<THREAD>

A brief skirmish into the strange and curious world of Covid statistics, in part for therapeutic reasons.

Please bear with me. I may be some time.

A brief skirmish into the strange and curious world of Covid statistics, in part for therapeutic reasons.

Please bear with me. I may be some time.

So, where are we with Covid in the UK as things stand?

Well, hospital referrals on the basis of Covid-like-symptoms are now about as low as they’ve ever been since things kicked off...

Well, hospital referrals on the basis of Covid-like-symptoms are now about as low as they’ve ever been since things kicked off...

And, thanks to the sustained efforts of huge numbers of dedicated people, the groups which make up c. 90% of people who’ve (very sadly) died with Covid have now received their first dose of the Covid vaccine,

And yet, for the moment, we remain in ‘lockdown’,

and the stories of things to be concerned about continue to pile up.

Most recently, we’ve been told we still have ‘outbreaks’ in many areas of the country.

and the stories of things to be concerned about continue to pile up.

Most recently, we’ve been told we still have ‘outbreaks’ in many areas of the country.

But such claims about ‘outbreaks’ strike me as very strange.

Midway through a one-size-fits-all nationwide lockdown, how and why would you get transmission rates high enough to cause what can be classed as ‘outbreaks’ in 25% of the country...

Midway through a one-size-fits-all nationwide lockdown, how and why would you get transmission rates high enough to cause what can be classed as ‘outbreaks’ in 25% of the country...

...and yet low enough in the rest of the country for the overall transmission rate to be at an all-time low?

A couple of hypotheses proffer themselves.

A couple of hypotheses proffer themselves.

Hypothesis #1:

The parallel decline of Covid cases (see below) in locked-down countries like the UK and in Europe’s ‘control’ country (Sweden) is a coincidence; the current lockdown is what’s reduced cases in the UK; it’s just hit a bump in the road (for some unknown reason).

The parallel decline of Covid cases (see below) in locked-down countries like the UK and in Europe’s ‘control’ country (Sweden) is a coincidence; the current lockdown is what’s reduced cases in the UK; it’s just hit a bump in the road (for some unknown reason).

Hypothesis #2: At a national level, our number of cases is roughly what we’d expect given our tests’ false positive rates (FPRs), and the ‘outbreaks’ in a quarter of the country are noise,

which is what @deeksj’s estimate of the FPR suggests.

which is what @deeksj’s estimate of the FPR suggests.

But, before we dive into the details of FPRs and the like, let’s step back for a moment and ask a more fundamental question.

What exactly is ‘lockdown’?

Well, lockdown is a brave new experiment: the quarantine of millions of apparently healthy, asymptomatic people.

What exactly is ‘lockdown’?

Well, lockdown is a brave new experiment: the quarantine of millions of apparently healthy, asymptomatic people.

Until about a year ago, such an experiment would have been viewed askance.

For one thing, it was assumed liberal democracies wouldn’t sanction it.

For one thing, it was assumed liberal democracies wouldn’t sanction it.

And, for another, attempts to curb the transmission of a virus among a population’s less vulnerable individuals were known to be able to have counterintuitive effects;

specifically, they were known to be able to cause a population’s vulnerable individuals to bear *more* of a burden (rather than less of one).

Or at least they were until about a year ago.

But, as Professor Neil Ferguson has explained, China changed all that.

But, as Professor Neil Ferguson has explained, China changed all that.

On the basis of data published by a country known to have misinformed the world about Covid (and to have grossly violated the human rights of hundreds of thousands of its Muslim citizens in recent years), the rest of the world thought they’d give lockdowns a go.

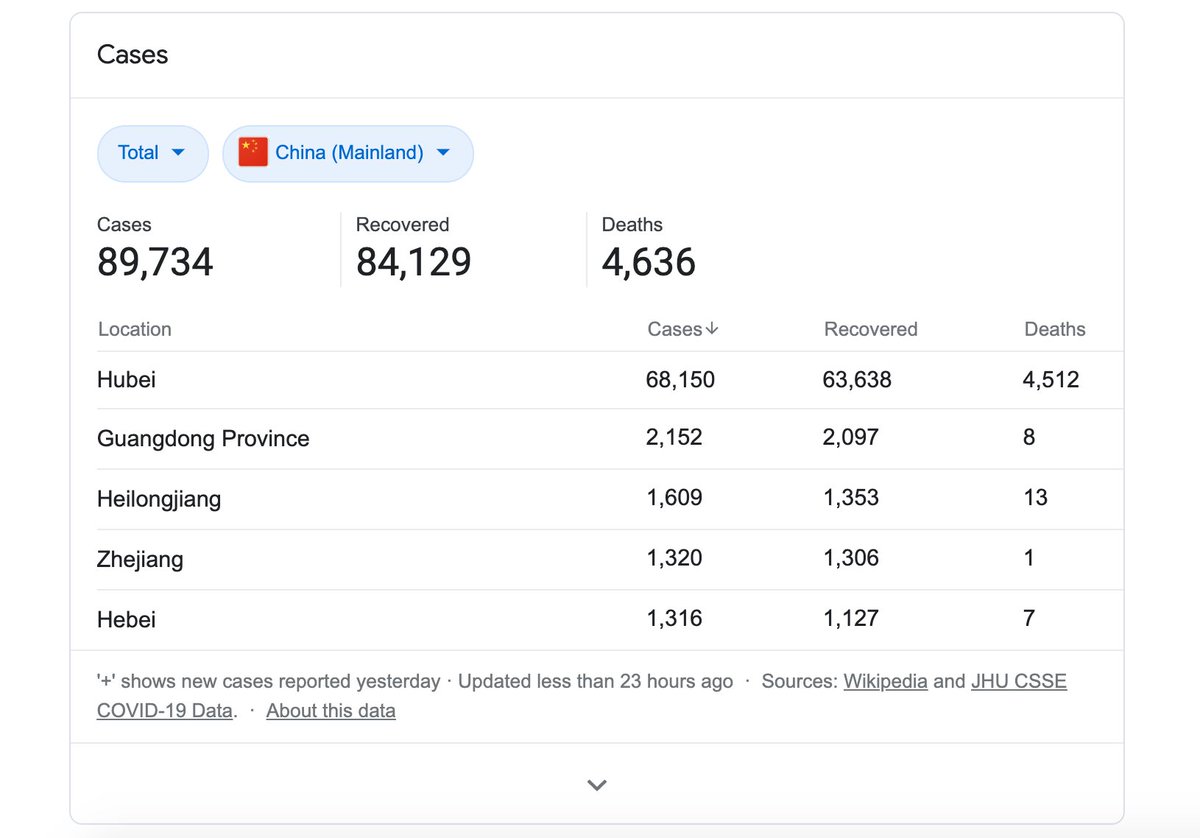

Note: Sadly, Ferguson abandoned his initial suspicions about the authenticity of China’s data. To date, China has reported a total of less than 5,000 Covid-related deaths out of a population of 1,400,000,000.

We thus passed legislation which means, if a lonely lady invites her neighbour into her house (or back garden) for a chat, or sits down on a park bench with her him/her, she’s committed a crime.

She hasn’t merely done something thought to be risky by certain people,

She hasn’t merely done something thought to be risky by certain people,

nor has she simply chosen to go against official government guidance;

she has committed a *criminal* *offence*,

which is true regardless of her desire/need for human interaction,

regardless of whether she’s been vaccinated,

she has committed a *criminal* *offence*,

which is true regardless of her desire/need for human interaction,

regardless of whether she’s been vaccinated,

regardless of whether ‘cases’ in her area are on their way up or down,

etc., etc.,

and which will remain true until our government decides otherwise.

etc., etc.,

and which will remain true until our government decides otherwise.

So, how will our government’s leaders make their decision?

Well, they say, of course, they’ll be led by the data (though SAGE insist all decisions are ultimately ‘political’),

which sounds well and good.

Well, they say, of course, they’ll be led by the data (though SAGE insist all decisions are ultimately ‘political’),

which sounds well and good.

But the particular way in which they say they’ll be led by the data is at best unclear,

since, as the risks associated with Covid decline, the government’s plan seems to be to test more and more people,

more and more of whom will be non-Covid-carriers and/or asymptomatic.

since, as the risks associated with Covid decline, the government’s plan seems to be to test more and more people,

more and more of whom will be non-Covid-carriers and/or asymptomatic.

At the time the government’s roadmap was unveiled, we tested about 500,000 people per day,

which generated about 10,000 positives (2%).

So: how low does our number of positives need to get until we lift lockdown entirely and put an end to the damage lockdowns do,...

which generated about 10,000 positives (2%).

So: how low does our number of positives need to get until we lift lockdown entirely and put an end to the damage lockdowns do,...

...included in which are the 50,000 cancer diagnoses thought to have been missed as a result of lockdowns?

The answer is, We don’t know, since the government hasn’t set an official target.

The answer is, We don’t know, since the government hasn’t set an official target.

Last week, it was suggested 1,000 might be a reasonable number--i.e., 0.2% of the number of people we currently test--,

which is a major concern,

since 0.2% is significantly less than every estimate of the FPR I’m aware of,

which means, if you tested 500,000 people who were known for a fact *not* to have Covid, you’d end up with a lot more than 1,000 positives.

since 0.2% is significantly less than every estimate of the FPR I’m aware of,

which means, if you tested 500,000 people who were known for a fact *not* to have Covid, you’d end up with a lot more than 1,000 positives.

That we can ‘test our way out of lockdown’ is, therefore, quite a scary prospect.

Our test regime could easily be precisely what *keeps* us in lockdown,

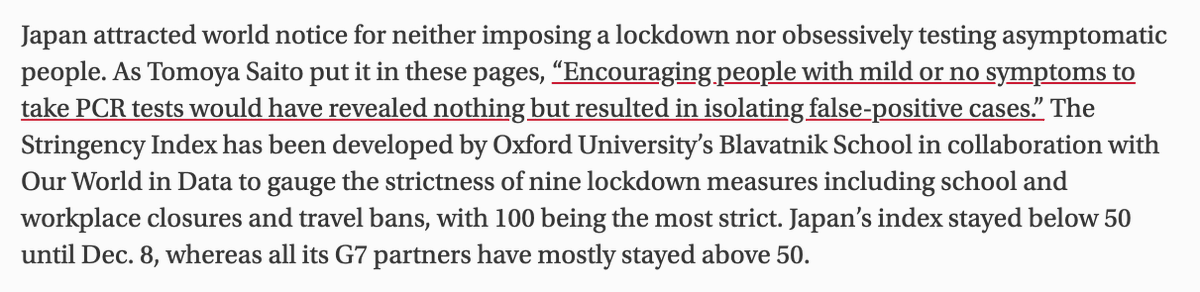

which is why Japan decided it was pointless to test asymptomatic people from the get-go.

Our test regime could easily be precisely what *keeps* us in lockdown,

which is why Japan decided it was pointless to test asymptomatic people from the get-go.

There’s then the question of how *many* tests we should do.

Is 500,000 tests per day too many or too few? (We’re now on more like 700,000 per day.)

Is 500,000 tests per day too many or too few? (We’re now on more like 700,000 per day.)

The leaders of our government seem to think the more tests they can do, the better. (Some people seem to want to do *millions* per day.)

But of course more tests *aren’t* always better.

But of course more tests *aren’t* always better.

Before you set out to test hundreds of thousands of asymptomatic people, you need to make sure those tests will do more good than harm. (You might also want to consider what else you could accomplish with a few billion pounds.)

We could routinely screen the whole population for all sorts of types of cancer, but we don’t.

Why? Because we know it would do more harm than good in many instances.

Why? Because we know it would do more harm than good in many instances.

Take our current plans/ambitions to test all school children.

At present, our population of school children isn’t far off 10 million.

Suppose we test all of them every day.

At present, our population of school children isn’t far off 10 million.

Suppose we test all of them every day.

Given an FPR of 0.32%, that will result in the unnecessary exclusion of c. 32,000 children each day (who’ll have to isolate for at least a week),

together with the unnecessary isolation of whoever’s in those children’s bubbles/households.

together with the unnecessary isolation of whoever’s in those children’s bubbles/households.

So, by the end of an average week, we could easily end up with, say, 500,000 people in isolation for no reason at all (at no small cost to them or to society at large),

which isn’t exactly a great outcome.

So, what’s the upside?

Well, we could reduce transmission.

which isn’t exactly a great outcome.

So, what’s the upside?

Well, we could reduce transmission.

Or so it’s claimed.

But between who?

We don’t need daily tests to reduce transmission from children who are *symptomatic*; we just need to convince their parents to keep them at home.

But between who?

We don’t need daily tests to reduce transmission from children who are *symptomatic*; we just need to convince their parents to keep them at home.

And transmission from ‘asymptomatic Covid-carriers’ is pretty much unheard of.

conservativewoman.co.uk/covid-the-woef…

conservativewoman.co.uk/covid-the-woef…

So all we can really hope to achieve by means of daily tests is to reduce transmission from *pre-symptomatic* children,

which, when it’s been studied, has been found to make up a pretty small proportion of the total transmission (about 6%) (though more study is needed).

which, when it’s been studied, has been found to make up a pretty small proportion of the total transmission (about 6%) (though more study is needed).

We desperately, therefore, need to have serious conversations about our government’s proposed test regime.

Yet such conversations have become progressively more difficult to have over recent months.

Yet such conversations have become progressively more difficult to have over recent months.

Companies like Twitter, YouTube, and Facebook have become progressively more hostile to ‘skeptics’, i.e., to people who want to subject their governments’ policies to critical scrutiny, which has typically been done by ‘the opposition’.

And, rather than engage with the claims of pathologists such as @ClareCraigPath, MPs now simply brand them as ‘dangerous’.

In other words, we’ve begun to lock down not only people but conversations.

So, what can be done?

Pray.

Contact your MP.

Write to your childrens’ schools and tell them about your concerns.

So, what can be done?

Pray.

Contact your MP.

Write to your childrens’ schools and tell them about your concerns.

Listen to a wide range of people on Covid-related issues.

Retweet the present thread.

Inform other people about your concerns (in a calm way).

And sign the petition below.

petition.parliament.uk/petitions/5754…

Retweet the present thread.

Inform other people about your concerns (in a calm way).

And sign the petition below.

petition.parliament.uk/petitions/5754…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh