The new Variant Under Investigation (VUI) was re-designated Variant of Concern (VOC) 202012/01 on 18 December

This is an excellent report by @PHE_UK, but it’s a bit technical so I’ll try to unpick it for you

assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/upl…

1/14

This is an excellent report by @PHE_UK, but it’s a bit technical so I’ll try to unpick it for you

assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/upl…

1/14

The team at @PHE_uk begin by explaining that on 8 Dec they investigated the surge in cases in the South of England. Only 4% (255/6130) of Kent cases had genetic sequence data, but of these 117 genetically similar cases had been collected between 10-18 Nov

2/14

2/14

When looking at national data, these 117 cases were part of a larger cluster of 962 (to 8 Dec) in Kent, NE London, plus a few in rest London, Anglia, Essex

3/14

3/14

915 or the 962 cases had additional data: 828 were from November, 79 in Oct, 4 from Sept

90% were from <60 years old (further detail not yet available here)

6 patients had already died

4/14

90% were from <60 years old (further detail not yet available here)

6 patients had already died

4/14

As of 20 Dec, most cases were in London, the SE and East of England.

Of note, 3 of the main testing labs use a PCR test for 3 different viral genes: N, ORF1ab, S.

The new VOC has a mutation that makes this test negative for S (spike), but positive for the others.

5/14

Of note, 3 of the main testing labs use a PCR test for 3 different viral genes: N, ORF1ab, S.

The new VOC has a mutation that makes this test negative for S (spike), but positive for the others.

5/14

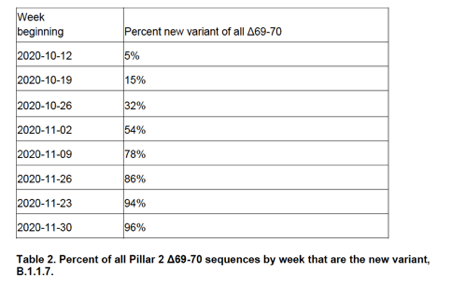

This 'S-gene target failure' (SGTF) proved useful because 97% of pillar 2 (non-hospital) PCR tests negative for S, but positive for N and ORF1, were this VOC. Using this, it was possible to calculate that VOC is more transmissible, adding about 0.5 to the R value

6/14

6/14

We can see here, the proportion of SGTFs in positive tests at one Lighthouse lab. Early on, low level SGTFs were seen due to other strains(blue line), then from Nov the new VOC (red line, also called B.1.1.7) rapidly began to dominate the positive tests

7/14

7/14

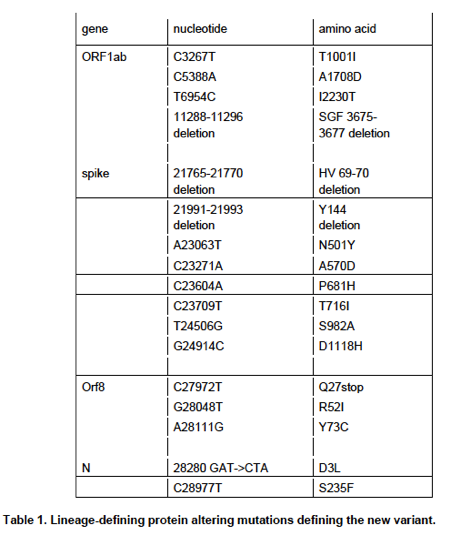

The new VOC is defined by having 23 mutations.

Because of the way genetics works, 6 of these don’t actually change viral proteins (so-called synonymous mutations).

13 change amino acids of a viral protein (see Figure)

4 remove a small piece of a protein

8/14

Because of the way genetics works, 6 of these don’t actually change viral proteins (so-called synonymous mutations).

13 change amino acids of a viral protein (see Figure)

4 remove a small piece of a protein

8/14

Because this VOC has acquired an unusually large number of mutations, seemingly in one step, it is speculated that it might have arisen either in 1 person with a weak immune system (next tweet) or even in another animal (as happened with the Danish cluster involving mink)

9/14

9/14

For example, recently a patient on immunosuppressive drugs remained infected (with a different variant) for 154 days before dying. During that infection, the virus acquired many new mutations

www-nejm-org.ezp.lib.cam.ac.uk/doi/full/10.10…

10/14

www-nejm-org.ezp.lib.cam.ac.uk/doi/full/10.10…

10/14

N501Y mutation in the S protein of B.1.1.7 & the deletion 69/70 may account for much of its the transmissibility. N501Y is known to increase binding to ACE2, a protein on our cells the virus uses to gain entry. N501Y appears to allow the virus to infect mice too.

11/14

11/14

501 is where neutralising antibodies often act, so it's possible that N501Y might affect such antibodies.

Although N501Y has not yet been tested, other mutations at 501 decrease the effectiveness of LYCoV016, a monoclonal antibody developed to treat COVID19

12/14

Although N501Y has not yet been tested, other mutations at 501 decrease the effectiveness of LYCoV016, a monoclonal antibody developed to treat COVID19

12/14

There is no information about natural antibodies, which, because of their diversity, target many parts of a virus at once. But, vaccination generates lots of different antibodies, so is less likely to be adversely affected.

13/14

13/14

There is much still to understand about this variant, but the speed of progress by @PHE_uk and @CovidGenomicsUK is nothing short of breath-taking.

They deserve our thanks!

14/14

They deserve our thanks!

14/14

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh