1/ After a recent exchange, here is a thread about the interconnectedness of global and local urban geographies of production and jobs and how they shapes mobility and planning with two Italian examples you never probably heard about : Mirandola and Porretta Terme

2/ The first example is Mirandola, a town of some 20k inhabitants is the flat lands, some 30km North of Modena. You'd probably know it better for being within the production area of both Parmigiano and the Balsamic Vinegar of Modena. But that somehow secondary.

3/The most important thing is that Mirandola is the main center of a cluster of biomedical manufacturing, accounting for more than 1 Bn of annual output, 70% exported, making it the world third largest after Minneapolis and Los Angeles. And that is a city of 20k that looks like⤵️

4/ It's a typical example of manufacturing clusters (distretti industriali), where small and medium size entreprises are horizontally integrated, management is almost informally organized, and labor relationships are less mediated than in large corporations.

5/ This system is rooted in a long collaborative tradition (the corte bracciantile) and many enterprise owners are former workers of molding industries that just went independent in the 1970s, starting a business in a then expanding sector where they can use their molders skills.

6/ When the 2012 earthquake hit this area, the media concentrated mostly on the potential disruption in the food industry, with raising Parmigiano's prices. But the real problem was a short term shortage of biomedical equipment, as factory collapse disrupted global chains

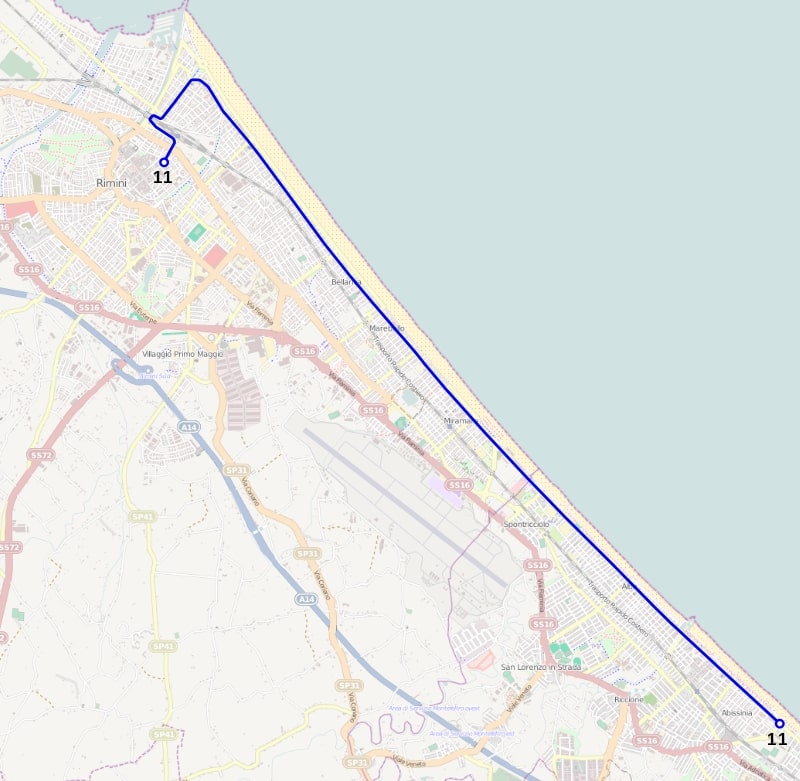

7/ The other example si Porretta Terme, an even smaller town (some 5k) nested in the middle of the Apennines. Well, how can a similar place be "global"? It has all the characteristic of a marginal territory. Well, yes and no

8/ In the outskirts of the city there is the HQ of Pi-Quadro, a leather accessories producer you probably heard about. The story is one of a subcontractor of fashion industries located in an anonymous warehouse in the valley that decided to go independent.

9/ It started in its old location to design its own product. Now they have a new shiny headquarter far from any big global city, from which they design and organize a production chain where leather is produces in Tuscany, assembled in China and sold worldwide

10/ Just-in-time shipping for very high value-to-weight products, like wallets and bags, means that the HQ- logistic center can easily locate in a relatively remote area, since the last 40km from Bologna are nothing in the the long Tuscany-China-Italy-World product chain.

11/ When I visited them back in 2008, they said that the choice of the location was based on proximity to the old site and to the main producers of their leather, Tuscanian tanners, but also to the ease of access to planning authorities

12/ It was much easier to find the right place and to expedite the bureaucratic procedures for the new HQ in Porretta, where the city planner even accompanied them around to evaluate the potential sites, than in a large city like Bologna, where you are just a dossier among others

13/ The consequences for planning are mixed: on one side, this diffused manufacturing sector made for a more geographically distributed wealth in Emilia Romagna, notoriously a region with less centre-periphery dichotomy and a more egalitarian distribution of wealth

14/ On the other side, the dispersed nature of job makes for a much more complicate environment for mass transit. Transit mode share has constantly declined in Emilia-Romagna in the last 3 decades and blue collars account for a very small percentage of transit users

15/ The situation is even worse in Veneto, a region with similar economic patterns but different urban policies, that didn't prevent complete geographic dispersion but, on the contrary, reinforced them.

16/ Those development patterns have consequences for that. Places like Mirandola, low density but compact and with a clear city center, have quite high (in the 10s%) levels of bike commuting despite having little dedicated infrastructures. Bike more than transit is the answer

17/Of course logistic and other mobility needs would call for different solutions. But concentration/density are not the answer for everything when we talk about mobility, as we cannot force job concentration by fiat but we must deal with trends that are out of planners' control

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh