Okay, I'll do a proper thread on Khrushchev and Robert Frost. What a combination! First of all, although a great admirer of Frost's poetry, I never read his biography, so I don't know what he was doing in Gagra in 1962.

Gagra is a lovely little resort town just south of the Russian border in today's Abkhazia. Unfortunately, it was badly damaged in the civil war in the early 1990s (many of the formerly glorious palaces still stand abandoned, and overgrown with lush vegetation).

In the Soviet timies, Gagra was a summer destination for vacationers who would pack its many sanatoriums and the long beach. Khrushchev's villa was in Pitsunda, just south. He'd spent his vacations there and in fact was overthrown two years later while he was at Pitsunda.

Early in his tenure, Khrushchev often received completely random people (like groups of American tourists) but then he grew into the role and by the early 1960s, he'd only spare time for prominent politicians, businessmen, and public figures. Frost was one.

It was an interesting time. After declaring an ultimatum in 1958, where he tried to oust Western forces from West Berlin by concluding a peace treaty with the GDR, Khrushchev pedalled back. After the Wall was built in 1961, tensions began to die down.

But in September 1962 Berlin was still on everyone's mind - it was not even a year since the infamous tank standoff at Checkpoint Charlie, which highlighted the prospect of the Cold War turning quite hot in the heart of Europe.

Meanwhile, what Frost did not know was that the Soviets had been secretly shipping nuclear missiles to Cuba. Just weeks after this encounter, an American U2 would show them being installed in place. The world was about to live through its most dangerous moment in modern history.

Berlin was very much on Frost's mind when he saw Khrushchev. His thesis was that Germany was not important enough to fight a war over. "Neither you nor I want a united Germany," Frost said, so "don't let this simple question distract us from solving more important problems."

He later returned to this idea several times, saying at one point that there are only two countries in the world that matter - the US and the USSR. The others (including China, India, and all other countries) are just "trivial things, which should not be taken into account."

Khrushchev was quick to contradict this not very politically correct thesis, pointing out that China and India had a great future. On Germany, he peddled his standard line that the Americans had no right to West Berlin.

To demonstrate his point (and also to relate to Frost), he recounted an anecdote, where Leo Tolstoy told Maksim Gorky that whereas young people have both [sexual] desires and capabilities, as they grow older, they may still have the desires but not longer the capabilities.

America's "tragedy," Khrushchev said, was that it did not trim back its desires in line with its diminishing capabilities. Frost, however, predicted that the US would have enough capabilities to last for another 100 years.

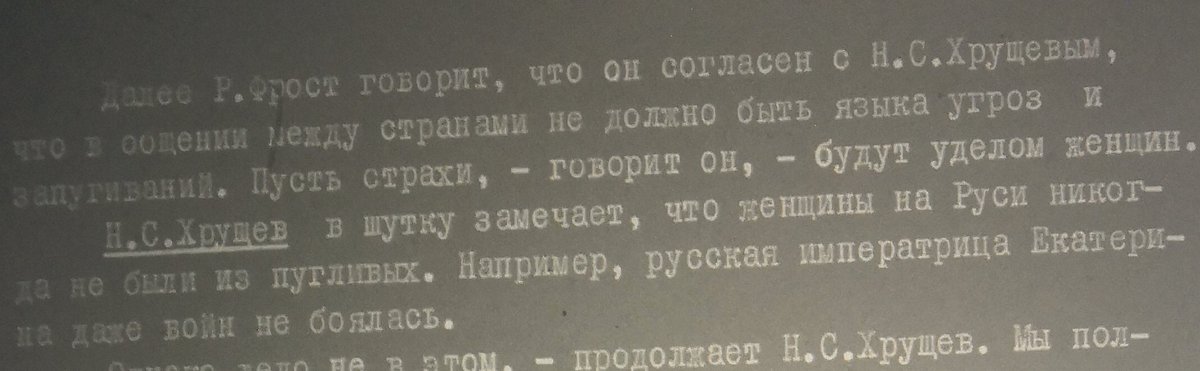

At one point, during the discussion of Berlin, Khrushchev said that it is impermissible for any country to resort to the language of threats (not bad for a guy who had kept Europe on the edge with his repeated ultimatums). There should be no fear, Khrushchev said.

Yes, Frost answered, there should be no fear. "Let fear be the preserve of women," he added. On hearing such gender bias, Khrushchev jumped in, saying that Russian women have no fear and that, for instance, Empress Catherine the Great, was not even afraid of war.

The big task that the US and the USSR should set themselves, Frost went on to argue, was to compete over the building of a democratic, humane society. He annoys Khrushchev by making reference to Communist brutalities.

Khrushchev retorts that Frost doesn't know anything about Communism, which is actually the most humane of all societies. When Frost brings up Stalinism, Khrushchev says that this page had been closed.

The conversation ends with Frost presenting Khrushchev with a volume of his poems with a hand-written note: "From your competitor in the sphere of friendship." Robert Frost died not quite four months after this encounter. /END/

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh