John Ioannidis, of "Most Published Research Findings Are False" fame, has now had his paper on IFR published

Let's do one, final, twitter peer-review on the study 1/n

Let's do one, final, twitter peer-review on the study 1/n

2/n You can find the study here

who.int/bulletin/onlin…

And my previous threads on it here

who.int/bulletin/onlin…

And my previous threads on it here

https://twitter.com/GidMK/status/1283232023402868737?s=20

https://twitter.com/GidMK/status/1262956011872280577?s=20

3/n I should say at the outset here - the only personal comment I would like to make about Professor Ioannidis is that he is a very smart man who I respect tremendously

I will, however, examine the paper, because I think that is what science is all about

I will, however, examine the paper, because I think that is what science is all about

4/n At first glance, and indeed on deeper reading, it is clear that very little has changed from my previous looks into the paper

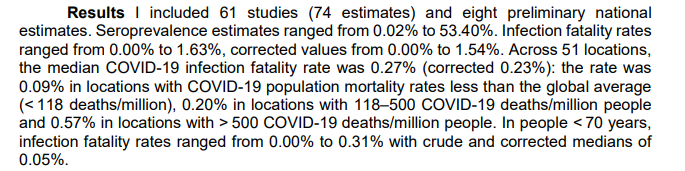

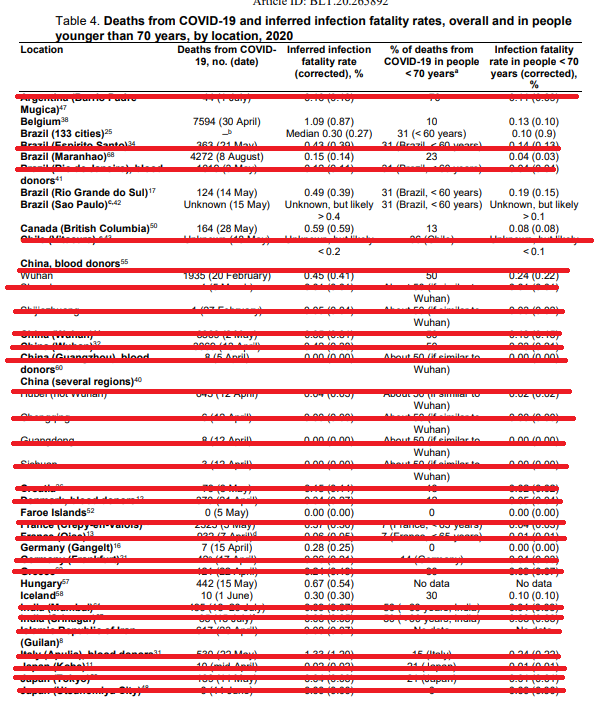

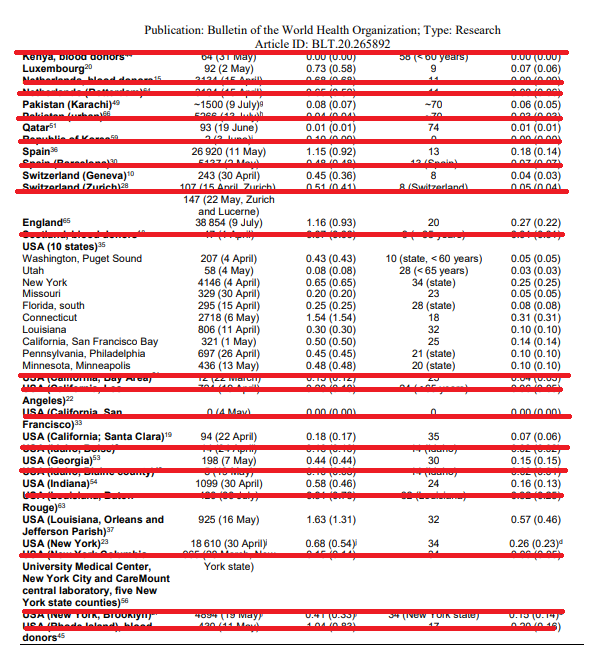

5/n The methodology is still the same, and the eventual conclusion remains that the median IFR of COVID-19 is 0.27% (originally he estimated 0.26%)

6/n The author then concludes that the IFR "tended to be much lower than estimates made earlier in the pandemic", which is odd because his own estimates made earlier in the pandemic (in May) were...lower

7/n Indeed, as we can easily see, the resulting low IFR is simply a consequence of the low quality of the review itself and has very little to do with when the estimates were made

8/n For example, the review does not adhere to PRISMA guidelines (the most basic recommendations for reviews of this kind) which is very strange given that Prof Ioannidis himself is a co-author on the original PRISMA statement

9/n This has lead to a problematic situation, where there is no rating for study quality, publication bias, and indeed little consideration in the manuscript for how the quality of the published evidence might impact the review

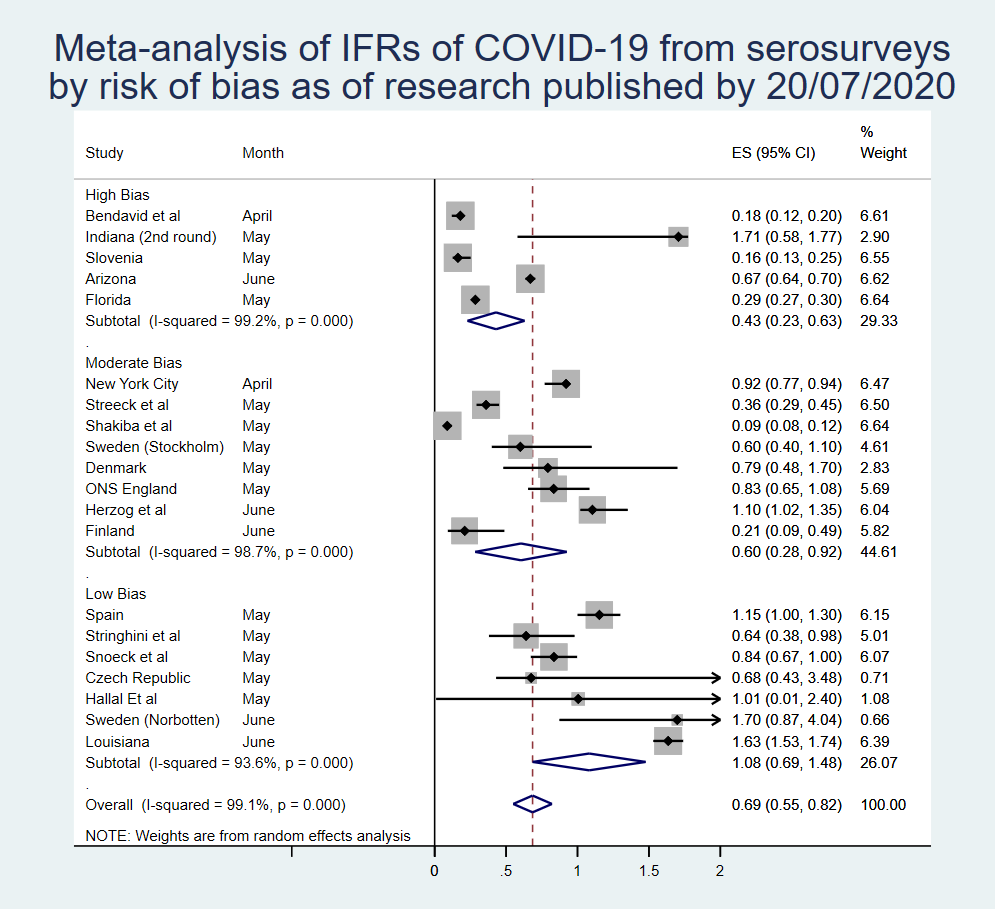

10/n As we pointed out in our systematic review and meta-analysis of COVID-19 IFR, this is an issue because higher-quality studies tend to show a lower seroprevalence and thus a higher IFR

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

11/n (Interestingly, Ioannidis cites our study but gets the numbers wrong, in what is distressingly something of a trend in the paper generally - we actually estimated 0.68% in the published paper which came out recently)

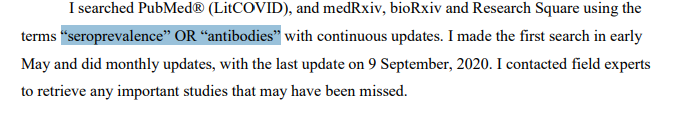

12/n We can see the issue with non-adherence to PRISMA in the methods section. These are clearly not the search terms used, as entering them into these databases results in 100,000s of results

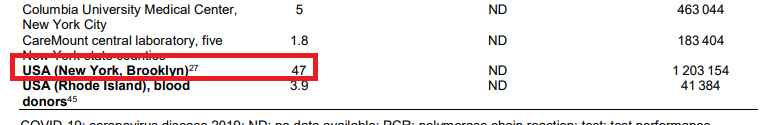

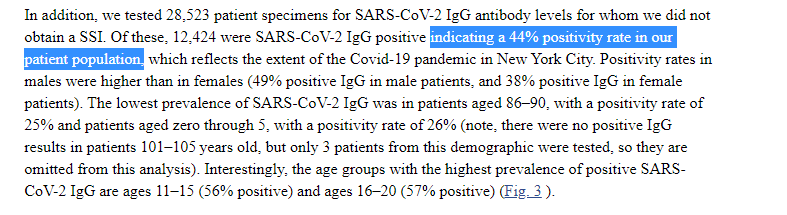

13/n There are also still clear numeric errors remaining from previous versions of the study. For example, this number from a paper looking at people going to hospital in New York should read 44%, and not 47%

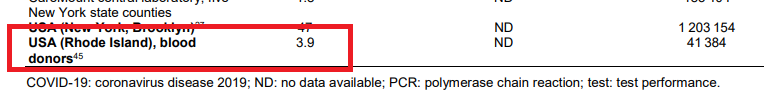

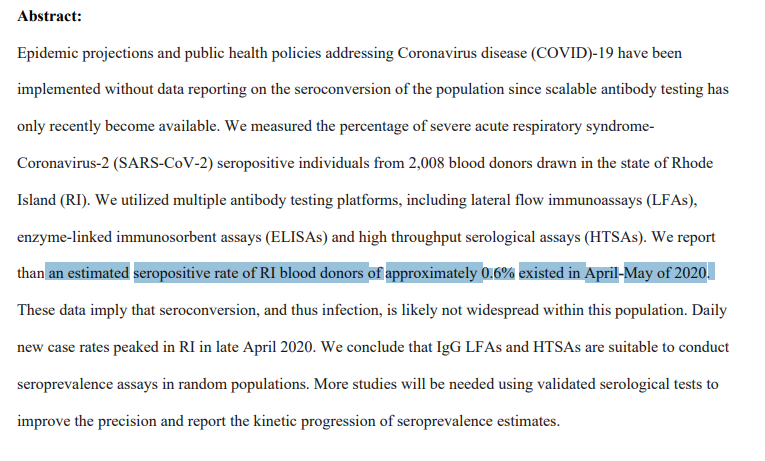

14/n And there are new errors as well. In this study of blood donors in Rhode Island, the authors estimate a seropositivity of 0.6%, while the review paper has 3.9% instead

15/n But by far and away, the biggest error in the text is simply to do with using clearly inappropriate samples to estimate population prevalence

This is a fundamental flaw in the paper, and really something of a basic epidemiological mistake

This is a fundamental flaw in the paper, and really something of a basic epidemiological mistake

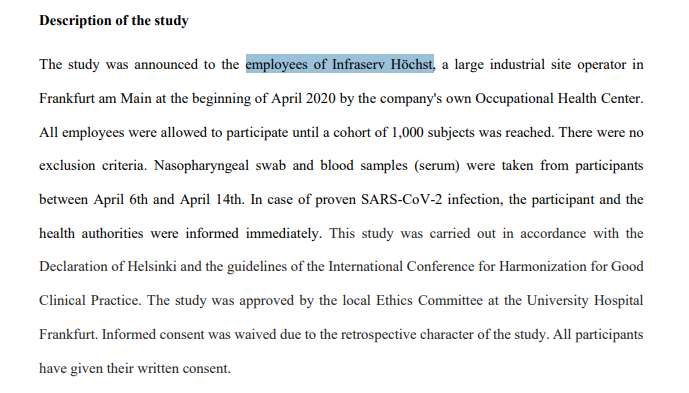

16/n Some of these studies are just so clearly inappropriate to infer a population estimate that it doesn't really require explaining. Samples of a single business in a city, or inpatient dialysis units

18/n Then we have blood donors, who again may give an erroneous result. These are people who, DURING A PANDEMIC are happy to go out and about and give blood. It is quite possible that they are MORE likely to have been infected than the general population!

18.5/n There are also a lot of included studies from places in which there is almost certainly an enormous undercount of deaths

For example, India, where the official death counts may represent a substantial underestimate bmj.com/content/370/bm…

For example, India, where the official death counts may represent a substantial underestimate bmj.com/content/370/bm…

19/n A very basic, reasonable thing to do would be to conduct a sensitivity analysis excluding these biased estimates, to see what happens when you only use representative population estimates

Which we can do

Which we can do

20/n If we take the median of only these somewhat good-quality studies (some of them still aren't great, but at least they're not clearly inappropriate), we get a value of 0.5%

Double the estimate of 0.27%

Double the estimate of 0.27%

21/n I thought at this point I'd briefly look at blood donor studies, because they are an interesting case study

The author argues that these should be included because, due to "healthy volunteer bias", at worse any estimate should bias the IFR results upwards

The author argues that these should be included because, due to "healthy volunteer bias", at worse any estimate should bias the IFR results upwards

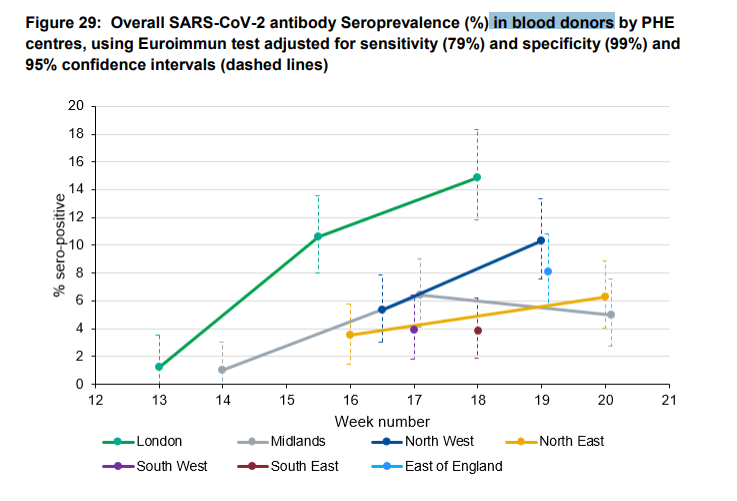

22/n Well, we can now actually test this theory and see if it is true. Enough studies have been done that we have COVID-19 seroprevalence estimates from BOTH blood donor studies AND representative samples and compare them

23/n For example, in England an ongoing study on blood donors by PHE estimates that 8.5% of the population has developed antibodies to COVID-19

However, the ONS with their massive randomized study puts the figure at 6% instead

However, the ONS with their massive randomized study puts the figure at 6% instead

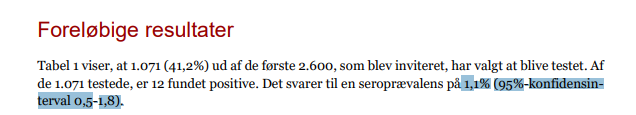

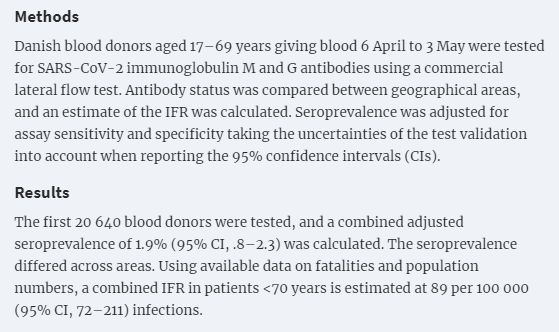

24/n In Denmark, a robust population estimate put the figure at 1.1%, while their blood donor study estimates 1.9% have been infected previously

25/n Indeed, in every location where both a non-probabilistic, convenience sample has been taken (not just blood donors) AS WELL AS a well-done population estimate, the convenience sample overestimates the seroprevalence

26/n We have a new paper that we're working on that suggests that using such estimates will usually overstate the true seroprevalence by a factor of about 2x

Which means the true IFR would be double the number computed from such studies

Which means the true IFR would be double the number computed from such studies

27/n There are also still, after many revisions, studies that have been excluded inappropriately from the estimates

This study from Italy, for example, which produces an estimate of 7% (!) for IFR in the region

This study from Italy, for example, which produces an estimate of 7% (!) for IFR in the region

29/n Similarly, there are numerous country-wide efforts not looked at in any way, such as the large population studies conducted in Italy (150,000 participants) and Portugal (2,300 participants)

30/n And while there is a very brief discussion of the variation in IFR by region, the main component (age) - as we have demonstrated - was barely addressed, with the author instead focusing on vague speculation about healthcare systems medrxiv.org/content/10.110…

31/n We can actually see how age of those infected impacts IFR quite neatly from some of the studies in this review

Qatar (0.01%) and Spain (1.15%) look very different, right?

Qatar (0.01%) and Spain (1.15%) look very different, right?

32/n Wrong! In fact, the difference here is entirely explained by age!

In Qatar, infections have mostly been limited to the immigrant worker population (<40 years), with this group representing more than 50% of infections

In Qatar, infections have mostly been limited to the immigrant worker population (<40 years), with this group representing more than 50% of infections

https://twitter.com/GidMK/status/1300938689535565824?s=20

33/n Since this group is at a very low risk of death from COVID-19, the population IFR is MUCH lower than in Spain, where infections among the elderly have been much more common

34/n All of these errors are a shame, because to a certain extent I agree with the author

IFR is NOT a fixed category. In the metaregression linked above in the thread, we demonstrated that ~90% of variation in IFR between regions was probably due to the age of those infected!

IFR is NOT a fixed category. In the metaregression linked above in the thread, we demonstrated that ~90% of variation in IFR between regions was probably due to the age of those infected!

35/n Unfortunately, Prof Ioannidis appears not to have read this study, but if you are interested here is the preprint version to peruse medrxiv.org/content/10.110…

36/n Anyway, there are numerous errors remaining in the text that I haven't pointed out, but if you've reached this far in the thread I'm sure you're tired of me telling them to you straight up. Have a really careful look and see if you can find them!

37/n (As a start, there is now a representative population estimate from Wuhan out that implies an IFR SUBSTANTIALLY lower than the ones inferred in this paper from samples including hospitalized patients)

38/n Regardless, the main take-home remains, unfortunately, that this paper is overtly wrong in a number of ways, it does not adhere to even the most basic guidelines for this type of research, and thus the point estimate is probably wrong

39/n Sorry, typo in tweet 37 - should read an IFR SUBSTANTIALLY *higher*, not lower. The SEROPREVALENCE is lower (at ~2%) which implies an IFR of ~1.2%

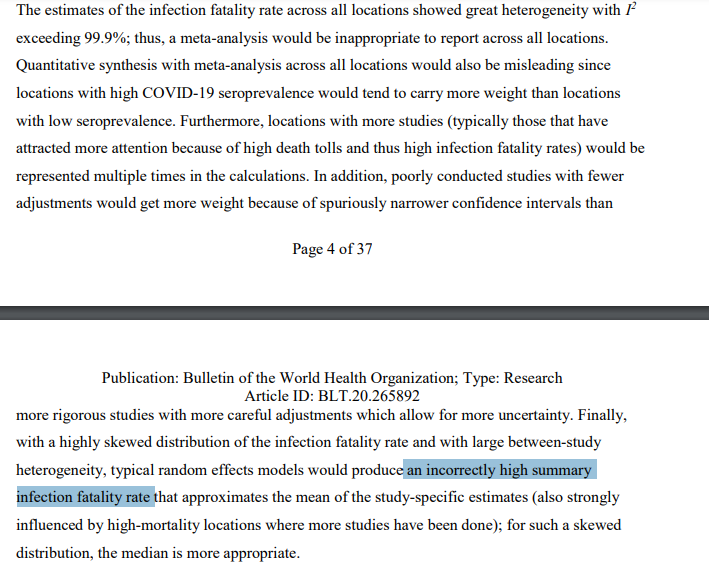

40/n Oh, on an unrelated sidenote, it's quite funny that the author spends some time arguing that using a median is more appropriate than doing a R-E meta-analysis (as @LeaMerone and I did), so I quickly calculated the median for our study and it is higher at 0.79% for IFR 😂

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh