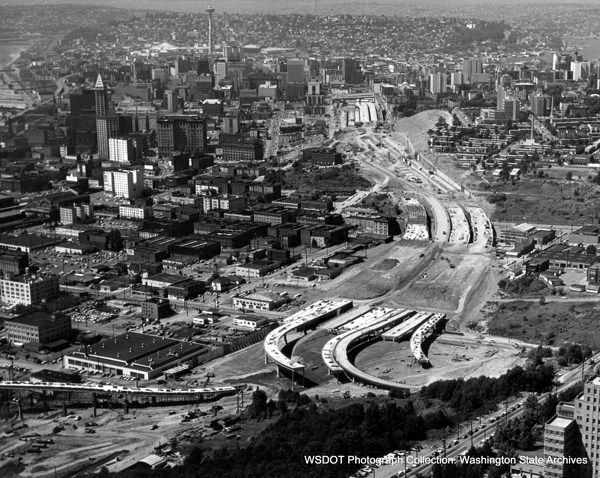

1/ What's in common between the two major urban interventions pictured below, a NA urban freeway and an Italian boulevard? Nothing apparently

Well, not really. Both interventions originated from the same logic of accessibility and resulted in the displacement of poor people

Well, not really. Both interventions originated from the same logic of accessibility and resulted in the displacement of poor people

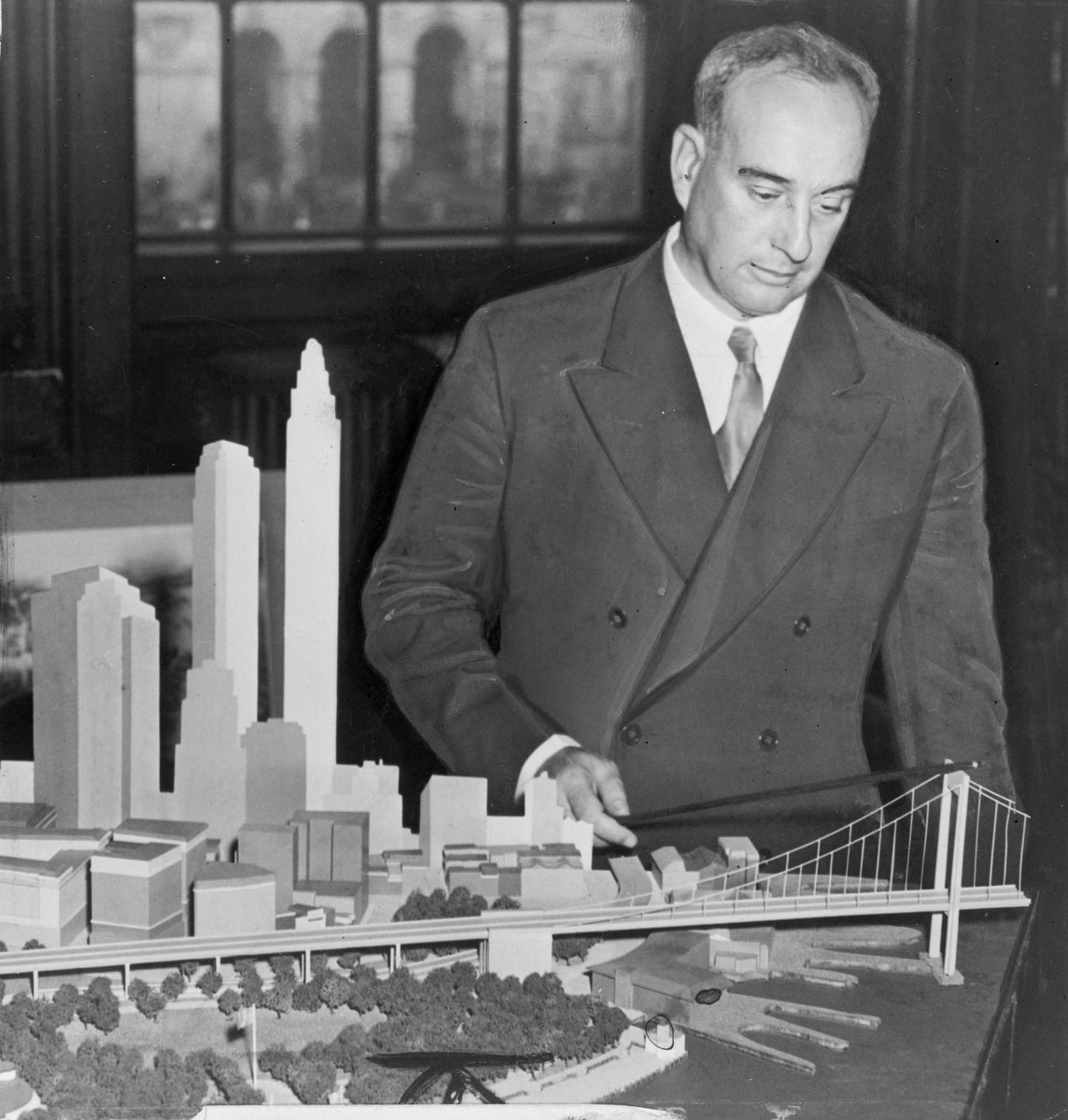

2/ You all know very well the story of US inner-city freeways, the way they were cut through poor, often minority's neighborhoods to increase accessibility of CBDs from the growing white collar suburban sprawl. No need to remind the logic and the results.

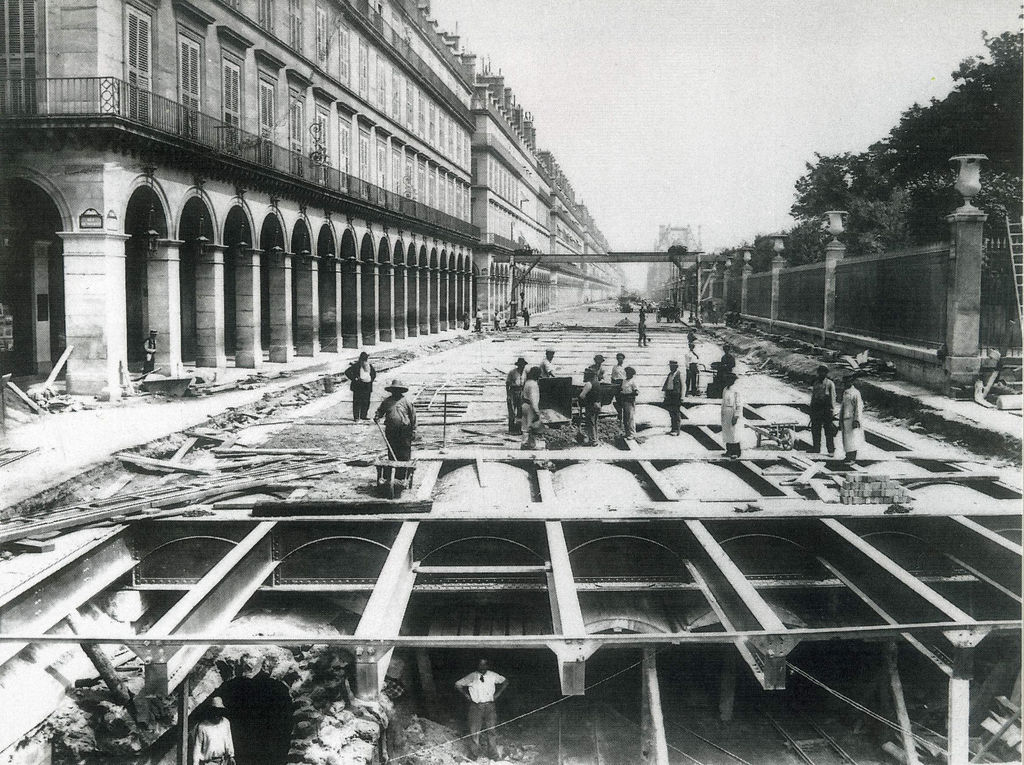

3/ Maybe lesser known is the opening of new thoroughfares in existing urban fabric that characterize part of the European urban planning in the second half of the 19th century. Of course, everybody knows Haussmann's Paris

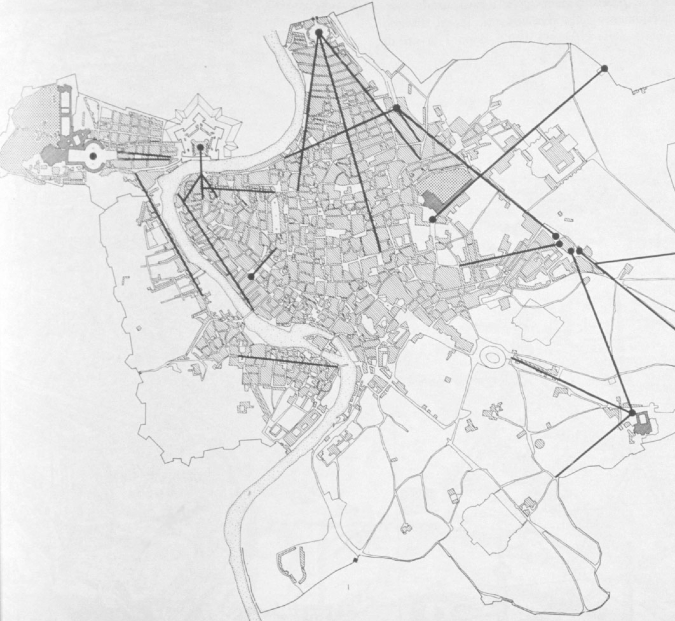

4/Well, without being so systematic or grandiose,a similar approach was applied in southern European cities too (and the colonies, but that's another story).It's not just a copy of Hausmann's approach, is more the natural evolution of a long tradition starting with papal urbanism

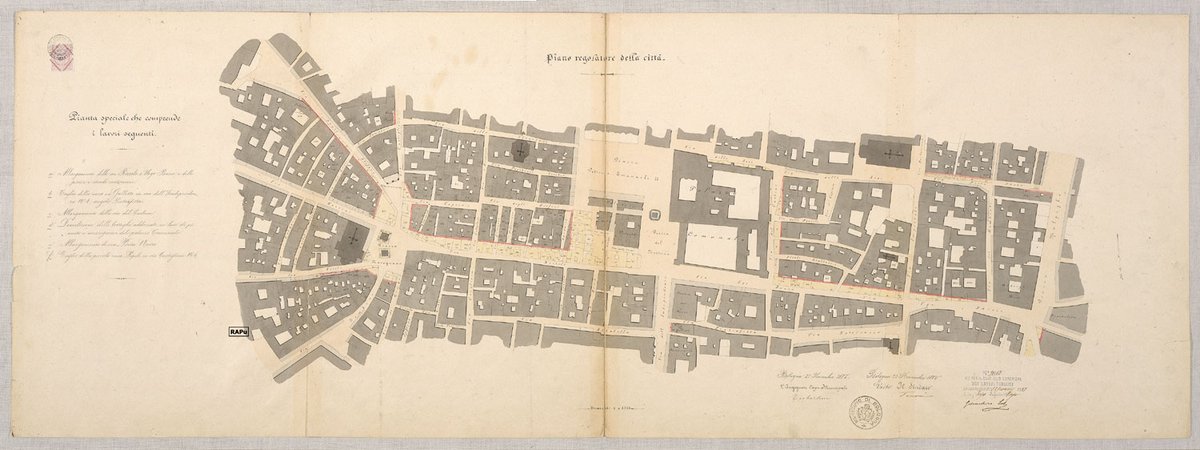

5/ The first planning law in Italy, the 1865 expropriation law, gives municipalities the possibility to draw a "regulatory plan" (piano regolatore), that entrusted them with the power to expropriate land and buildings to open up new thoroughfares

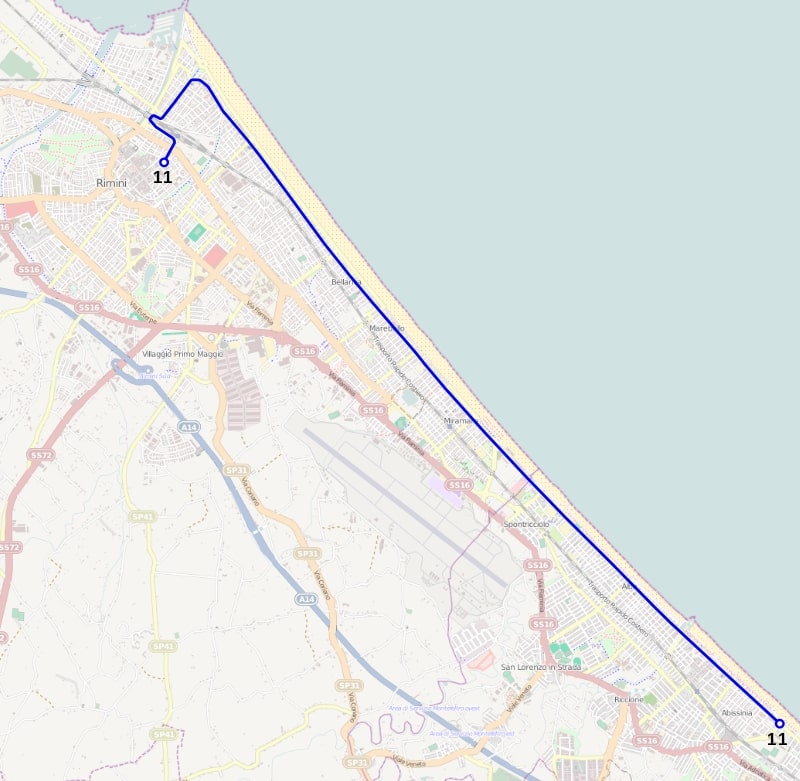

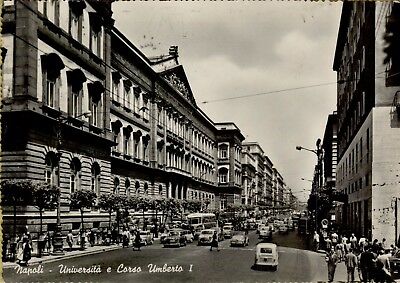

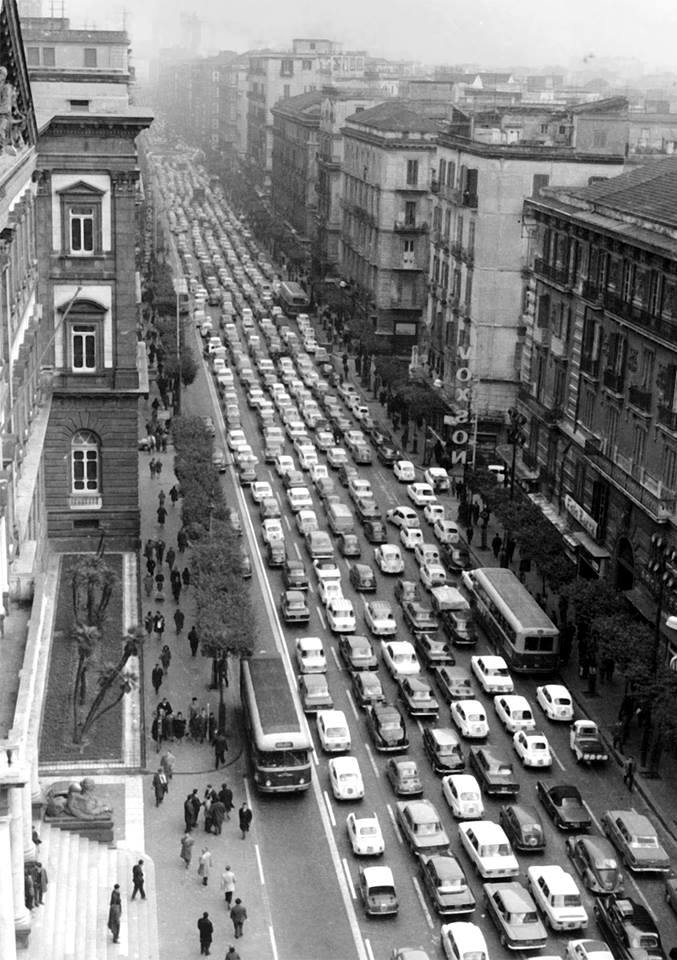

6/ This resulted in several wider or more chirurgical demolitions within the old city, typically to open up boulevards to connect the city center with the railway station. via Indipendenza in Bologna and the "Rettifilo" in Naples are typical examples.

7/ Both the justification and the background were similar. On one side, increase accessibility to the Old city core, that was transforming in a sort of CBD with directive functions. In the era of the automobile, the result was not much different than a NA urban motorway

8/ On the other side, clean up and "sanitize" (risanare) poorer neighborhoods. Not surprisingly, Naples plan arrived after a devastating cholera outbreak and the parliamentary debate on the special law of 1885 was characterized by a moralistic stigmatization of the urban poor

9/ Does this ring a bell?

That said, the formal outcomes were indeed different, as those major urban restructurings were carried out in different eras, before and after the advent of mass motorization. But the background is similar, in a way

That said, the formal outcomes were indeed different, as those major urban restructurings were carried out in different eras, before and after the advent of mass motorization. But the background is similar, in a way

10/ It would be interesting to imagine an alternative scenario where US central areas were "Haussmannized" instead of "Robert-Mosesized". The physical conditions were there: although, apart maybe Boston and Québec, no NA city had a real medieval core, roads were not so large.

11/ Take Montréal, for example: no major N-S street is larger than 25m, most being 20 or less. E-W is even worse, and that for the whole city expansion until the 1940s, in an area much larger than central Paris. Paris boulevards range from 35m to the 70m of the Champs-Élysées

12/ There are not only bad car-related reasons for a grid of larger roads. It's where tramways with reserved ROW were built. It's what made possible to build Paris's extensive métro mostly in C&C. This is what allows some Asian cities to build mostly elevated metros

13/ Maybe NA had just an unlucky timing, as it decided it was able to perform grand urban schemes in the wrong historical moment, where the car looked like the queen of mobility, mass motorization happened much earlier than in Europe and there were to much money

14/ Of course, you may argue that these are two incomparable urban transformations. The physical outcome is. But do not forget that the displacement is not an exclusive of american freeway construction but the inevitable outcome of large urban transformations we just forgot.

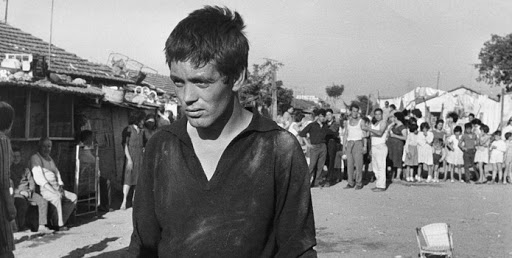

15/ The "Borgate", the precarious shantytowns in the outskirts of Rome that Pier Paolo Pasolini described so well in his movies, like the memorable "Accattone", are also the result of the massive displacement of poor people caused by Mussolini's 1930s urban renewal schemes

16/ The two sides of the pond, sometimes, are more similar than one might expect.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh