How can I read academic literature quick(er)?

Happy to share an academic #LifeHack

I talked to my students about this, today, I thought others might find it interesting, too.

I'll illustrate using a a paper by @benwansell

#AcademicTwitter #politicalscience #polsci

(Thread)

Happy to share an academic #LifeHack

I talked to my students about this, today, I thought others might find it interesting, too.

I'll illustrate using a a paper by @benwansell

#AcademicTwitter #politicalscience #polsci

(Thread)

Ok, let's see you open an article and you are like:

"Wait, whaaaaaaat 43 pages???"

"And it even contains maths!???!?11!"

So you can either

- switch to panic-mode

- you can drop the course & study program (please don't!)

- or you can read quicker

But how?

(2/n)

"Wait, whaaaaaaat 43 pages???"

"And it even contains maths!???!?11!"

So you can either

- switch to panic-mode

- you can drop the course & study program (please don't!)

- or you can read quicker

But how?

(2/n)

In my view, it is most important to know where the most important information is. You want that information.

You want the core info. But where is?

(3/n)

You want the core info. But where is?

(3/n)

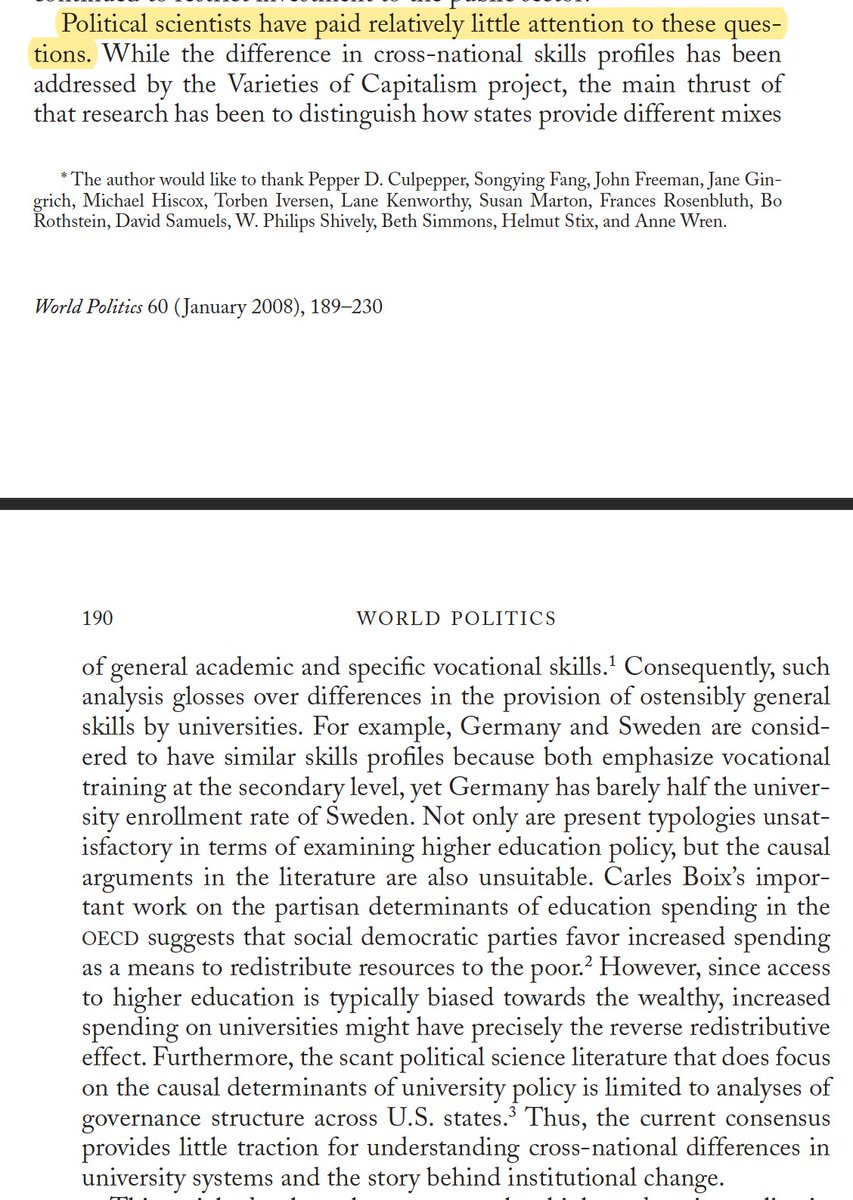

First point: It's not a novel. You can read the paper from the first word to the last - but that's not efficient.

An obvious point to look at is the abstract. Read the abstract first, then the introduction and conclusion. Then look at the details of the paper.

(4/n)

An obvious point to look at is the abstract. Read the abstract first, then the introduction and conclusion. Then look at the details of the paper.

(4/n)

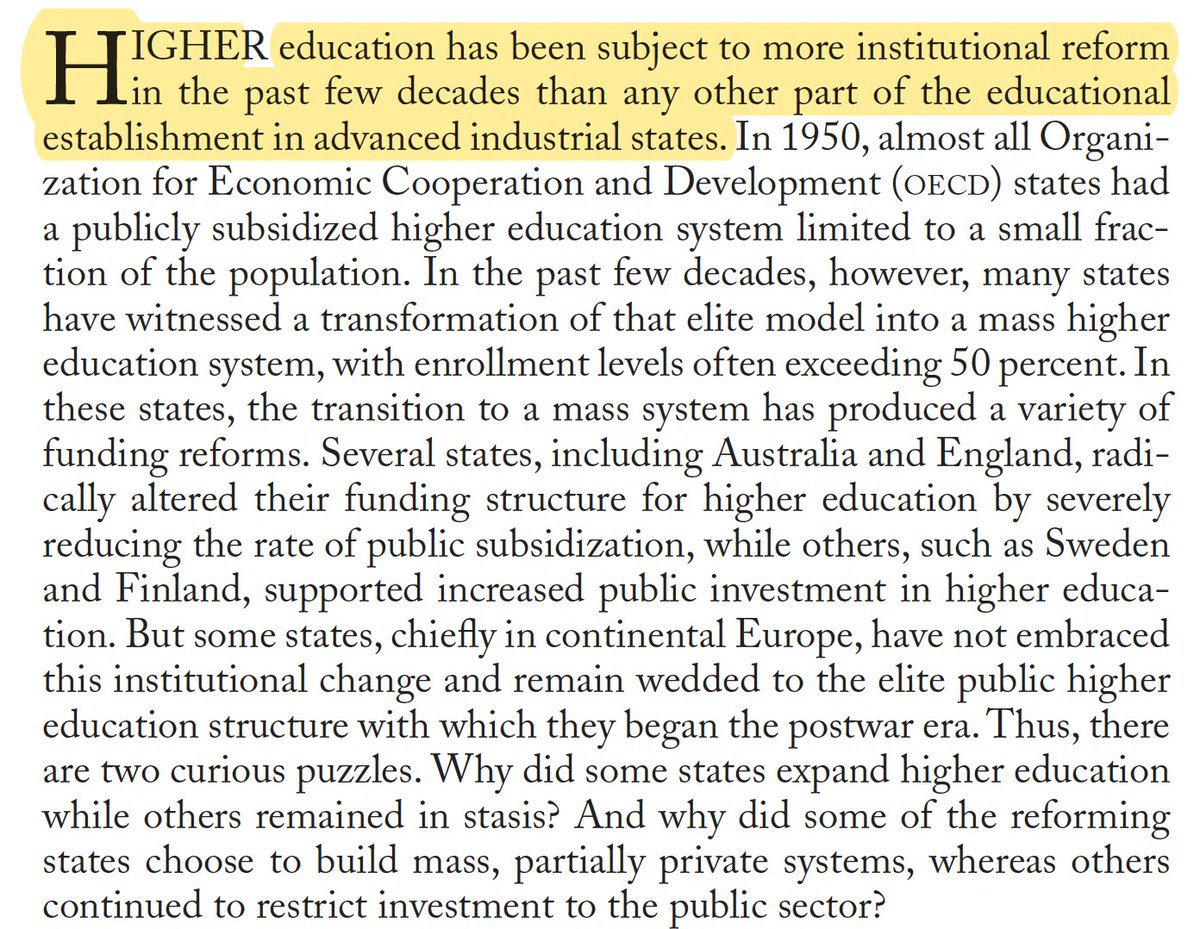

But my main point is more fundamental

The most important info is usually (at least with good writers like @benwansell) in the 1st sentence of every paragraph. Just read the first sentences of each paragraph first.

You will lack the details, but you will get the essence.

(5/n)

The most important info is usually (at least with good writers like @benwansell) in the 1st sentence of every paragraph. Just read the first sentences of each paragraph first.

You will lack the details, but you will get the essence.

(5/n)

... and so on.

Once you got the main story, you can (and should!) go back to the details.

- What's the mechanism?

- Why should this be the case?

- What's the evidence?

- Is the research design convincing?

- What literature is cited?

- ...

- etc

-> But all this comes 2nd.

(6/n)

Once you got the main story, you can (and should!) go back to the details.

- What's the mechanism?

- Why should this be the case?

- What's the evidence?

- Is the research design convincing?

- What literature is cited?

- ...

- etc

-> But all this comes 2nd.

(6/n)

Now, please don't misunderstand me as saying you can & should only spend a couple of minutes on reading literature. Please don't.

Do read carefully. But read efficient. It's not an analytical drama or poetry. It's a research article. -> Treat it like one!

(7/n)

Do read carefully. But read efficient. It's not an analytical drama or poetry. It's a research article. -> Treat it like one!

(7/n)

Finally, once you have got used to reading articles like this...

...start WRITING like this, too! When I write a text, I think about the 1st sentences of each paragraph. In my head I make a list of these "claims". And all I have to do afterwards is to "proof" each claim.

(8/n)

...start WRITING like this, too! When I write a text, I think about the 1st sentences of each paragraph. In my head I make a list of these "claims". And all I have to do afterwards is to "proof" each claim.

(8/n)

Let me know if this works for you and/or feel free to add more advice, I'd love to hear more perspectives on this and learn more, too.

(9/9)

(9/9)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh