Thank you so much to the incredible @gregjenner and his team for having me on "You're Dead to Me" and to @kaekurd for being so hilarious and bringing Gilgamesh the restaurant into my life!

Here’s a thread of some of the stuff referenced in the podcast for those interested

Here’s a thread of some of the stuff referenced in the podcast for those interested

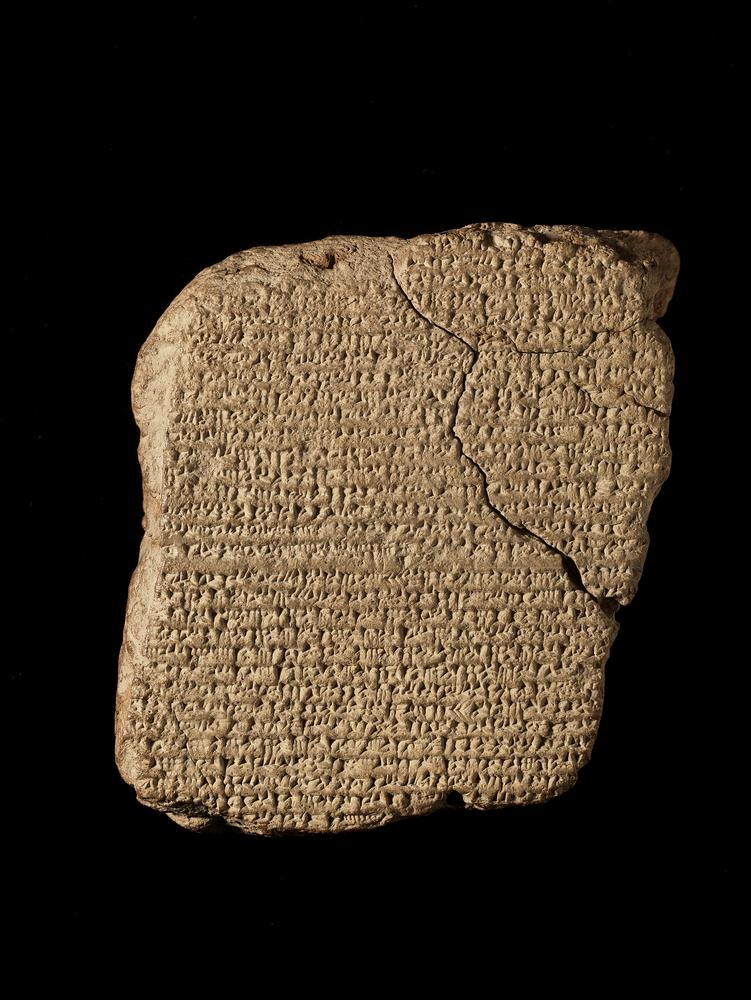

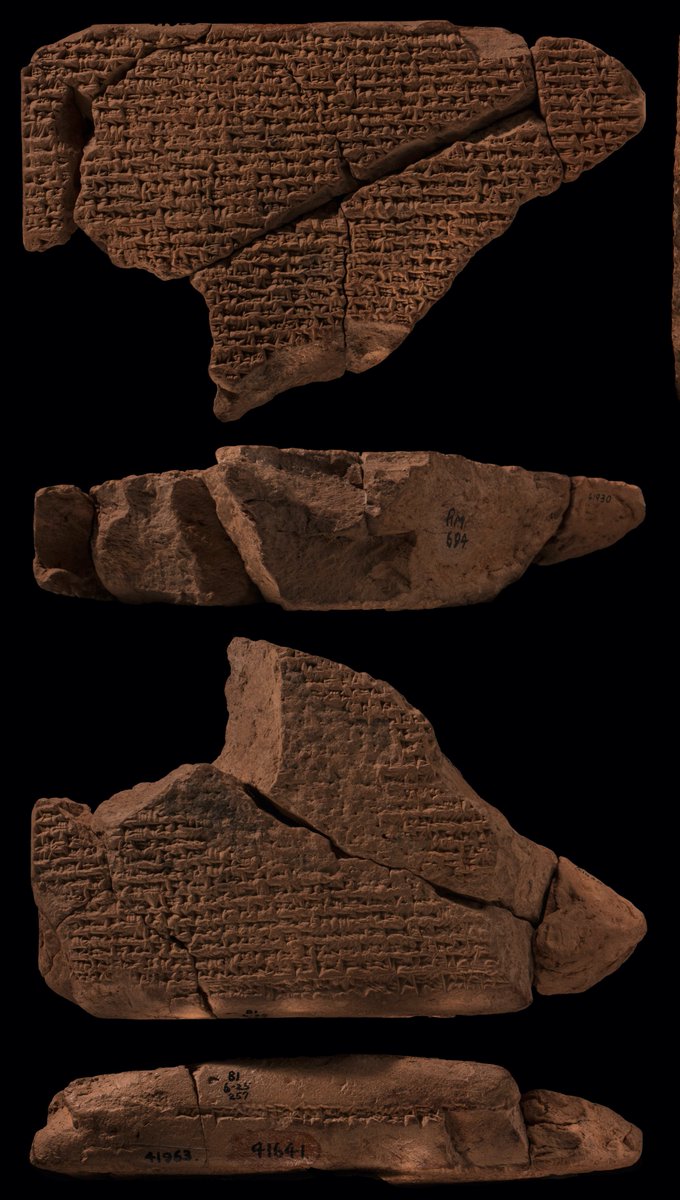

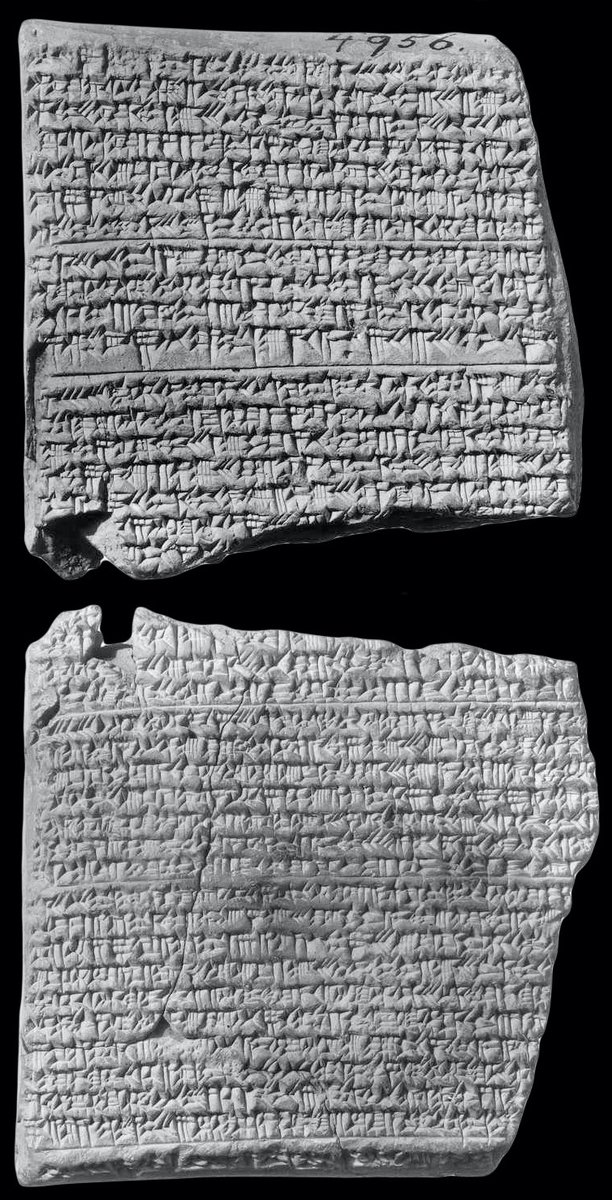

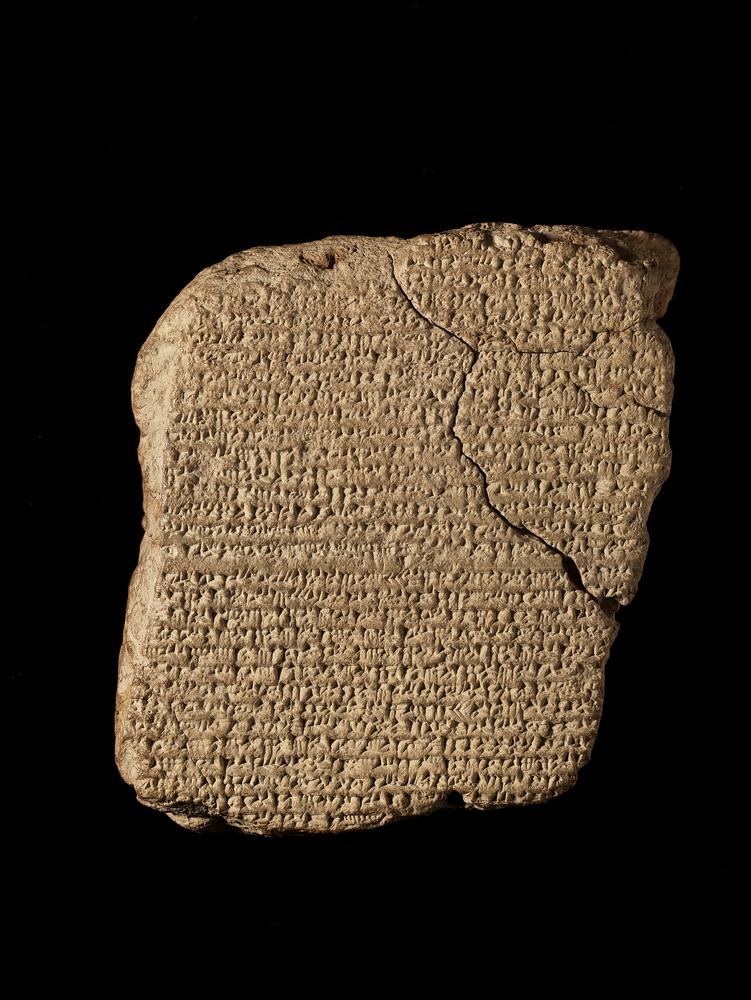

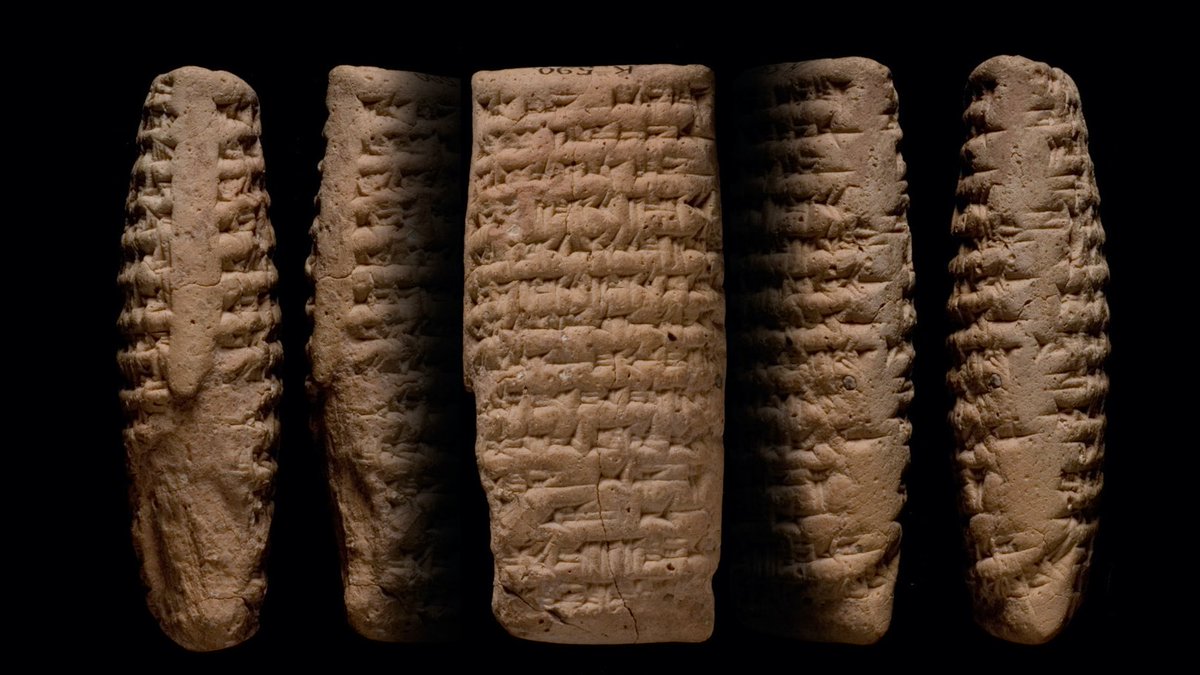

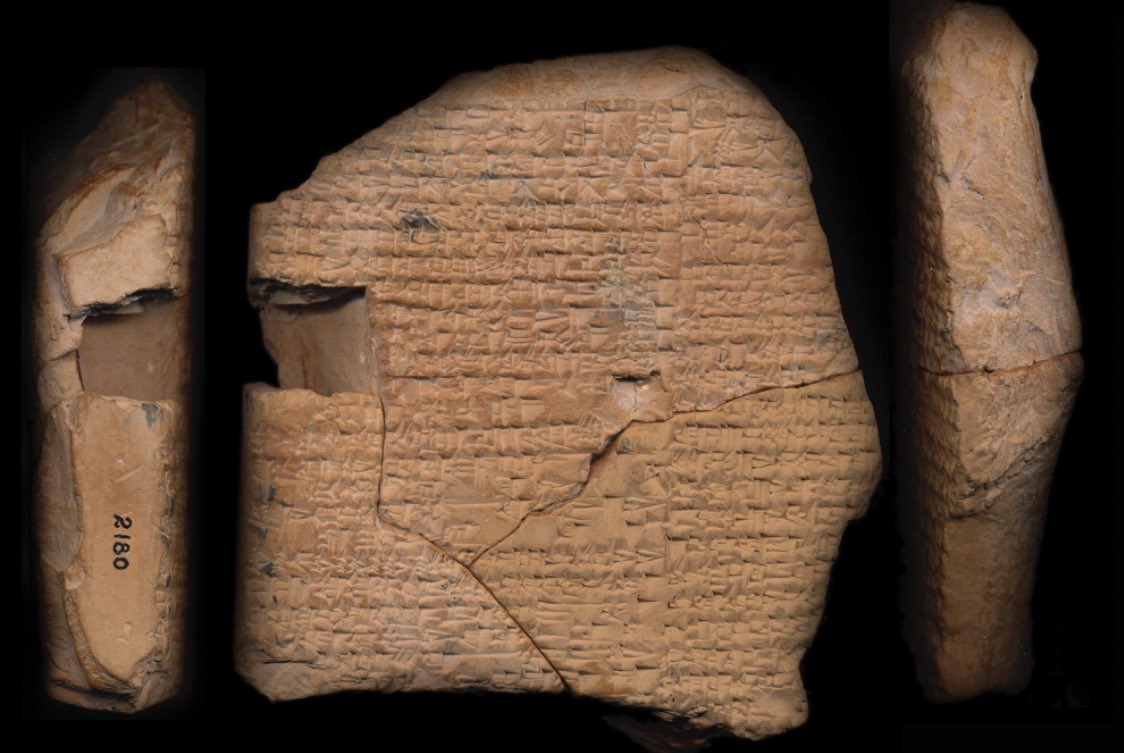

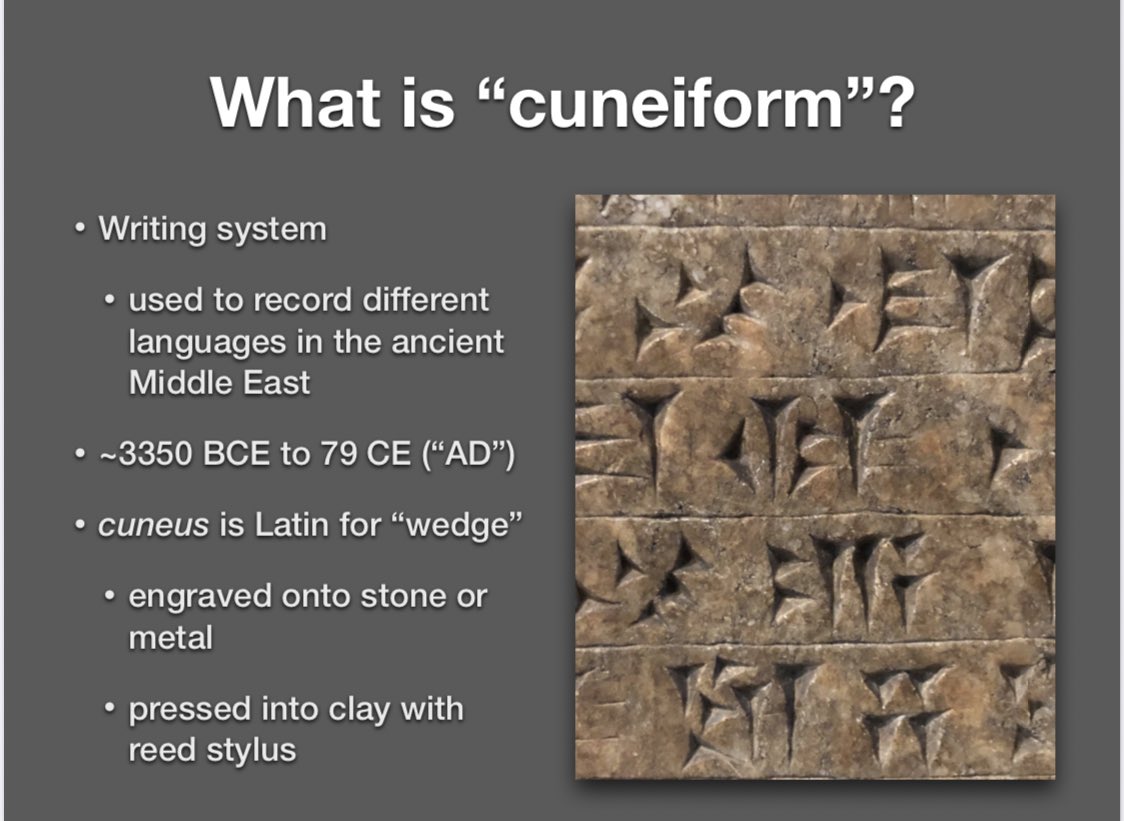

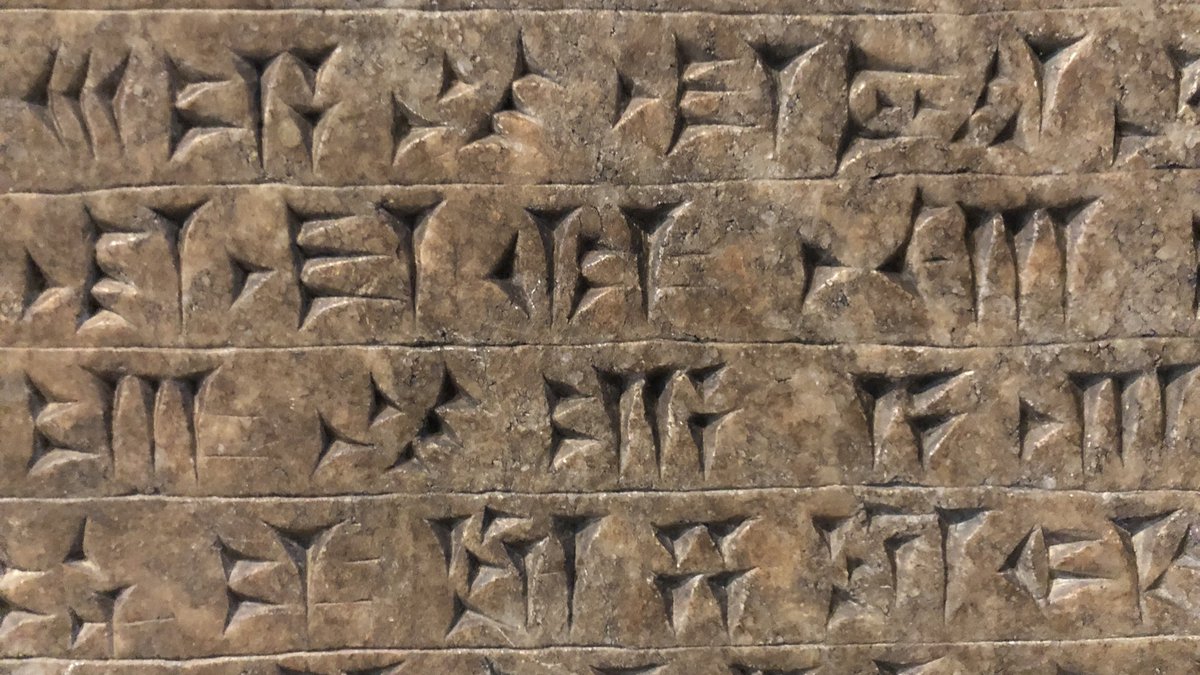

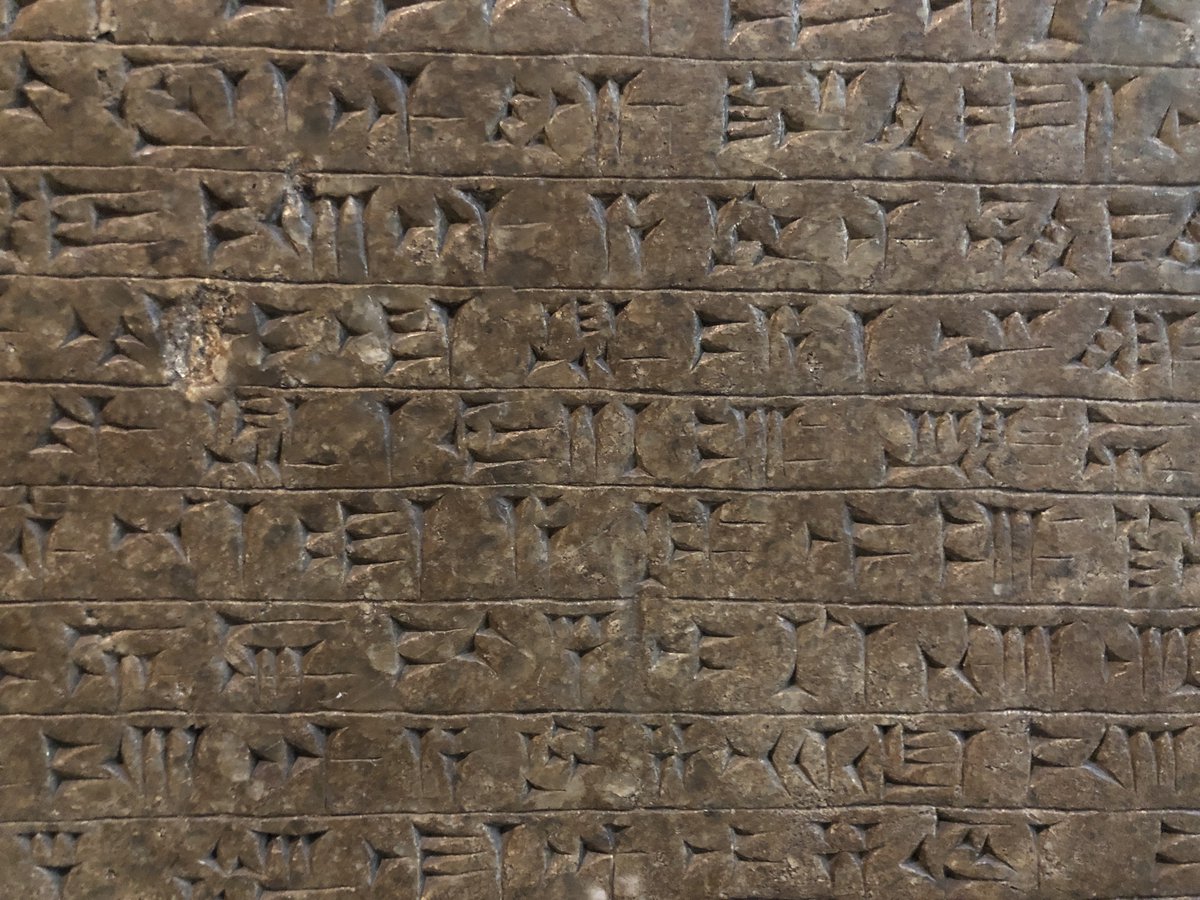

First of all, what even is cuneiform?

It’s a writing system from the ancient Middle East, used to write several languages like Sumerian and Akkadian. Cuneiform signs can stand for whole words or syllables. Here’s a little primer of its evolution sites.utexas.edu/dsb/tokens/the…

It’s a writing system from the ancient Middle East, used to write several languages like Sumerian and Akkadian. Cuneiform signs can stand for whole words or syllables. Here’s a little primer of its evolution sites.utexas.edu/dsb/tokens/the…

What kinds of texts was cuneiform used to write?

Initially, accounting records and lists.

Eventually, literature, astronomy, medicine, maps, architectural plans, omens, letters, contracts, law collections, and more.

Initially, accounting records and lists.

Eventually, literature, astronomy, medicine, maps, architectural plans, omens, letters, contracts, law collections, and more.

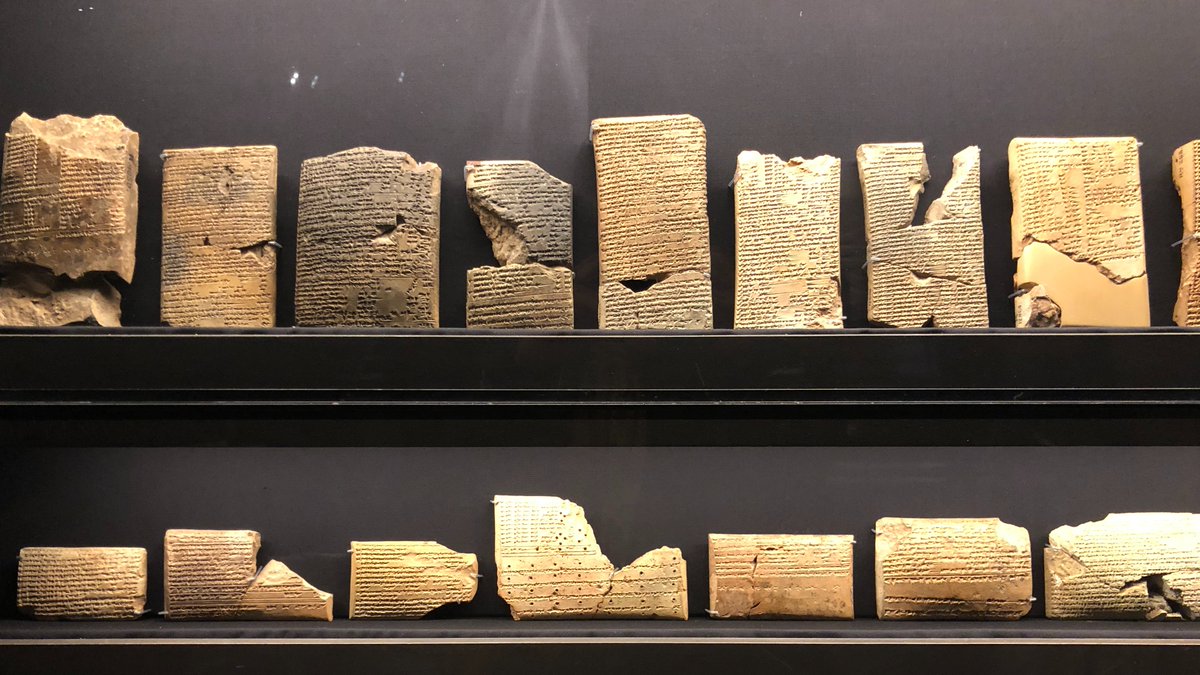

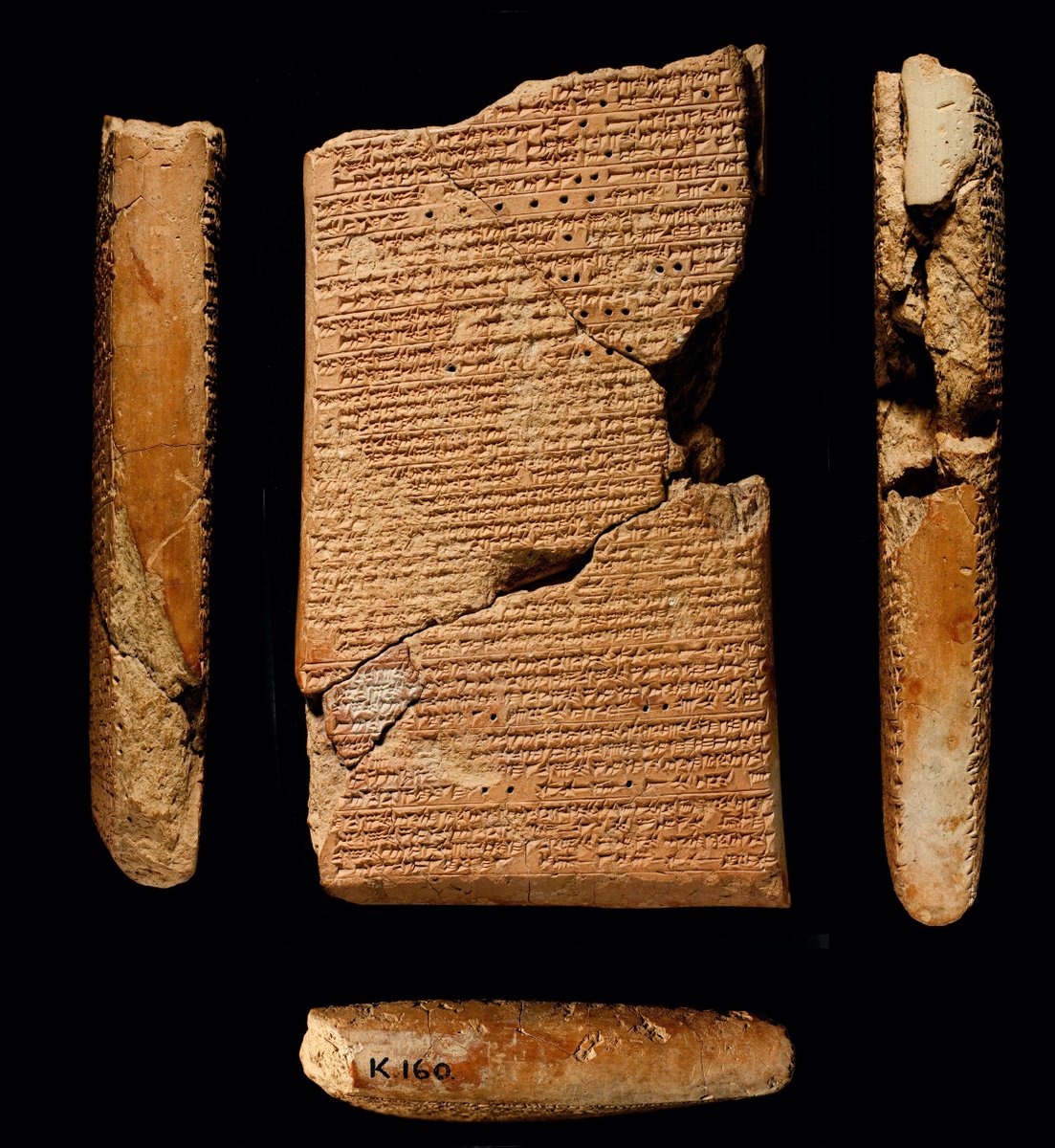

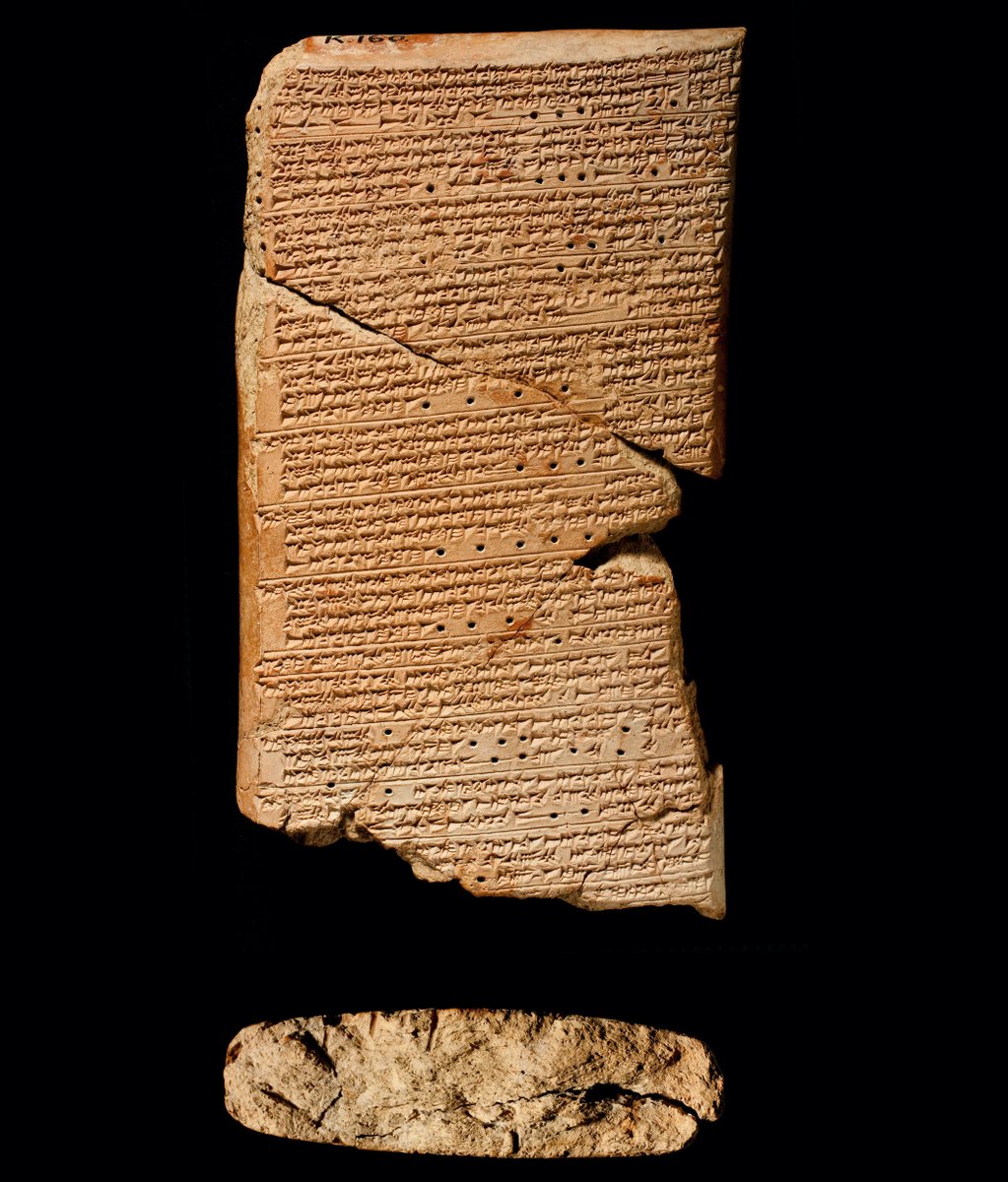

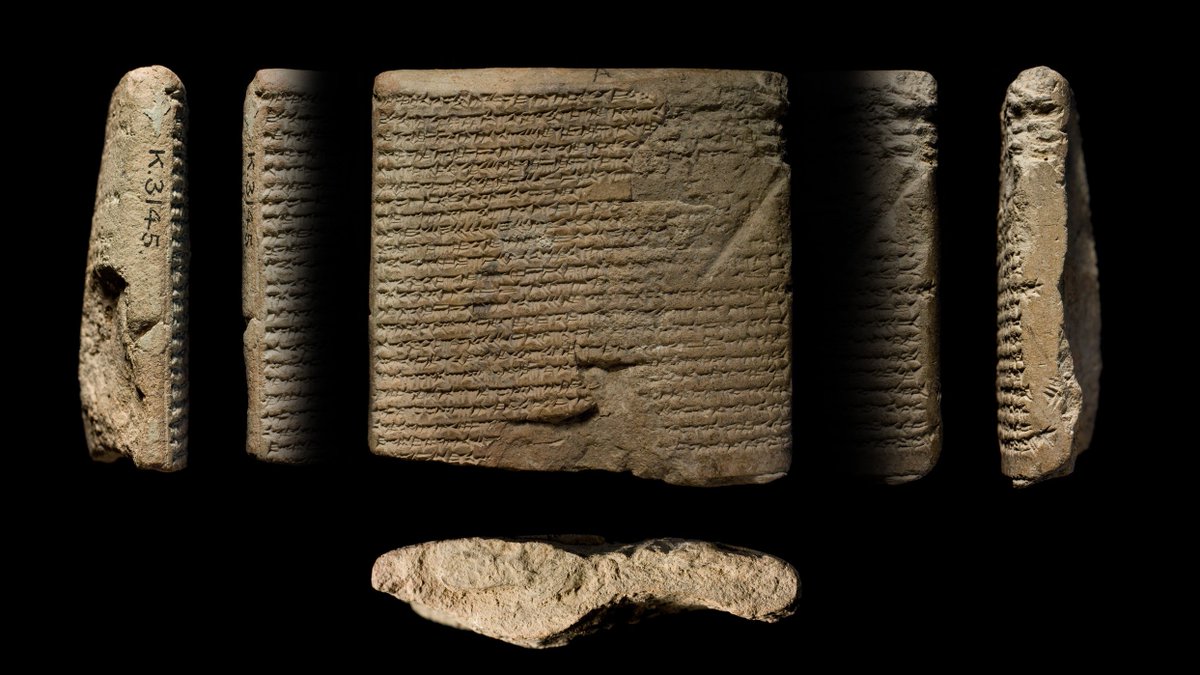

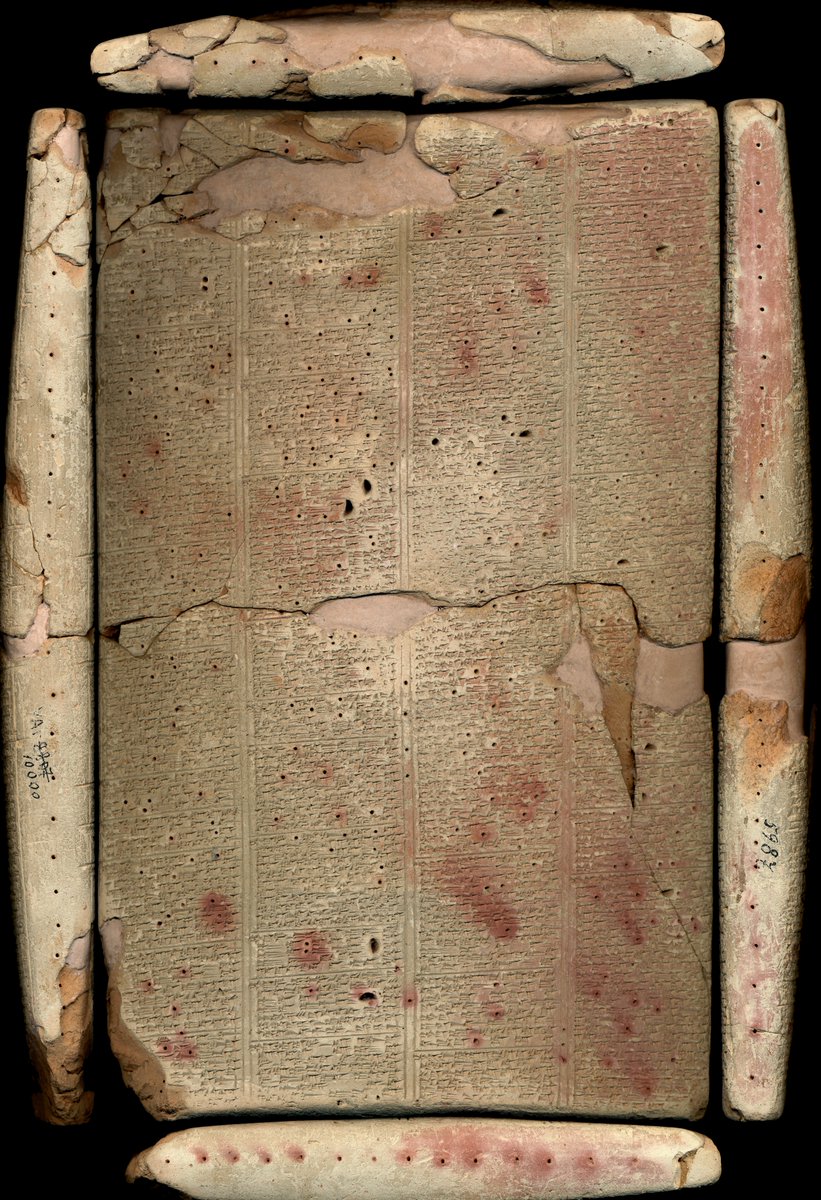

Texts from the Library of Ashurbanipal, who ruled the ancient Assyrian empire when it was at its largest in the 7th century BCE, represent many of the genres of cuneiform texts and scholarship.

Here’s a short intro to the library via @opencuneiform oracc.museum.upenn.edu/asbp/whatisthe…

Here’s a short intro to the library via @opencuneiform oracc.museum.upenn.edu/asbp/whatisthe…

The Library of Ashurbanipal has a complicated modern and ancient history, which you can read about in this brilliant (and open access) book by Prof @Eleanor_Robson uclpress.co.uk/products/125022

One of my favourite clay tablets from the Library of Ashurbanipal is this star map for the night of 3-4 January 650 BCE, including the constellation Gemini britishmuseum.org/collection/obj…

One clue about the long history of “astronomology” (h/t @willismonroe) in ancient Mesopotamia was found in the Library of Ashurbanipal. The “Venus Tablet of Ammisaduqa” is a copy of observations of Venus from ~1000 years earlier that’s also part of a larger textbook of omens.

Here’s a dated but open access translation of the Venus Tablet of Ammisaduqa by the late Dr Erica Reiner caeno.org/_Eponym/pdf/Re…

The main tool used in astronomy in ancient Mesopotamia ended up being…maths!

Read about learning math and science in the ancient Middle East in this fascinating piece by Prof @Eleanor_Robson including a discussion of this geometry textbook from 1750 BCE aaas.org/sites/default/…

Read about learning math and science in the ancient Middle East in this fascinating piece by Prof @Eleanor_Robson including a discussion of this geometry textbook from 1750 BCE aaas.org/sites/default/…

Okay quick break because there are a lot more tweets to follow in this thread but I gotta feed a baby first

Okay I have no idea where I was going with this, so we're just gonna move on to plaques.

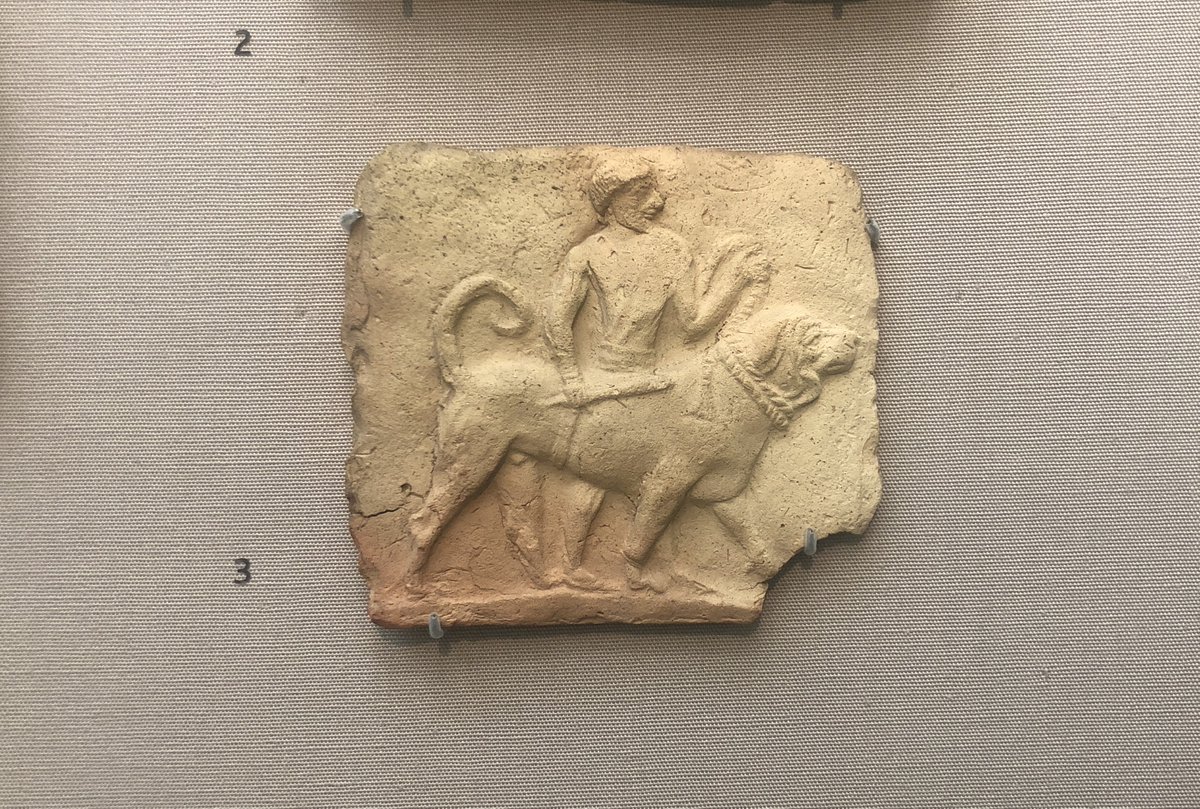

Some of my favourite artefacts from ancient Mesopotamia are these mass-produced plaques that show scenes from everyday life, like breastfeeding and dog walking, and mythological beings.

They’re honestly lovely, and I’m sorry my terrible photography skills don’t do them justice

They’re honestly lovely, and I’m sorry my terrible photography skills don’t do them justice

There are several clay plaques from ancient Babylonia that show people drinking what is probably beer through a straw while engaged in sexual activity (let’s not forget that these artefacts were made by human beings).

britishmuseum.withgoogle.com/object/plaque-…

britishmuseum.withgoogle.com/object/plaque-…

“And I, through your love and good love-making, I find refuge again and again,” reads the last line of an Old Babylonian love incantation.

Some are graphic, some creepy, some sweet. All speak to a relatable desire for love. You can peruse them here: oracc.museum.upenn.edu/akklove/corpus

Some are graphic, some creepy, some sweet. All speak to a relatable desire for love. You can peruse them here: oracc.museum.upenn.edu/akklove/corpus

Moving on to my favourite subject aka medicine in ancient Mesopotamia

The key medical professionals in ancient Mesopotamia were the asû “physician” and the ashipu, “exorcist”.

If you want to learn more about them, an excellent discussion appears in @PankTroels's open access book on a doctor named Kisir-Ashur humanities.ku.dk/news/2020/new-…

If you want to learn more about them, an excellent discussion appears in @PankTroels's open access book on a doctor named Kisir-Ashur humanities.ku.dk/news/2020/new-…

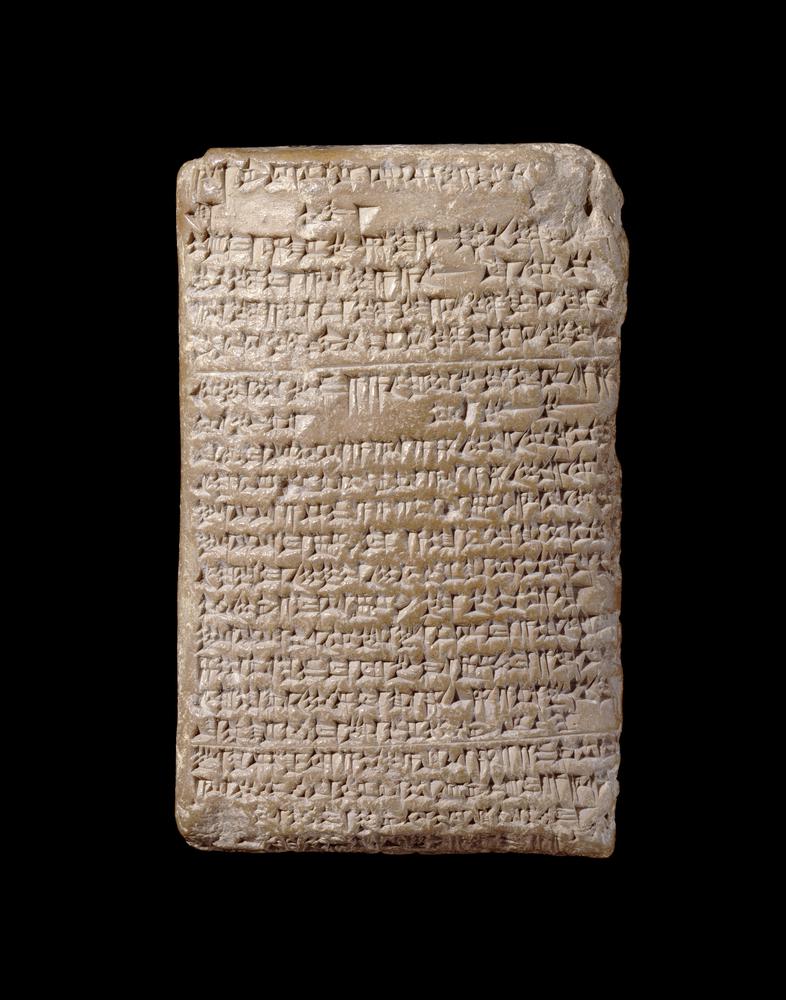

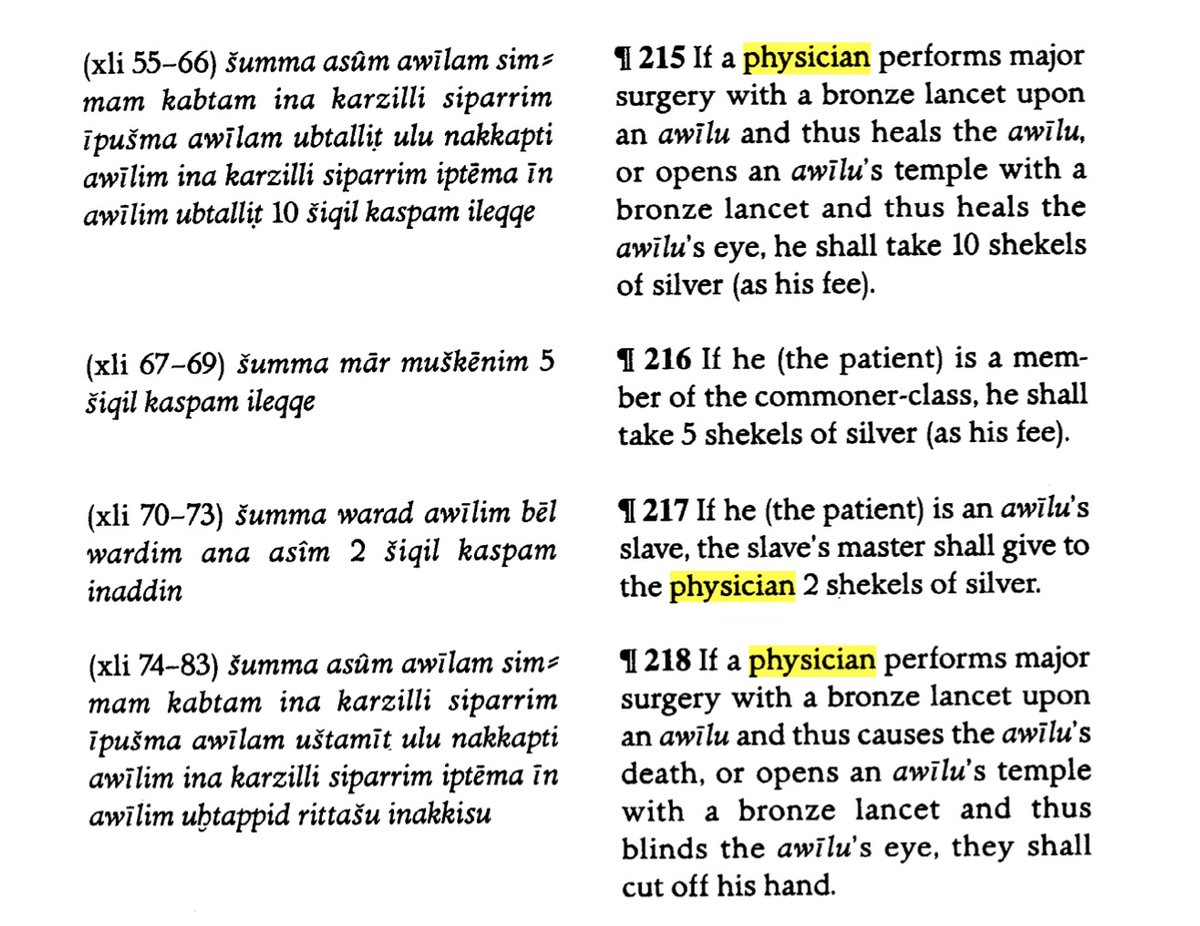

Hammurabi’s law collection includes provisions that deal with fees (and punishment) of physicians, though it's unclear clear if, how, or when these “laws” were applied.

E.g., physician who performs successful surgery on a member of the awilum class is paid 10 shekels of silver.

E.g., physician who performs successful surgery on a member of the awilum class is paid 10 shekels of silver.

Btw, in the Middle Assyrian Laws, a physician comes into play if a woman crushes a man’s testicles in a brawl.

“And even if the physician should bandage it, but the second testicle becomes infected…” she faces severe punishment.

“And even if the physician should bandage it, but the second testicle becomes infected…” she faces severe punishment.

Dogs were part of life in ancient Mesopotamia, including as healers. 30+ dog burials were found below the ramp leading to the temple of the healing goddess in the ancient city of Isin, and the dog is the attribute animal of the healing goddess Gula

https://twitter.com/Moudhy/status/1165906648487079936?s=20

As our companions for tens of thousands of years, dogs do everything from helping to heal our wounds to guarding our homes to hunting with us.

In ancient Babylonia, they appear in proverbs copied down by students who were learning Sumerian in school 👇

In ancient Babylonia, they appear in proverbs copied down by students who were learning Sumerian in school 👇

https://twitter.com/Moudhy/status/1178739338726772737?s=20

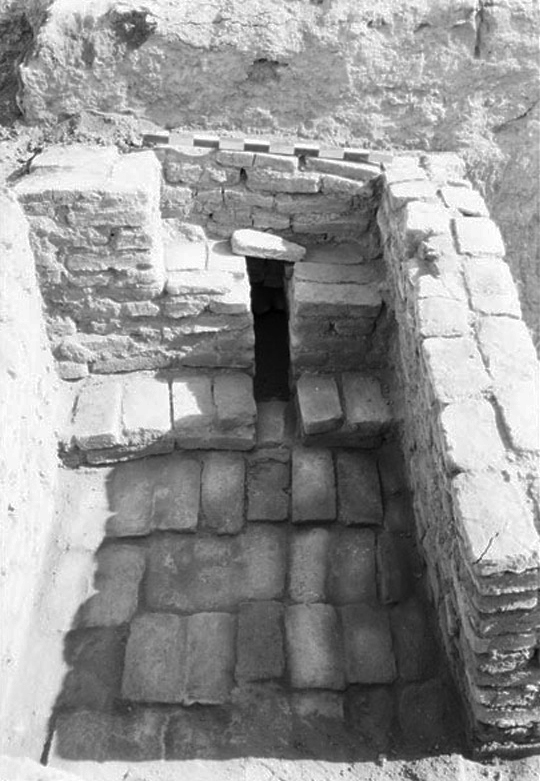

Because it’s part of everyday life — then as now — let’s not forget toilets in ancient Mesopotamia!

Here’s a great piece by @Augusta_McMahon on “Trash and Toilets in Mesopotamia”, complete with photos asor.org/anetoday/2016/…

Here’s a great piece by @Augusta_McMahon on “Trash and Toilets in Mesopotamia”, complete with photos asor.org/anetoday/2016/…

Finally, the Nuance Window.

If you’re interested in mental health and illness in ancient Mesopotamia, here is a very short piece I wrote for the brilliant @Papyrus_Stories which is a blog that showcases everyday stories from the ancient past papyrus-stories.com/2018/10/10/i-a…

If you’re interested in mental health and illness in ancient Mesopotamia, here is a very short piece I wrote for the brilliant @Papyrus_Stories which is a blog that showcases everyday stories from the ancient past papyrus-stories.com/2018/10/10/i-a…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh