A thread on the biomechanics of hip extension & how to train it

If you want to:

- Stand upright

- Sprint

- Train your glutes & hamstrings properly

You want to have hip extension. Problem is, majority of people & athletes don’t fully have it.

The reason why it’s often..

If you want to:

- Stand upright

- Sprint

- Train your glutes & hamstrings properly

You want to have hip extension. Problem is, majority of people & athletes don’t fully have it.

The reason why it’s often..

missing is for a few common reasons:

- Sitting too much: Sitting is hip flexion and the body will adapt to the demands placed on it

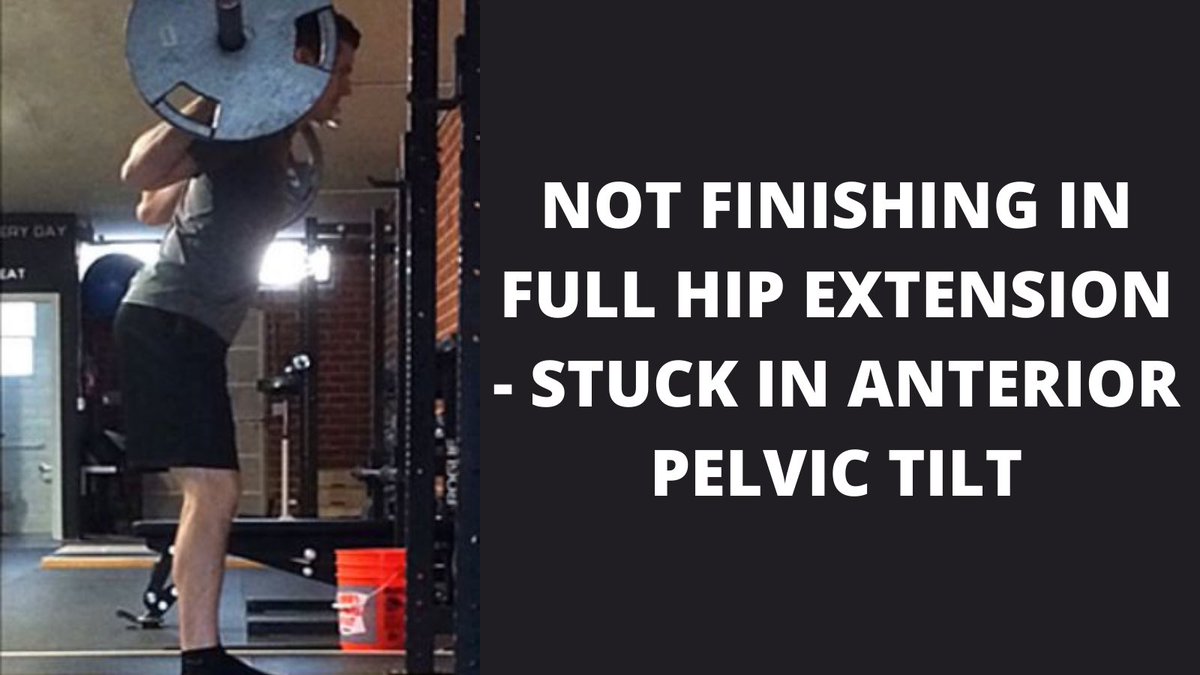

- Not training through a full range of motion. Ending your squats and deadlifts with your butt out means you’re not in full hip extension

- Sitting too much: Sitting is hip flexion and the body will adapt to the demands placed on it

- Not training through a full range of motion. Ending your squats and deadlifts with your butt out means you’re not in full hip extension

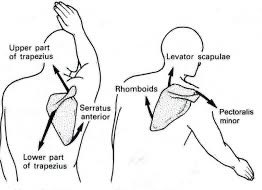

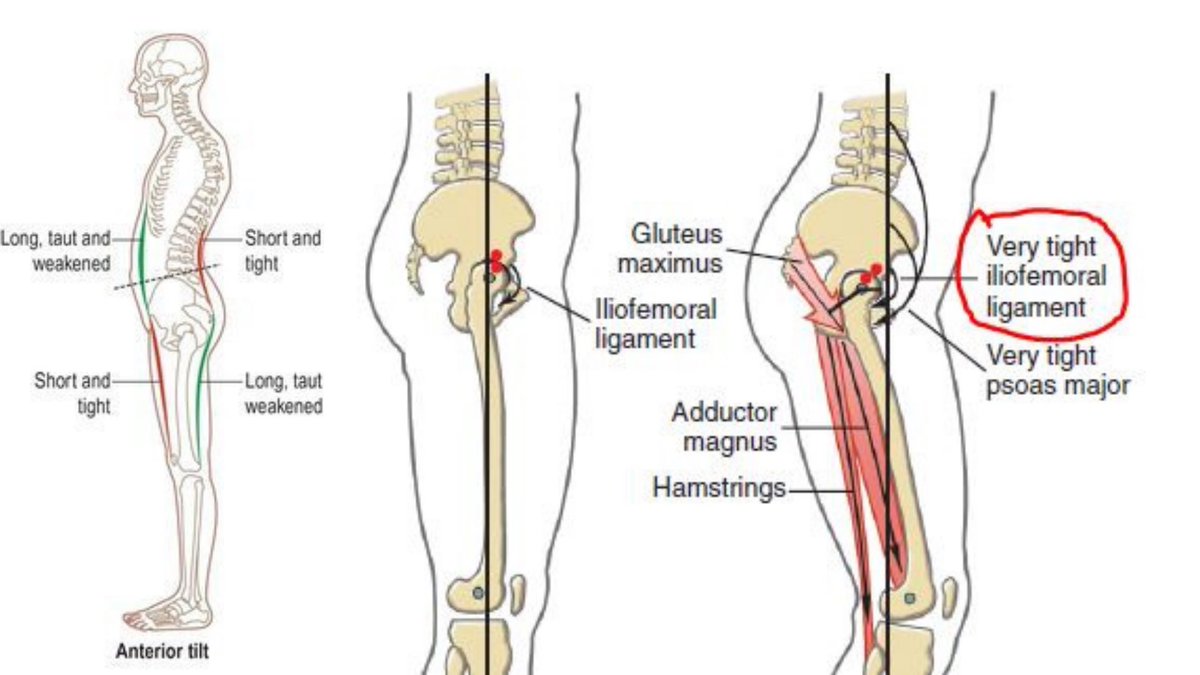

You’ll commonly see people who don’t have full hip extension stand in an Anterior Pelvic Tilt.

I think we know this tightens the hip flexors and back extensors, but it also tightens & restricts ligaments of the hips like the iliofemoral ligament.

This creates a hip flexion

I think we know this tightens the hip flexors and back extensors, but it also tightens & restricts ligaments of the hips like the iliofemoral ligament.

This creates a hip flexion

torque in the body which also increases the metabolic cost of standing, so your body will be spending more energy to keep you upright against gravity (Neumann, 2010).

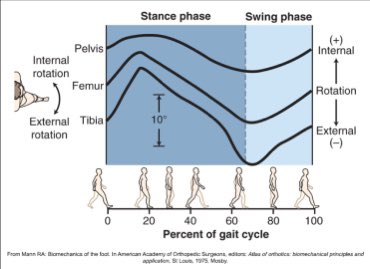

This also prevents the hamstrings & glutes to work adequately as hip extensors in gait & running, which causes

This also prevents the hamstrings & glutes to work adequately as hip extensors in gait & running, which causes

a poor “propulsive” phase of gait where we need hip extension to push us forward.

You’ll often see this manifest itself in butt-kicking/backside mechanics in sprinting, where you’ll see the back leg lag behind as they use lumbar extension as hip extension.

Credit: Cameron Josse

You’ll often see this manifest itself in butt-kicking/backside mechanics in sprinting, where you’ll see the back leg lag behind as they use lumbar extension as hip extension.

Credit: Cameron Josse

In order to easily assess it, lay on your side with your hips and knees bent.

Bring the top knee back and try to get it in-line with the hip, trunk, & head.

If you see low back arching before knee is in line, you’re using back extension to compensate for hip extension (3rd rep)

Bring the top knee back and try to get it in-line with the hip, trunk, & head.

If you see low back arching before knee is in line, you’re using back extension to compensate for hip extension (3rd rep)

If you’re missing hip extension on one or both sides, I like to start with the hamstrings & obliques as hip extensors as their attachments on the pelvis will also help re-orient their pelvis into a more neutral state as well.

This exercise is a good starting point:

This exercise is a good starting point:

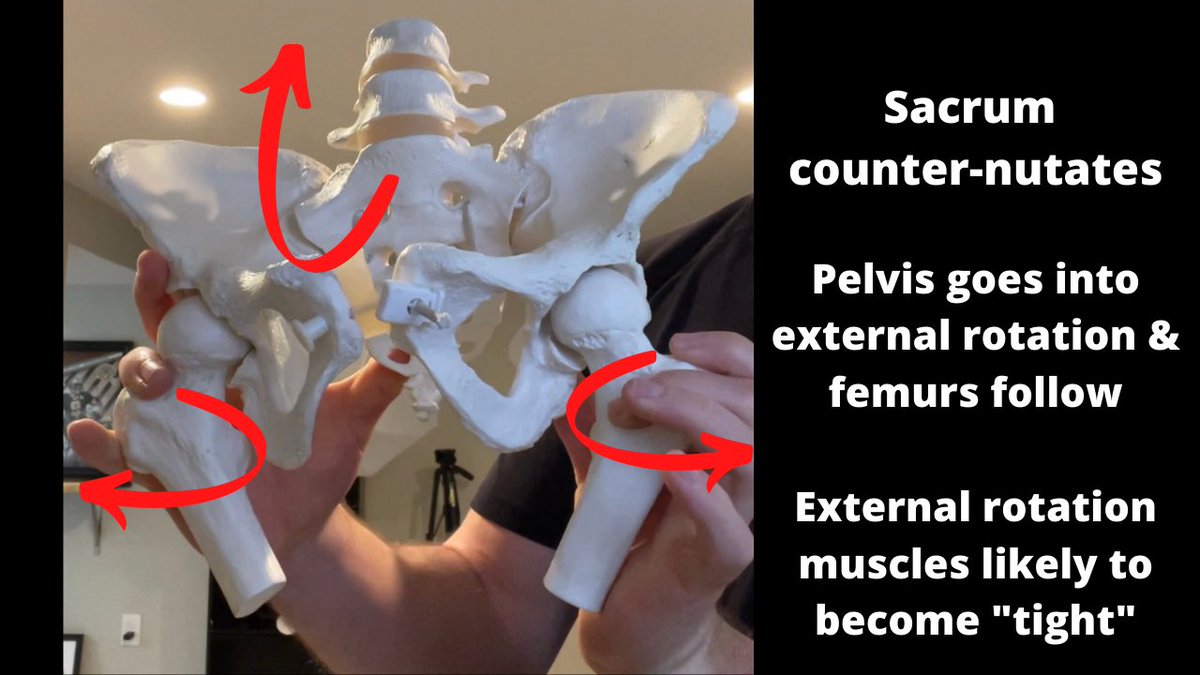

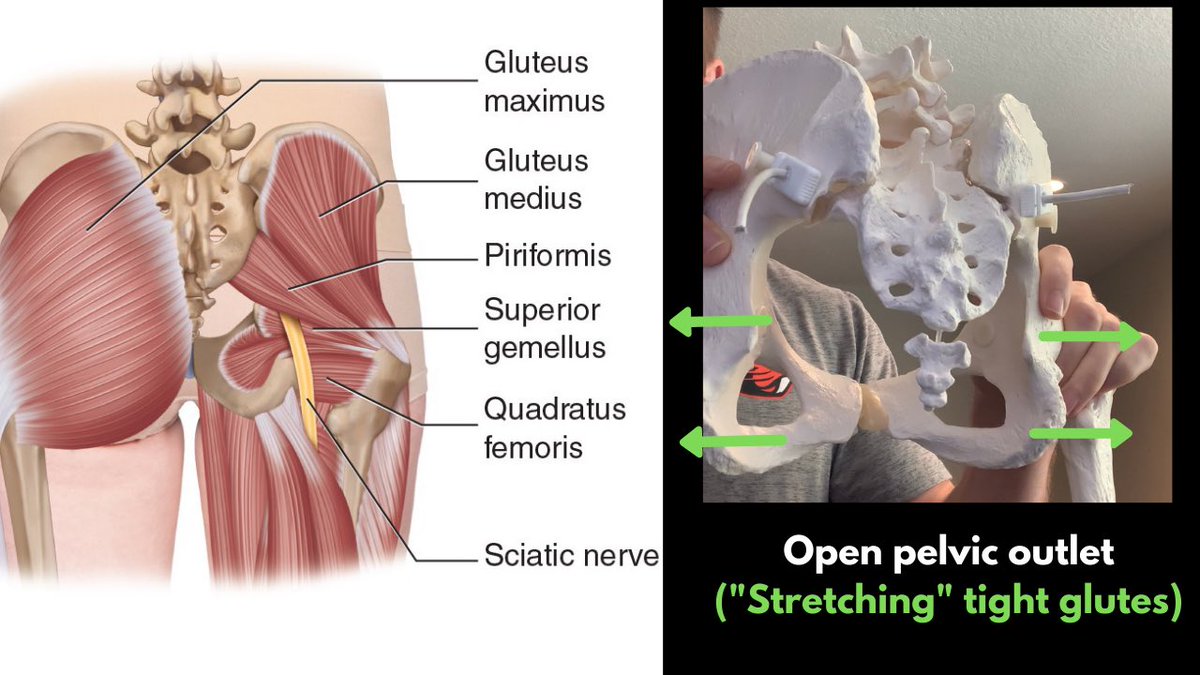

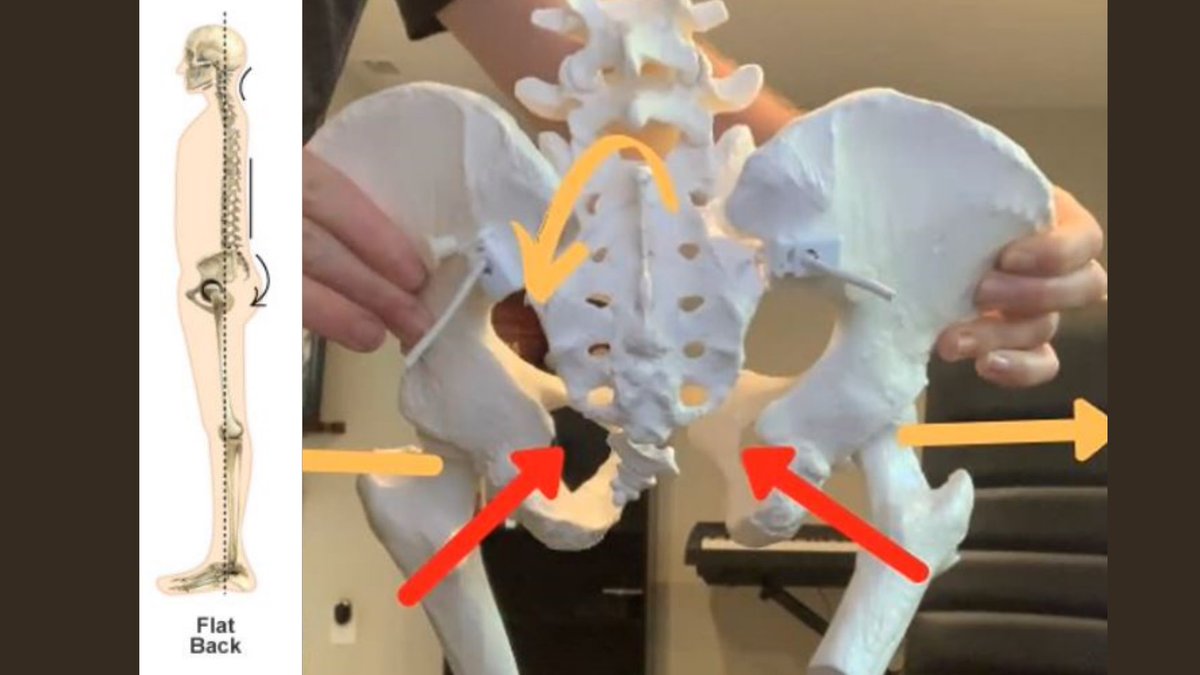

The reason why I sometimes don’t target the glutes first is because the glutes can actually be overly tight in someone with missing hip extension.

In this case, you’ll see them “butt gripping” where their glutes are always tight and trying to restrict their pelvis from

In this case, you’ll see them “butt gripping” where their glutes are always tight and trying to restrict their pelvis from

going too far forward so they essentially don’t fall on their face. You see this more commonly in people with flatter backs.

If this is the case, I like to actually loosen those glutes up via an approach like this:

If this is the case, I like to actually loosen those glutes up via an approach like this:

https://twitter.com/conor_harris_/status/1314684071637782528

Once they improve their sidelying hip extension test, the next step would be to train the pelvis through a full range of motion & provide a constraint to allow for the hamstrings & glutes to work together as they should to extend the hip.

Using a band around the waist is great:

Using a band around the waist is great:

Finally, make sure you finish your lifts in full hip extension as previously mentioned.

It’s important to “own” a range of motion that you have newly acquired through loaded exercises to provide context to the body so that it can withstand those positions under stress.

It’s important to “own” a range of motion that you have newly acquired through loaded exercises to provide context to the body so that it can withstand those positions under stress.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh