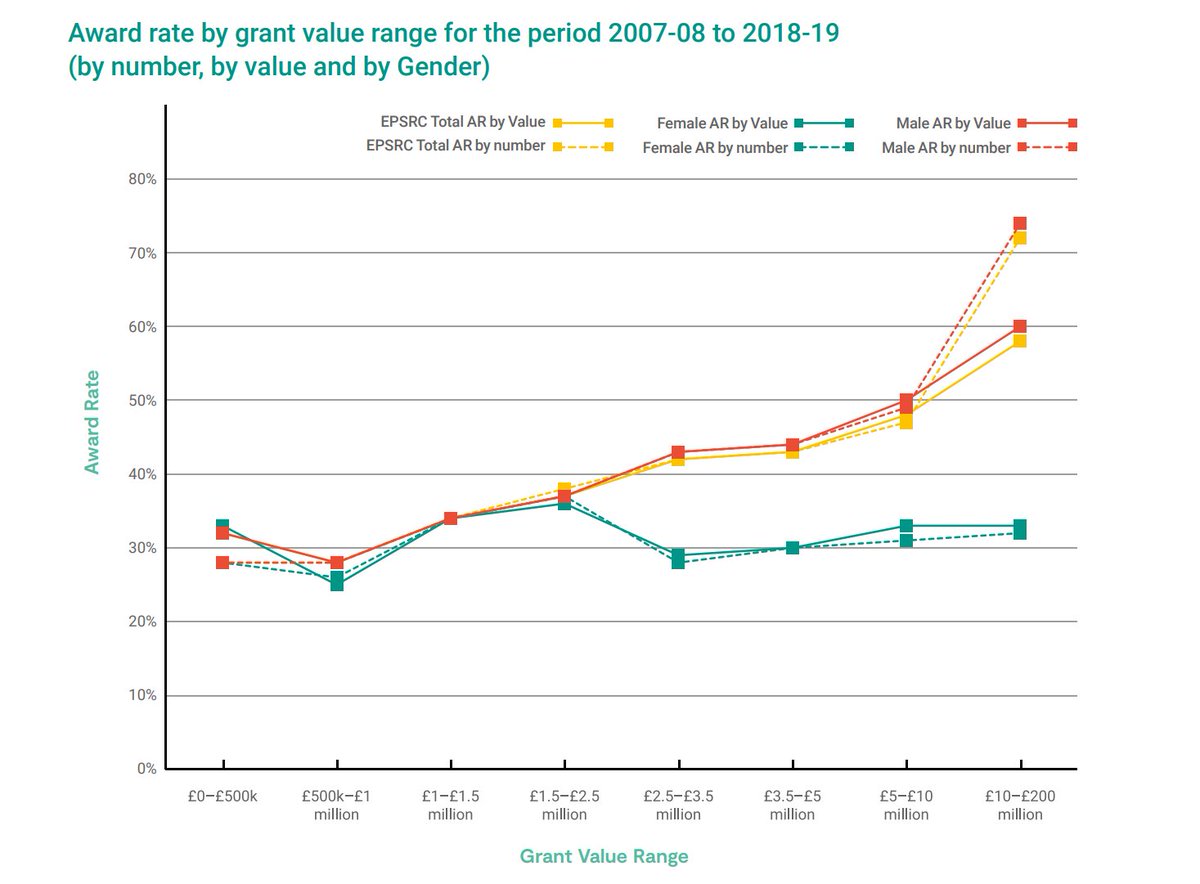

How do questions of grant funding relate to the gender paygap, particularly for senior academics? Well - being able to pull in big grants is a great way to get that promotion or pay rise, and this report shows that is more difficult for women than for men.

The data on salaries in the EPSRC report thus strikes us a symptom of the problems women face with access in grant funding - and just one aspect of the broad range of impacts that inequalities in funding have on women’s careers, opportunities and scientific work.

We’ll talk about the impact of these issues more tomorrow. In the meantime, don’t forget to let EPSRC know more about what you think of these issues, by filling in their survey:

surveymonkey.co.uk/r/KGN98VK

surveymonkey.co.uk/r/KGN98VK

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh