Exciting news! @MichaelAklin and my new provocation is out in @GepJournal. We make a simple but far-reaching claim. **Empirically, climate politics is NOT primarily about collective action or free-riding**. A quick 🧵on why we've all been prisoners of the wrong dilemma 1/

For decades now, we've all assumed that free-riding is the binding constraint on global climate politics. Google "climate change" and "free-riding", and it generates 18000+ unique hits. Economists mince few words about this. Here's a Nordhaus quote for flavor: 2/

The logic of free-riding seems powerful. No country can solve climate change alone. But acting is costly. So every country wants to free-ride off of other country's action. But then no-one has an incentive to act. 3/

It's a fabulous idea. And you literally cannot overstate its influence. We've structured decades of climate negotiations on the assumption it is true. But is it? Do the empirics match this reality we've constructed? The surprising answer: not really! 4/

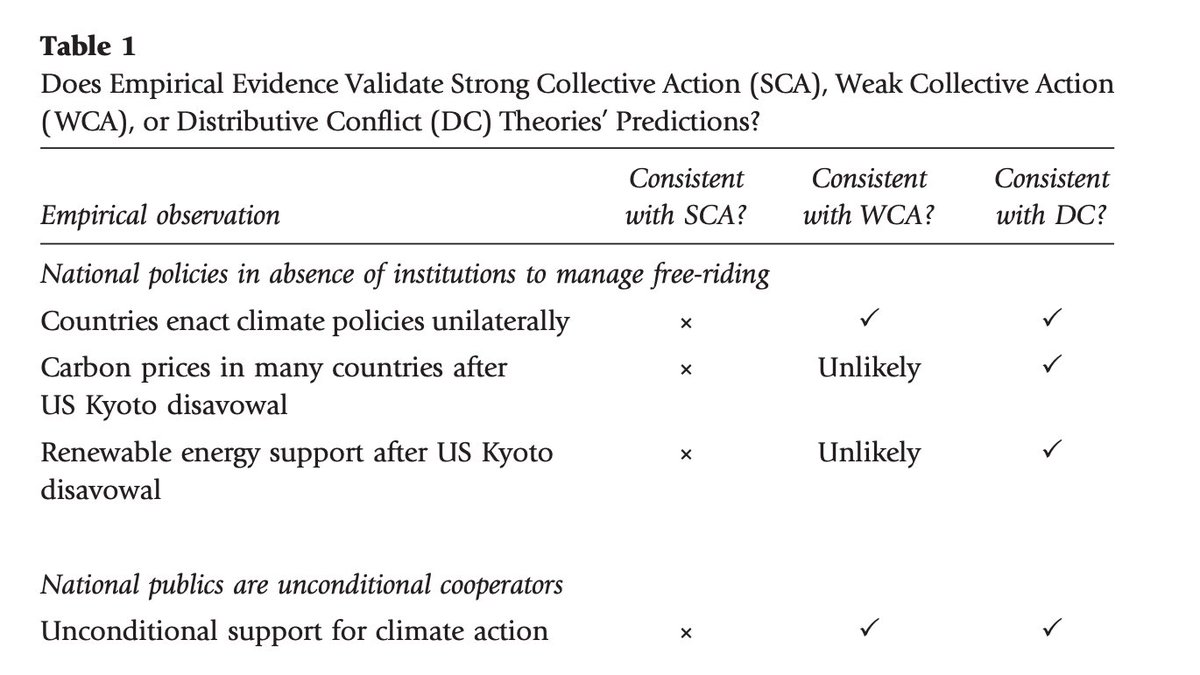

In our article, @MichaelAklin and I review the empirical evidence to evaluate whether it's consistent with our dominant collective-action flavored theory of climate politics. Shocking fact: we can't find ANY empirical evidence that shows it to be clearly correct. 5/

Instead, our review points to three things:

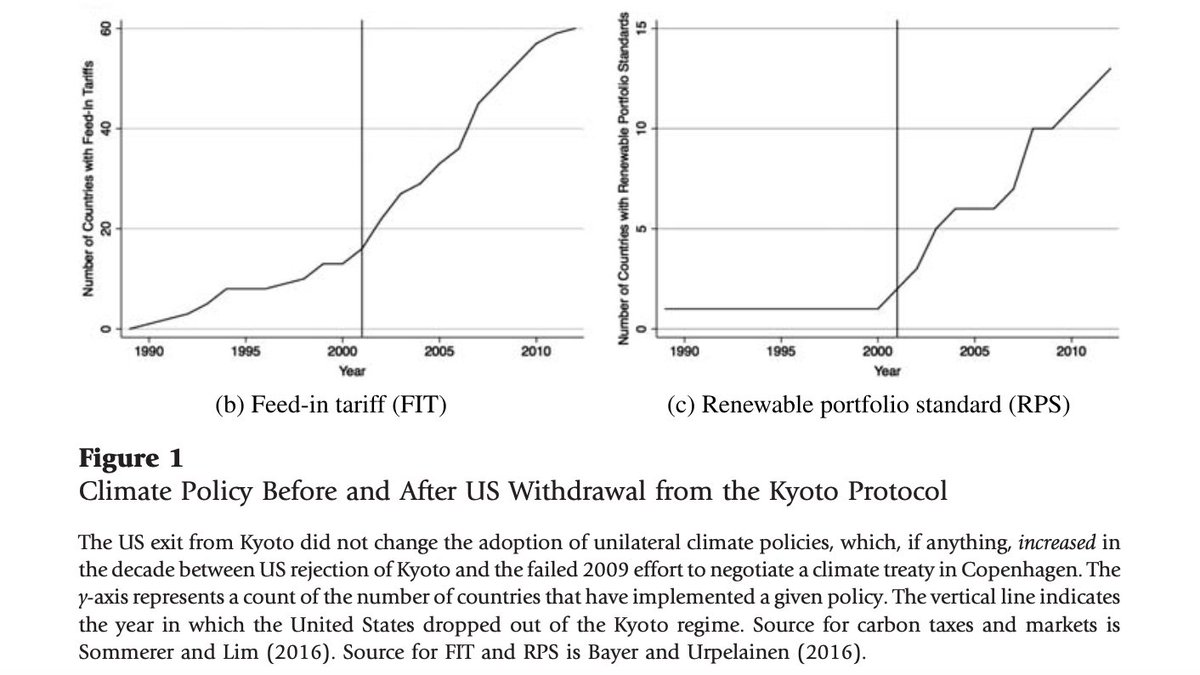

1⃣National policy action occurs in the absence of institutions to manage free-riding. For example, US leaving Kyoto did not alter pace of reforms in other countries. 6/

1⃣National policy action occurs in the absence of institutions to manage free-riding. For example, US leaving Kyoto did not alter pace of reforms in other countries. 6/

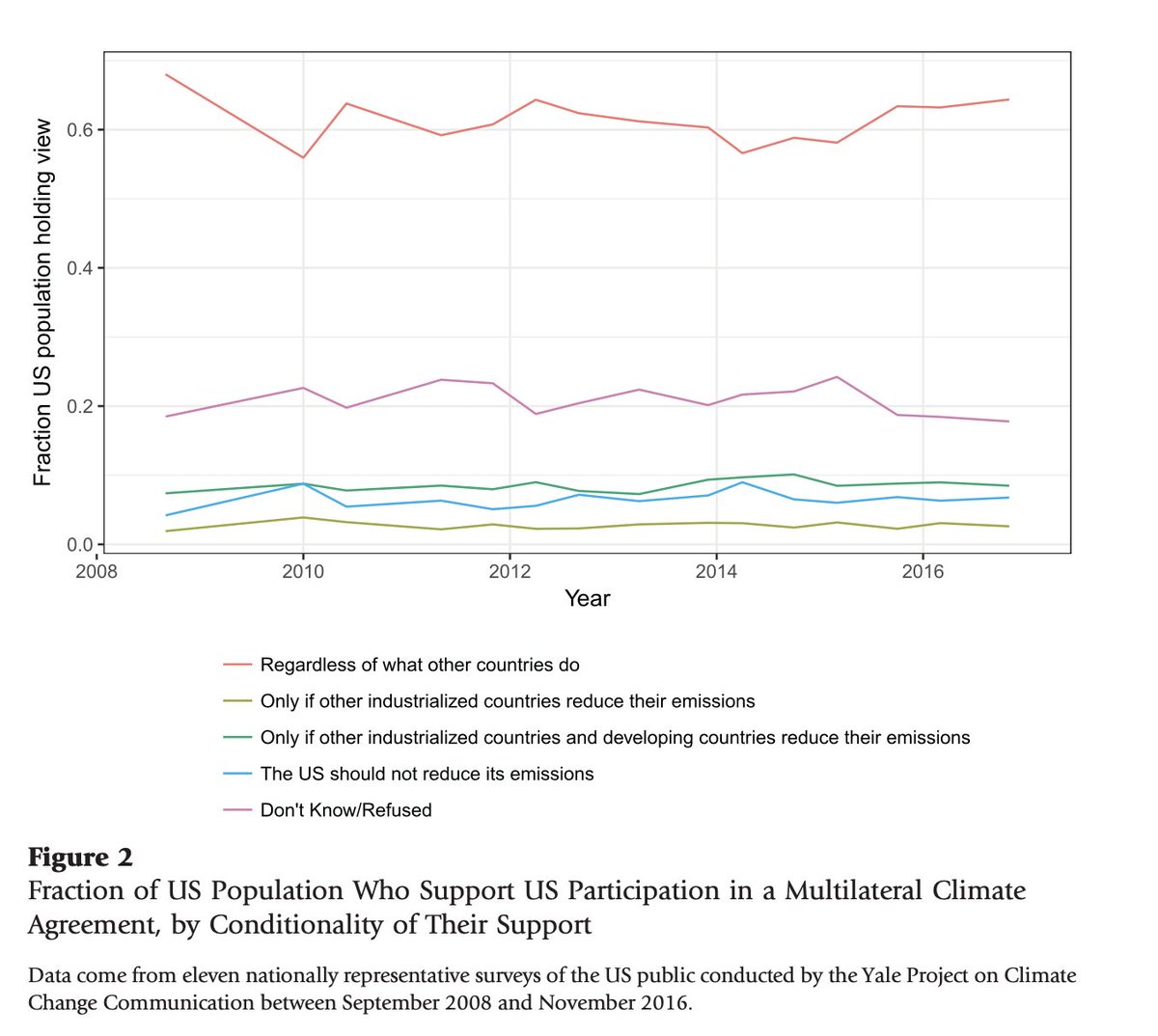

2⃣The public behaves like an unconditional climate cooperator! Most experiments and surveys do not find evidence that public support for action goes down in the presence of free-riding. Here is a US time-series courtesy of @YaleClimateComm as one example: 7/

3⃣National political actors also behave in a mostly unconditional fashion. For example, we revisit the Byrd-Hagel resolution and Bush's decision to reject Kyoto. We show that free-riding concerns were largely rhetorical, not substantive. 8/

In short, we can't actually locate any empirical evidence to suggest that free-riding in practice constrains global climate politics, even though policymakers and academics have blindly assumed this fact for decades. Much more on this in paper (and more nuanced too!). 9/

So what explains climate politics if not free-riding concerns? We think economic conflict between policy winners and losers is the real binding constraint on global climate politics. It can account for existing empirical evidence more completely *and* parsimoniously. 10/

Our provocation is also intended as an appeal to the wider community. Our work on this is ongoing - we want to know your most persuasive empirical evidence for free-riding in climate politics. Also, happy to share our paper if you don't have access. 11/

mitpressjournals.org/doi/full/10.11…

mitpressjournals.org/doi/full/10.11…

We've spent four decades assuming international institutions should primarily remedy free-riding. But maybe that's the wrong dilemma! Given the urgency of the threat, we can't risk our climate politics being a prisoner of the wrong theories. The stakes are too high. 12/12

PS: Our article leads a @GepJournal special issue addressing this need. First, a @thomasnhale article on "catalytic cooperation". Hale describes how a wide range of global problems can be addressed through the leadership of a proactive country.

mitpressjournals.org/doi/full/10.11…

mitpressjournals.org/doi/full/10.11…

Next, an article by @fgenovese86 and @pol_economist. Using survey experiments, they show that information about *domestic* distributional effects of climate policies is more valued by people than information about policy decisions abroad.

mitpressjournals.org/doi/full/10.11…

mitpressjournals.org/doi/full/10.11…

Finally, @khar1958 provides a careful comparative analysis of local politics in Canada and the United States and how it affects coal projects.

All three papers are terrific and worth a careful read.

mitpressjournals.org/doi/full/10.11…

All three papers are terrific and worth a careful read.

mitpressjournals.org/doi/full/10.11…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh