#NowWatching “Batman v. Superman.”

Which is a film I’ve always admired in its complete and unequivocal commitment to what it’s doing.

Which is a film I’ve always admired in its complete and unequivocal commitment to what it’s doing.

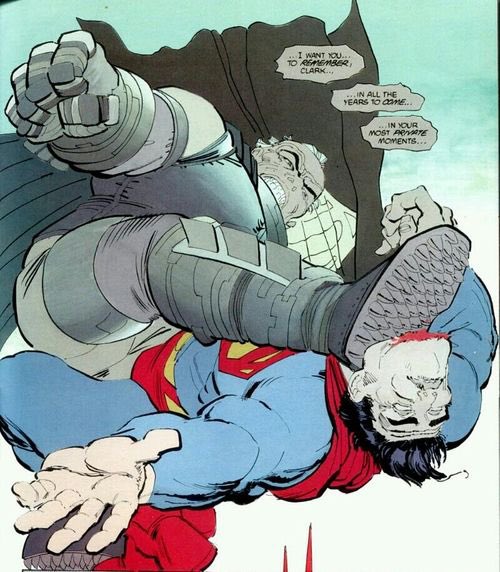

As with a lot of Snyder’s films, “Batman v. Superman” is surprisingly nuanced in its study of fragile and dangerous masculinity.

Notably, in Snyder’s movies, whenever men try to solve anything, it inevitably gets bloodier and messier than it needs to be.

Notably, in Snyder’s movies, whenever men try to solve anything, it inevitably gets bloodier and messier than it needs to be.

Thomas Wayne gets a single line in “Batman v. Superman”, but consider how much Snyder tells us about Thomas and what happened.

A mugger tried to rob the Waynes. Instead of surrendering his money and valuables, Thomas stands his ground. He acts “like a man.”

A mugger tried to rob the Waynes. Instead of surrendering his money and valuables, Thomas stands his ground. He acts “like a man.”

I can’t find a gif, but think about this shot. Thomas pushes Bruce back to protect him, but his hand then tightens into a fist.

Snyder shows us this, Thomas deciding to fight his ground. He also shows us Bruce watching this, learning from it.

Snyder shows us this, Thomas deciding to fight his ground. He also shows us Bruce watching this, learning from it.

One of the big recurring motifs in “Batman v. Superman” is that Bruce learned what it meant “to be a man” from his father Thomas.

After Thomas’ macho pride gets Martha & himself killed. It’s almost as if fetishising strongmen who position themselves as tough guys is a bad idea.

After Thomas’ macho pride gets Martha & himself killed. It’s almost as if fetishising strongmen who position themselves as tough guys is a bad idea.

This is interesting, as the Batman mythos tends to focus on Thomas and Bruce, often ignoring or overlooking the importance of Martha.

Interestingly, David Brothers has singled out Frank Miller, a key influence on “Batman v. Superman” as an exception.

comicsalliance.com/frank-miller-b…

Interestingly, David Brothers has singled out Frank Miller, a key influence on “Batman v. Superman” as an exception.

comicsalliance.com/frank-miller-b…

It’s notable that this theme of warped and grotesque masculinity - machismo metastaticising into something monstrous - runs through “Batman v. Superman.”

Consider the big fight, charged with masculine signifiers; the Turkish bath, the urinal, the giant pulsing spear.

Consider the big fight, charged with masculine signifiers; the Turkish bath, the urinal, the giant pulsing spear.

And what is Doomsday in “Batman v. Superman” but a literal stew of toxic masculinity?

It’s a Frankenstein’s monster, a non-feminine birth of Luthor’s tech-bro hubris and General Zod’s “blood purity” Krypto-Fascism.

It’s a Frankenstein’s monster, a non-feminine birth of Luthor’s tech-bro hubris and General Zod’s “blood purity” Krypto-Fascism.

Interestingly, the movie’s dialogue is always very gendered on this point. It’s “men of power” who “obey neither power nor principle”, it’s “good men” who are turned “cruel” by “powerlessness” and impotence.

It’s never “people”, never “humans.” It’s men. Very specifically men.

It’s never “people”, never “humans.” It’s men. Very specifically men.

Incidentally, it’s white men as well.

“Batman v. Superman” is surprisingly interested in the kinds of marginalisation rarely depicted in superhero films.

The neighbourhoods over-policed by Batman, the kitchen staff with relatives across the border.

“Batman v. Superman” is surprisingly interested in the kinds of marginalisation rarely depicted in superhero films.

The neighbourhoods over-policed by Batman, the kitchen staff with relatives across the border.

Notably, as its male characters spiral out of control, “Batman v. Superman” makes the point to have its female characters act as voices of reason.

This is notable early on, with even June Finch standing up to Lex Luther and trying to hold fair hearings on Superman.

This is notable early on, with even June Finch standing up to Lex Luther and trying to hold fair hearings on Superman.

I know fans hate the bit where Luther lashes back at the powerful woman who chastised him by sending her a jar of urine.

But it’s meant to be creepy and pathetic; a petty manchild trying to mark his territory. But have you seen how insecure men react to women who call them out?

But it’s meant to be creepy and pathetic; a petty manchild trying to mark his territory. But have you seen how insecure men react to women who call them out?

It’s very much a direct invocation of that sort of tribal and animalist nonsense that you see a lot of insecure men evoking.

It’s that “alpha” or “wolfpack” dominance thing played out in the saddest and most pathetic way imaginable.

It’s that “alpha” or “wolfpack” dominance thing played out in the saddest and most pathetic way imaginable.

(An aside here to note that Luther essentially radicalises Wally, the suicide bomber, by appealing to his masculinity.

Wally’s motivation to confront Superman is that Superman made him “half a man”, and that his wife left him. Again, that idea of masculine insecurity.

Wally’s motivation to confront Superman is that Superman made him “half a man”, and that his wife left him. Again, that idea of masculine insecurity.

The movie also has a recurring fascination with the football rivalry between Gotham and Metropolis, fixating on how violent and aggressive that rivalry is.

It’s a constant reminder of how deep, deeply silly and juvenile the idea of Batman and Superman fighting is.)

It’s a constant reminder of how deep, deeply silly and juvenile the idea of Batman and Superman fighting is.)

Incidentally and deliberately, at the climax, it’s the female characters who stop the self-destructive madness of the movie’s three (or four) male leads; Lois, Wonder Woman and (yes) Martha.

The Knightmare Scene is interesting give what we now know about Snyder’s original plans for Bruce, Clark and Lois.

Indeed, rewatching “Batman v. Superman”, it’s impossible not to see the set-up for the idea of a Bruce and Lois romance.

Indeed, rewatching “Batman v. Superman”, it’s impossible not to see the set-up for the idea of a Bruce and Lois romance.

The plan was that Bruce and Lois would bond in Clark’s absence, they would hook up, Lois would get pregnant, Bruce would die and Clark and aloud would raise the son.

Superman fans got weirdly and intensely insecure about this, playing into bizarre right-wing fantasies.

Superman fans got weirdly and intensely insecure about this, playing into bizarre right-wing fantasies.

Fans seemed to read this as (and I can’t believe I’m typing this, but it’s the internet) Bruce effectively “cucking” Clark. To which: ew.

It’s not a very flattering look for Superman fans to immediately read that idea that way. It’s also weirdly territorial about Lois.

It’s not a very flattering look for Superman fans to immediately read that idea that way. It’s also weirdly territorial about Lois.

As somebody whose family includes adopted children and half-siblings, that argument over the idea of Clark raising Bruce’s son *really* rubbed me the wrong way.

(Also worth noting that Snyder has several adopted children. So be honest about where the story’s heart would be.)

(Also worth noting that Snyder has several adopted children. So be honest about where the story’s heart would be.)

What’s really interesting about the internet’s reaction to this is what it says about fragile views of masculinity in the modern age.

Superman was raised by a man who was not his biological father. It would make him no less a man to raise a child not his biological offspring.

Superman was raised by a man who was not his biological father. It would make him no less a man to raise a child not his biological offspring.

In this context, the Knightmare sequence plays as its own interrogation of masculinity.

It’s a dark future, but one defined by Superman’s embrace of this toxic masculine nonsense. It’s a future where he thinks of a Lois as belonging to him, and something taken from him.

It’s a dark future, but one defined by Superman’s embrace of this toxic masculine nonsense. It’s a future where he thinks of a Lois as belonging to him, and something taken from him.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh