Let’s talk about this story. It discusses a NJ bill that is designed to make sentencing less harsh. The bill is being held up because a lawmaker introduced an amendment that would eliminate the mandatory minimum for one type of corruption. nytimes.com/2020/12/17/nyr…

First, let's talk about the framing of the story. The lede is about how the lawmaker who introduced the amendment has a girlfriend whose son is facing corruption charges. The story minces no words: It says the amendment was added specifically to help that man.

The idea of powerful people helping each other escape punishment is a powerful one. It is the stuff of headlines and outrage, and so I'm not surprised that this is how the story is being framed.

But there is also another way to frame this story--that most people only appreciate the harshness and injustice of the criminal justice system once they or someone they love have been swept up in it.

We've seen the story before, and it sends us a different message.

We've seen the story before, and it sends us a different message.

The "powerful people get off" framing tells us to be suspicious of leniency & not to trust criminal justice reform.

The "I only realized when" framing tells us that we aren't paying enough attention to harshness & more reform is probably needed.

The "I only realized when" framing tells us that we aren't paying enough attention to harshness & more reform is probably needed.

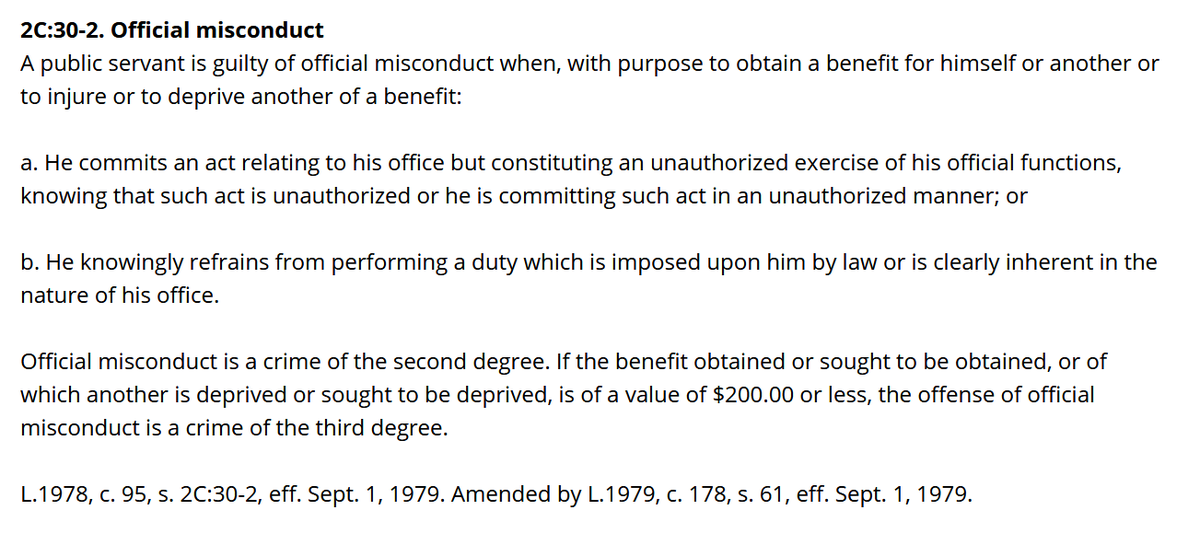

Second, let's talk about the crime itself which carries a 5 year mandatory minimum.

As someone who researches the statutory language of criminal laws, this law makes me very uncomfortable. The conduct is not well defined--look at that "clearly inherent" language. Yikes!

As someone who researches the statutory language of criminal laws, this law makes me very uncomfortable. The conduct is not well defined--look at that "clearly inherent" language. Yikes!

So it is unclear what, precisely, is illegal under this law. In addition, the law appears to be a kind of catch all -- other classic corruption crimes, like bribery, are handled by other statutes (which also carry mandatory minimums).

All of this raises an important question--Is this relatively vague law even necessary? Couldn't the girlfriend's son have been charged with some other crime, like theft?

And if we are going to have a relatively vague law, do we want it to carry a 5 year mandatory sentence?

And if we are going to have a relatively vague law, do we want it to carry a 5 year mandatory sentence?

That leads to my third point--all of the statements in the NYT story about why this mandatory minimum law is necessary. Those statements boil down to two arguments--neither of which stands up to scrutiny. The first argument is that officials "need" this law to "build cases"

In case it's not clear from these quotes, the argument about "building cases" is an argument that prosecutors need to be able to threaten suspects with a mandatory minimum sentence so that the suspect will plead guilty.

It's a common argument, usually framed in terms of "cooperation" rather than guilty pleas. (I guess prosecutors know that the public would balk at the idea that prosecutors shouldn't even have to bring a case to trial.)

The thing that is so galling about the "build the case" argument is that it is often paired with an argument about it being important that these defendants serve a particular sentence--even though the whole idea of cooperation is premised on the idea of a much lower sentence.

In this article, the argument is framed as a need for protection against politically appointed judges possibly being too lenient.

If the implication is supposed to be that judges as appointees can't be trusted, I wish it had mentioned that NJ prosecutors are selected the same way

If the implication is supposed to be that judges as appointees can't be trusted, I wish it had mentioned that NJ prosecutors are selected the same way

By supplementing the "build the case" argument with "judges might be too lenient," the article may mislead readers.

The article never mentions that mandatory minimums are about shifting power over punishment decisions from judges to prosecutors.

But that's exactly what they do.

The article never mentions that mandatory minimums are about shifting power over punishment decisions from judges to prosecutors.

But that's exactly what they do.

The second argument in favor of mandatory minimums is straightforward--both in terms of the argument and also why it is wrong.

The argument is deterrence. If you know crime X carries Y mandatory minimum, then you are less likely to commit crime X.

The argument is deterrence. If you know crime X carries Y mandatory minimum, then you are less likely to commit crime X.

The deterrence argument seems intuitive. The problem is that it doesn't actually happen.

The truth is that human beings don't really think like this. And the idea that people will be less likely to commit crimes because of higher punishments has been debunked lots of times.

The truth is that human beings don't really think like this. And the idea that people will be less likely to commit crimes because of higher punishments has been debunked lots of times.

The irony of this story is that this whole bill is about reducing mandatory minimum sentences. The amendment just added one more crime to the list. All of this bad arguments about keeping mandatory minimums apply to drug and property crimes as well.

It is precisely because of this that some people interviewed for the story were just like "OK. Feel free to another crime to the bill if you want."

Those people get it--mandatory minimums are not a good idea, even if you really don't like a particular type of crime.

Those people get it--mandatory minimums are not a good idea, even if you really don't like a particular type of crime.

But not everyone feels this way. Aside from prosecutors (and plenty of former prosecutors) who are always willing to recycle the same tired arguments in favor of mandatory minimums, there are other people opposed to this amendment: Progressives

Progressive groups are worried about money in government, corruption, and income inequality. I get it. I also worry about those things.

But the idea that removing a mandatory minimum sentence sends the message that a crime is "tolerated" is just silly.

But the idea that removing a mandatory minimum sentence sends the message that a crime is "tolerated" is just silly.

That "sends a message" argument is just as bad as the "build a case" argument and "deterrence" argument---and it has been used for decades to put more people in prison and to fuel mass incarceration.

These groups should know better.

These groups should know better.

Unfortunately, corruption specifically and white collar crime more generally is something where some progressives are happy to see higher penalties and a coercive justice system.

This desire for harshness is so prevalent, that some have coined the term "carceral progressivism"

This desire for harshness is so prevalent, that some have coined the term "carceral progressivism"

Don't get me wrong. There are reasonable arguments to be made about the underenforcement of white collar crimes and how particular underenforcement patterns appear designed to benefit the wealthy and the powerful.

https://twitter.com/CBHessick/status/1310537693584142336?s=20

But let's please not pretend that mandatory minimums are necessary to cure those enforcement problems. They exist in large part so that prosecutors do not actually have to prove their case in court. And they also just don't work.

And can we also agree that the Supreme Court's recent cases about how to interpret federal corruption statutes are just irrelevant to the conversation about whether states should have mandatory minimum penalties at their disposal to enforce poorly drafter state laws. Sheesh!!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh