If we can get emissions down to zero (or net-zero), the planet will likely stop warming. Good @guardian piece covering this issue – which is well understood by the scientific community but often missed in public discussions. theguardian.com/environment/20… 1/6

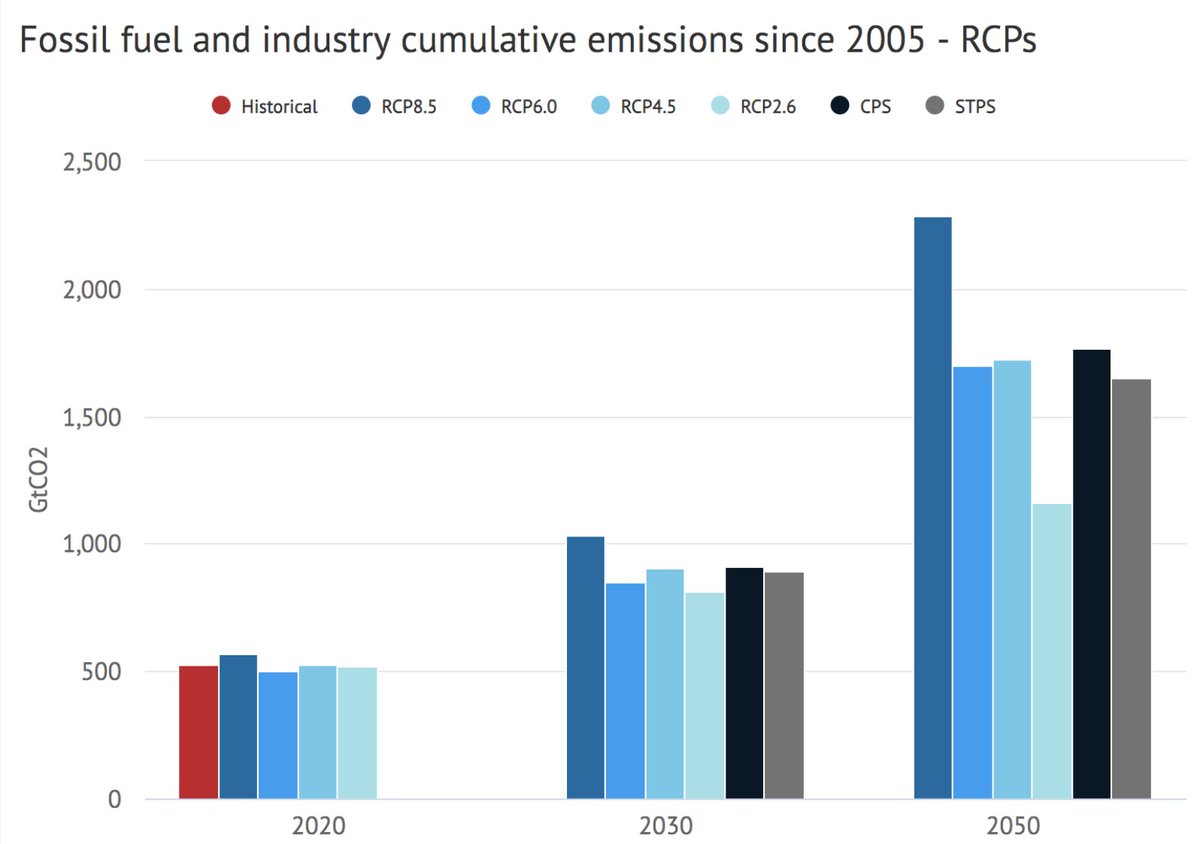

This is good news, because it means that warming that occurs this century is almost entirely under our control. We can decided how much CO2 and other greenhouse gases we emit, and the climate will respond accordingly. 2/6

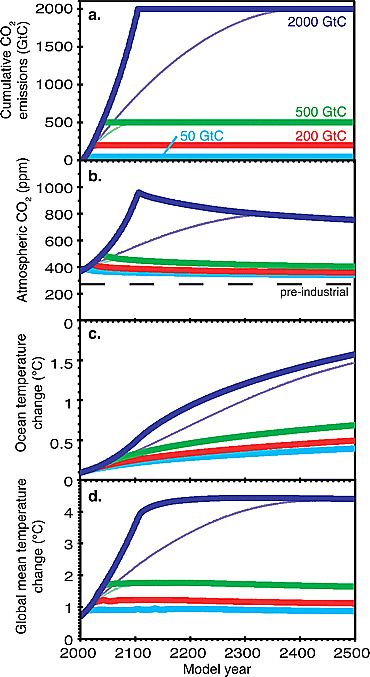

However, the downside of this finding is that even if we get emissions all the way down to zero, temperatures will not fall, at least for the next few centuries. Without net-negative emissions climate change is largely irreversible. 3/6

Part of the public confusion around committed warming (or warming "in the pipeline") comes from people conflating scenarios with constant concentrations and those with zero emissions:

https://twitter.com/hausfath/status/13465265678711029794/6

Theres some nuance and uncertainty here, as with all earth system science; for example, if current temperatures are lower due to natural variability (e.g. pattern effects in the Pacific), there could be some additional warming if or when that reverses:

https://twitter.com/hausfath/status/13461603149249740815/6

But our models are pretty consistent in showing that, once emissions get to zero or net-zero, temperatures remain flat for the next few centuries (+/- a few tenths of a degree): biogeosciences.net/17/2987/2020/ 6/6

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh