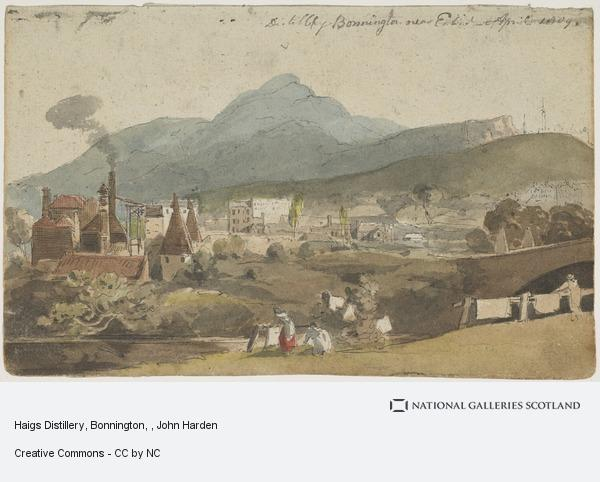

Our story begins with Patrick Miller of Dalswinton. He was born in Glasgow, the third son of minor gentry; William Miller of Glenlee (not Sir William, baronet), a Writer to the Signet, and Janet Hamilton (pic National Galleries of Scotland)

https://twitter.com/cocteautriplets/status/1340809183948664832

Patrick attended the University of Glasgow, where he decided (or it was decided for him) to take up banking as a profession. By the age of 29 he was a partner in the firm of William Ramsay of Barnton (independently wealthy from money his father made in the Canongate inns trade)

Ramsay was also a merchant, and Patrick spent much time looking after the shipping business of the firm. He is said to have learned first hand the perils of the sea, sparking an insatiable interest in naval architecture.

By the age of 36, Patrick was elected to the Court of the Bank of Scotland, where he was a reformer and a pioneer - instituting the practice of accepting the promisory notes of competitor banks. Both he and the bank prospered. (pic NGS)

Miller invested his wealth wisely in the furnaces of the Scottish industrial revolution and became one of the largest shareholders in the Carron Iron Company, one of the largest iron works in Europe.

Miller had expendable wealth, an interest in naval matters and with the technical might of the Carron Company at his disposal and at some point around 1785 or 86, he began to get seriously interested in the mechanical propulsion of boats

Miller began to experiment with double and triple-hulled model boats, with paddles between the hulls. He also began an acquaintance with one William Symington, an engineer who had been working on steam engines, trying to combine the best features of Watt and Newcomen's designs.

Now the dates get all a little unclear as lots of different things seem to be happening at once, but in 1785 Miller finances Symington to build a steam engine that would be suitable for propelling a boat.

By 1788, the steam engine has been perfected and fitted into a small twin-hulled boat, driving 2 paddles mounted between the hulls, and the intrepid gentlemen inventors make the first ever steam-propelled boat journey in the UK on Dalswinton Loch on Miller's estate.

The journey seems to have been successful, although it's unclear how practical this elaborate chain-driven catamaran powered by a relatively inefficient and slow operating engine really was. Miller soon lost interest anyway and moved on to other matters.

Miller was thinking bigger. Much, much, much bigger. He also either recognised the limitations (or couldn't be bothered with the complexities) of the immature steam engines.

In fact Miller was thinking of one of the biggest ships in the world. He and naval architect Alexander Naysmith drew up plans in Edinburgh in 1787 for a 246' long, 63' wide, triple deck, 5 masted, twin hulled warship armed with 144 guns. Oh and it had paddles between the hulls...

The paddles were to be turned by capstans, that is a load of sailors (30 per capstan infact), connected via mitre gears to the paddles. Miller claimed that under paddle-power his ship would make 4.3 knots.

The industrious Miller lost no time in sending out prospectuses to potential clients in the governments of Europe. Pitt's government in London refused to finance the scheme, but he was undeterred. Denmark sensibly said "Nej tak"

But King Gustav III happens to be at war with Russia in 1788 and after some embarrassing naval reverses, his interest is piqued by the idea that a paddle-assisted warship might be practical in the confines of the Baltic.

No problem says Miller, allow me to demonstrate to you THE POWER OF THIS FULLY ARMED AND OPERATIONAL PADDLE STATION

Because just to be sure, the year before Miller had gone ahead and paid for the construction of a 100' long, 2:5 scale prototype of his warship, built in Leith and known as "Experiment of Leith"

Experiment was already undertaking trials in the Forth by this time, where she is seen in the engraving below by J. C. Bourne.

Miller despatches the 5-masted Experiment to Sweden with all haste. At the time, Gustav III gives the prospectus from Miller to his chief naval architect and scientific advisor, Fredrik Henrik of Chapman, to cast his eyes across.

Chapman realises the vessel is far too large to support its own weight and would probably break in 2 when launched, and that the twin hulls and paddle system would make sailing against the wind almost impossible. He derides it as "the English (sic) Sea-Spook"

This leads to a potentially embarrassing situation, as Gustav III has been presented with a vessel for which he has no practical use and that he has been advised against using. Not wishing to upset Miller's generosity, he arranges for a suitable gift to be sent in payment.

So the King of Sweden generously sends Miller... a golden snuffbox. But he has a miniature of the "Experiment" painted on it, shown in Swedish colours anchored in Stockholm by the military stronghold of Skeppsholmen.

But, there's more. King Gustav had included a little surprise in the box, for Gustav knew that Miller's other passion in life was agriculture, and in the box was a small packet of seeds and a note to the effect of "plant me".

Miller duly planted the seeds back on his estate at Dalswinton and in 1791 is reputed to have made the first harvest in the British Isles of... Rutabaga, or for obvious reason - Swedish turnips!

The Swede, or "neep" in Scots (or "bagie" in particular parts of the Borders - from Rutabaga), became the best thing going since the potato was introduced (this was the time before sliced bread) and was a runaway success. All the gentlemen farmers wanted in on the action.

This is around 1791 and within a few years the Neep had cemented its place at the heart of Scottish cuisine. Co-incidentally, one Robert Burns happened to be a tenant of Miller at Dalswinton, and may or may not have been invited for a jolly on that first steamboat trip...

"The Experiment of Leith" was conveniently forgotten about, and was left tied up in Stockholm. She was sunk as the base of a bridge around 1794, but Miller didn't care, he was at home happy with his neeps.

A few years later, Lord Dundas picked up where Miller had left off, and funded Symington to build another steam paddle boat, using a much more practical engine. This became the "Charlotte Dundas", the first really practical and successful steamboat.

Patrick Miller lived out his days as deputy governor of the Bank of Scotland, and is buried in Greyfriars Kirkyard in Edinburgh

Footnote - the word Neep is not a contraction of Turnip, it's from the old English Næp from the latin Napus for... Turnip! It was an exceedingly important vegetable for winter fodder for livestock, and wasn't popularised in Burns' suppers until the late 19th. century

You may read the whole thread as a single, easy to consume page here; threadreaderapp.com/thread/1340960…

Footnote 2 - there's a really good PDF (in Swedish) about Experiment of Leith here, from where a couple of the pictures come from …storiskasamfundet.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/fn70_a…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh