In the past week, COVID cases have fallen in the majority of countries across the globe (see below for weekly change). But not all countries are locked down.

A thread on what might be - and what probably isn't - happening.

A thread on what might be - and what probably isn't - happening.

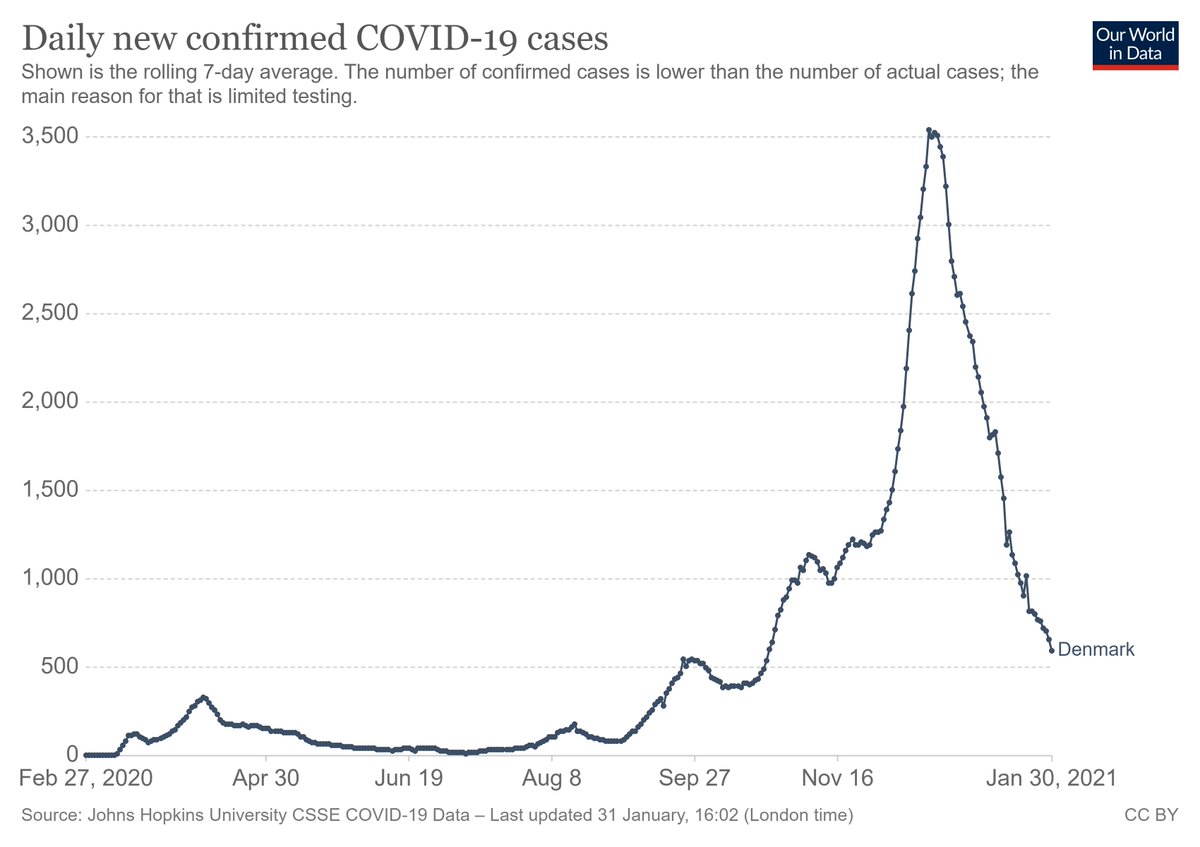

1. Lockdowns/restrictions have almost certainly had a major effect in countries that instituted them. Look at the peaked curves in the UK and South Africa - natural processes are generally smoother. But it's notable that current declines are even sharper than w the 1st lockdowns.

2. If this were just due to seasonality, one might expect similar behavior as with flu. But historically, flu rates in the US generally do not start to fall until March (see non-red lines below). Seasons likely contributed to the Oct rise, but likely not the Jan decline.

3. The slide above also shows that people have changed their behavior, substantially. Flu rates across the globe have been down. Human behavior is likely contributing to lower transmission rates than we would otherwise see (and may also have caused a rise over the holidays).

4. As a side note, we should stop invoking "low temps". In Europe, the lowest COVID mortality rates have been in Norway and Finland - compare to warmer Spain, or more-open Sweden. This is again about human behavior (crowding indoors, etc), not degrees C.

5. It's tempting to claim herd immunity. In Western countries w roughly similar age structures & good vital registration, SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence is roughly proportional to cumulative COVID mortality. In August, seroprevalence in the US was under 10%. bit.ly/3q9kp6Q

6. Since that time, cumulative COVID mortality in the US has roughly tripled. Meaning that a reasonable estimate of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in the US is now ~30%. Add in 12 vaccine doses per 100 people, subtract some waning immunity...maybe 35% of the population is immune.

7. Another observation is that cumulative COVID mortality per million is remarkably similar in most of Europe and much of the Americas. Meaning that in these places (which account for most confirmed COVID cases), ~30% population immunity is probably reasonable.

8. So, back to the original question - if we're seeing across-the-board declines in COVID cases, and it's not seasonal, not classical herd immunity, and not sufficiently high vaccination rates, what is it? (Other than lockdowns, which as above are definitely having an effect.)

9. I think the most logical explanation is one proposed initially by @mgmgomes1 and others - namely that we are seeing the effects of population immunity with heterogeneous mixing + strong behavioral effects.

10. Take a(n overly) simple example. Assume 60% of a population has zero respiratory contacts, while the other 40% lives life as normal. If 75% of that high-mixing group has immunity (e.g., 30% population seroprevalence), you could easily see herd effects.

11. It's worth noting that this ~30% level is very similar to what was proposed as a "herd immunity threshold" under these conditions. We just hadn't gotten there - until now.

(I'm leaving "herd immunity" in quotes, because it doesn't mean most people are immune - see below.)

(I'm leaving "herd immunity" in quotes, because it doesn't mean most people are immune - see below.)

12. If this is true, there are two important reminders.

First, what we are doing to limit viral spread is working - and must be continued (to some extent) in the short term. If we were to rapidly go back to "life as normal", we would see yet another wave of spread.

First, what we are doing to limit viral spread is working - and must be continued (to some extent) in the short term. If we were to rapidly go back to "life as normal", we would see yet another wave of spread.

13. Second, even though we may be seeing "herd" effects, it doesn't mean that most of the population is immune. People are still very susceptible to (dying from) this virus. Around the world, 13,000 people are dying every day - that's one confirmed death every 9 seconds.

In summary, I think the most logical explanation for falling COVID cases is: strong ongoing behavioral limitations + heterogeneous mixing + rising population immunity.

If true, there is reason for long-term optimism...but we can't let our guard down in the short term.

If true, there is reason for long-term optimism...but we can't let our guard down in the short term.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh