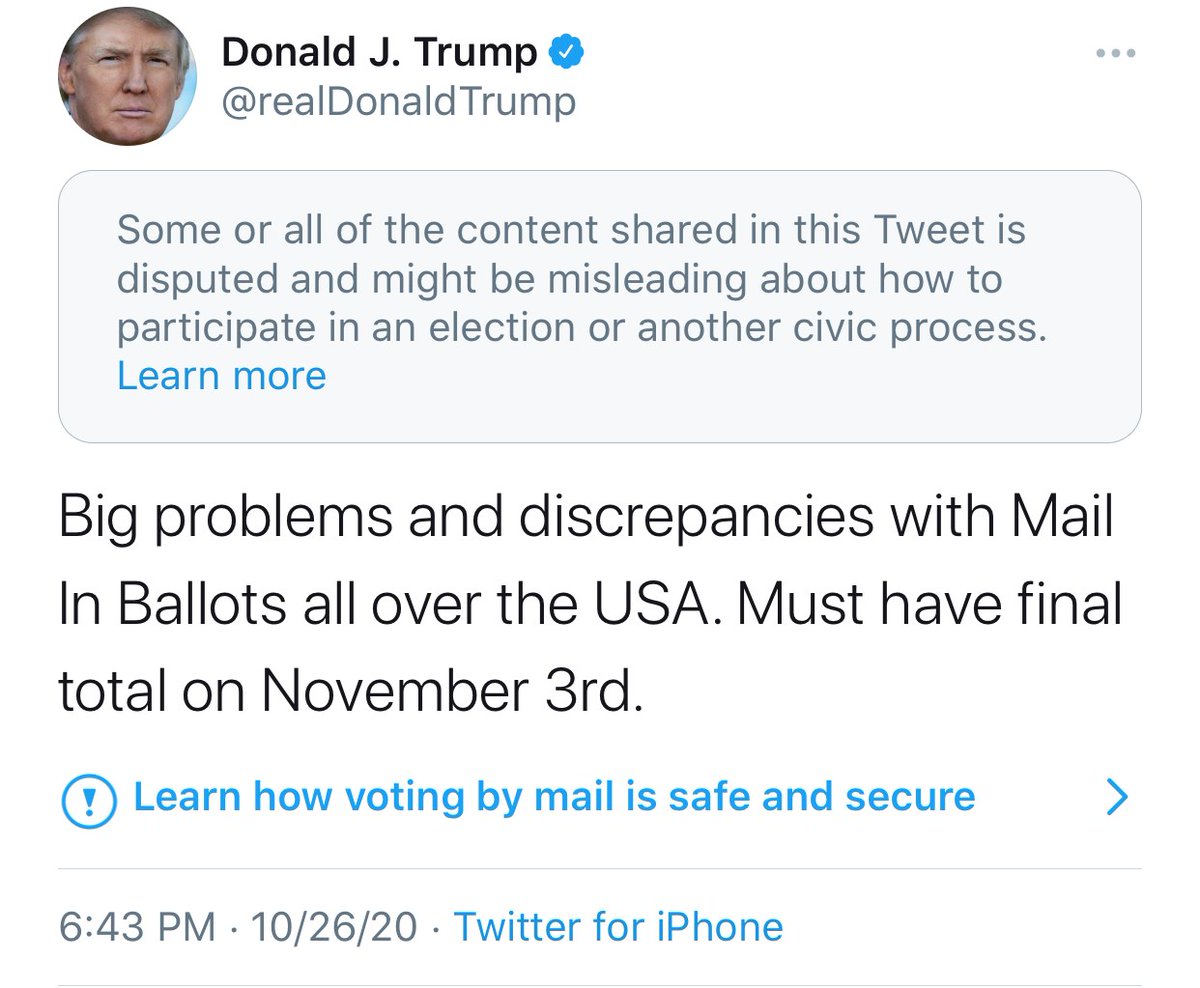

1. In response to the President's claim that we "must have final total" election results *on* Election Day, here's a #thread on how and why presidential elections *actually* work under state and federal law — and why, in fact, we've *never* had final results *on* Election Day.

2. Let's start at the beginning. A U.S. presidential election is actually 51 *different* elections (50 states + DC), in which each jurisdiction votes for presidential *electors.* It's the *electors* who vote for President — and they don't meet until *41 days* after the election:

3. Why 41 days? To give states time to finish counting. Although Election Day is fixed by law, Congress has allowed states to set their own rules about when they count ballots — including whether and to what extent to allow mail-in ballots, and by when those ballots must arrive.

4. And even for in-person ballots, it's usually not possible for states to *finish* counting *on* Election Day, especially since many state's laws don't allow *any* counting of ballots until all of the polls have closed (which happens sometime on the evening of Election Day).

5. Plus, if it's *really* close, states generally provide for automatic (and, in some cases, requested) *recounts* (like Florida in 2000), which have to take place before final results can be certified.

That's why *no* state requires certification of results *on* Election Day.

That's why *no* state requires certification of results *on* Election Day.

6. Indeed, only *one* state (Delaware, of course) has a certification deadline that's less than one week after Election Day.

Every other state waits at least a week — and some *require* waiting far longer — to officially certify their election results.

ballotpedia.org/Election_resul…

Every other state waits at least a week — and some *require* waiting far longer — to officially certify their election results.

ballotpedia.org/Election_resul…

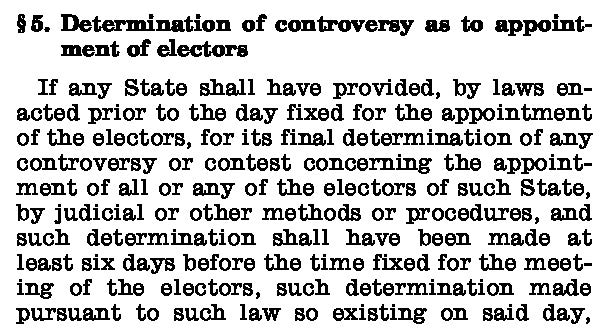

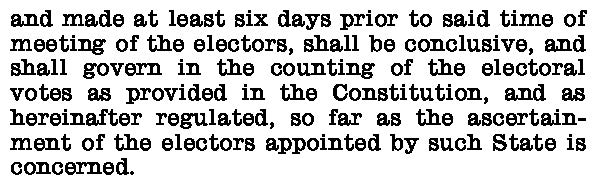

7. Federal law not only recognizes this variation; it *encourages* it.

Under the "safe harbor" provision of the Electoral Count Act of 1887, a state's results will be deemed conclusive so long as they are certified within *five weeks* of Election Day:

law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/3/5

Under the "safe harbor" provision of the Electoral Count Act of 1887, a state's results will be deemed conclusive so long as they are certified within *five weeks* of Election Day:

law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/3/5

8. On election night, what we hear are *projections* that the media makes based upon evolving vote tallies and exit polls.

And when those projections give one candidate a majority in the Electoral College, those media groups "call" the election. But *NONE* of that is "official."

And when those projections give one candidate a majority in the Electoral College, those media groups "call" the election. But *NONE* of that is "official."

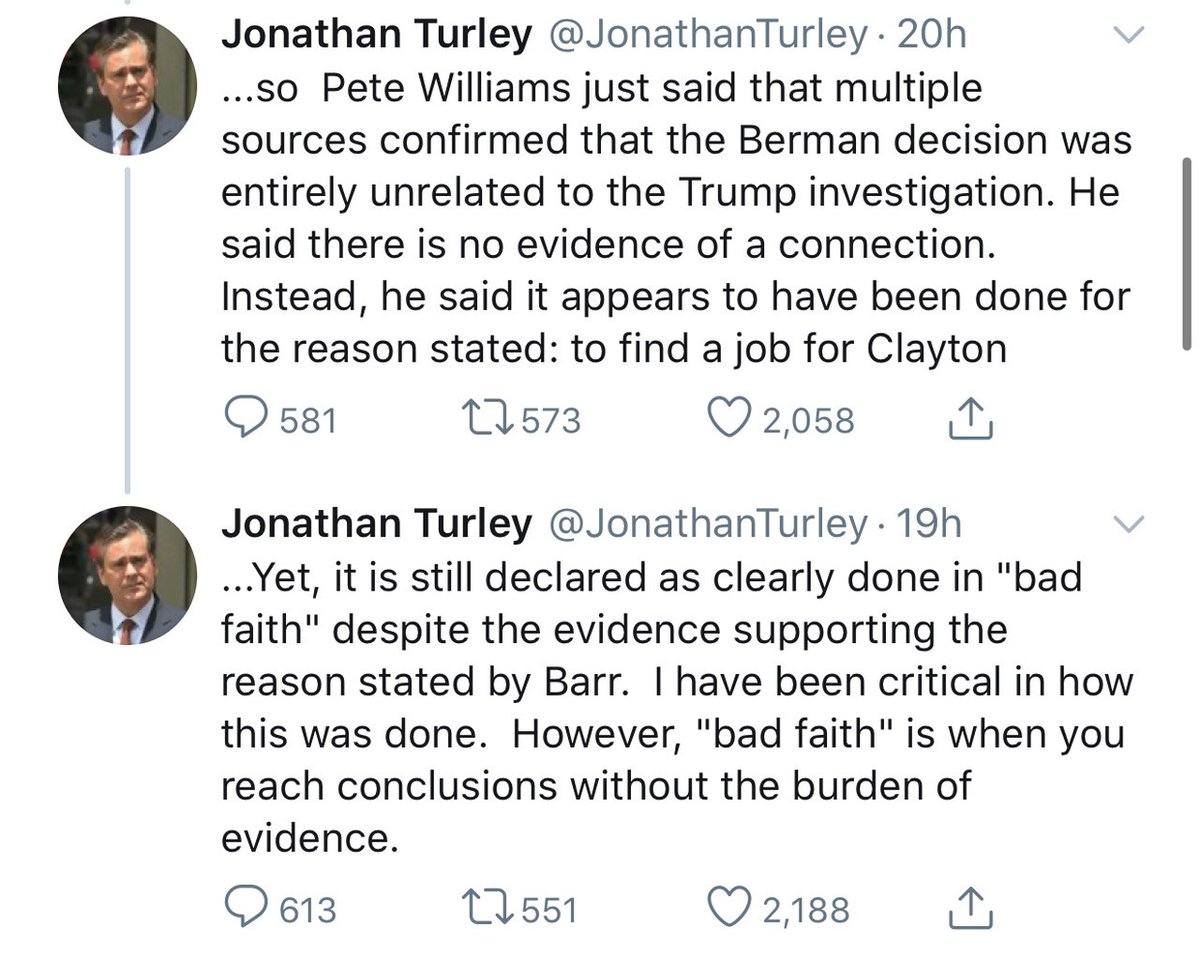

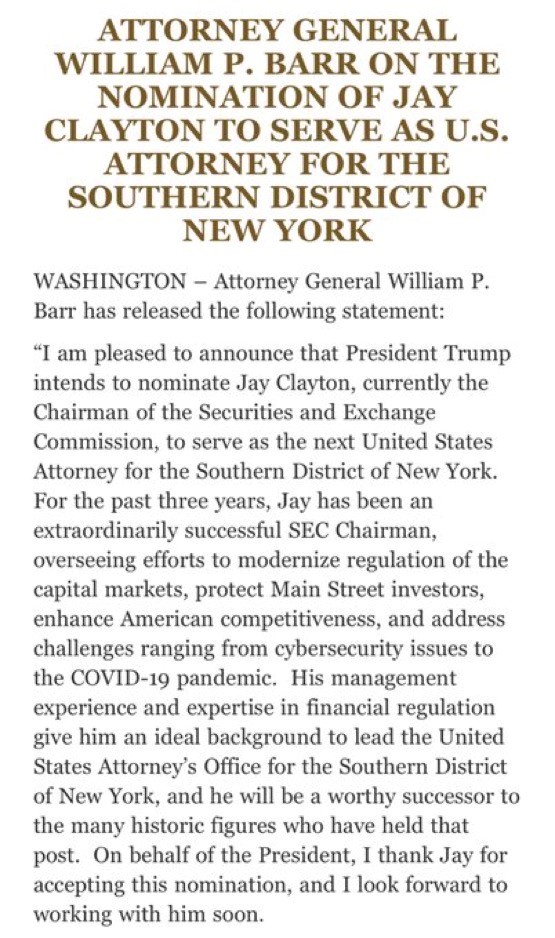

9. So when President Trump says we "must have final total" on November 3, he's just lying, both as a matter of historical practice and state and federal law. *Hopefully,* the results are clear enough by bedtime next Tuesday that the election is called for a particular candidate.

10. But if the media isn't able to call it Tuesday, that's not because of some nefarious plot; it's simply because the results are sufficiently close in the right number of states that it isn't yet clear who won — and won't be until those states finish counting all legal ballots.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh