On nature, prophets, the deep past, & national history writing. It is regretful that Matia Kigaanira Ssewannyana Kibuuka has been ignored in much of Uganda’s national history writing. He is one of the most consequential activists of the 1950s, but he is rarely discussed. 1/17

Matia Kigaanira (MK) was born in the mid-1930s. He became a driver for the Trans-Congo/Uganda Company. At the age of 17, while in a restaurant in Fort Portal, the lubaale Kibuuka rested on Kigaanira’s head. Overcome with Kibuuka’s power, 2/17

MK smashed his plate onto the floor & announced his imminent return to Mbaale, where Kibuuka's principal shrine was located. MK’s transformation into the prophet Kibuuka was spectacular. First, MK was a Museenene. But Kibuuka’s shrine in Mbaale was kept by Ndiga elders. 3/17

When MK appeared at Mbaale in 1953, Ndiga elders were sceptical. But to validate his newfound role, MK climbed the tree where Kibuuka’s body had plummeted 200 yrs earlier by Nyoro arrows. Kabaka Muteesa II had just been forced into exile by Governor Cohen. 4/17

And Buganda needed its god of war to speak words of power. Once on top of the tree, MK Kibuuka foretold Muteesa II’s return. The Ndiga elders were deeply moved and persuaded. They extended honorary status into their clan in order to complete the anointment of a new prophet. 5/17

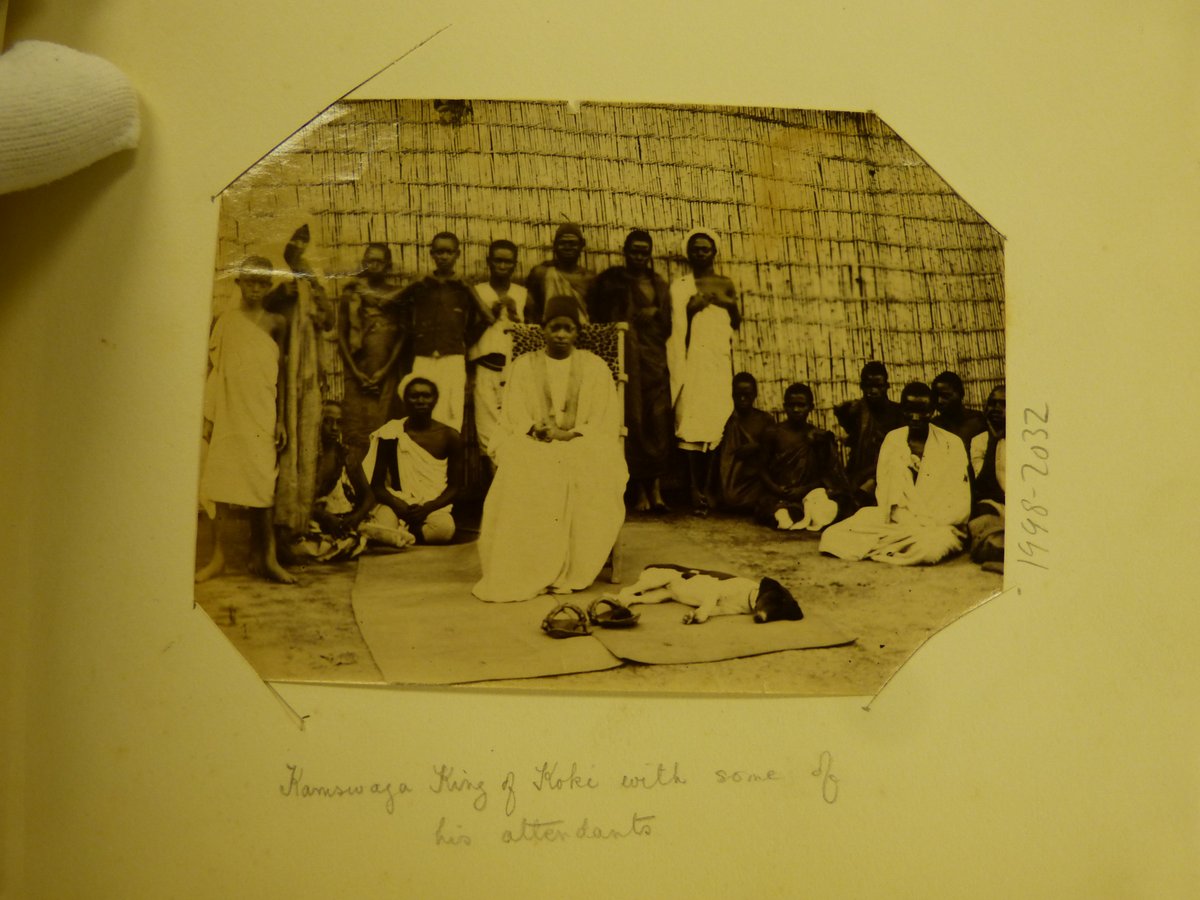

With the elders’ blessings, Kibuuka travelled to Mutundwe (pictured here). At Mutundwe, the prophet claimed to communicate with Kabaka Muteesa through the wind. He admonished Ugandans to stop paying taxes and to stop attending churches & mosques. 6/17

The Uganda Nationalist Party Movement openly supported the prophet, and they called on everyone to build lubaale shrines near their homes, openly challenging the colonial government’s Witchcraft Ordinances. 7/17

Kigannira healed the sick and prophesied with a snake around his neck, drawing attention to his command over the histories of Bemba Omusota. MK worked with animals, trees and rocks to signify moral order in a state torn asunder by colonial capital and the Kabaka’s exile. 8/17

During one demonstration near Mutundwe, a colonial officer was killed. MK was sentenced to life in prison. But after 3 months, he escaped and relocated to Kkungu rock, seen here. According to MK, a crested crane flew into the prison. MK then boarded its back and flew away. 9/17

Once at Kkungu, a 2-headed snake transported food & money to the top of the rock. The prophet had the power to overcome the concrete boundaries of colonial prisons, while also having the power to elevate to the rock’s summit. Of course, the crested crane had deep meaning. 10/17

It was associated with the Ente and Ngaali clans. It also symbolized public healing. As one proverb noted, “Eyeemanyi amalwalira: tatega ngaali.” By WWI, the crane had also been co-opted by colonial officials into Uganda’s flag. But in 1950s Uganda, 11/17

the national bird flew at the discretion of the prophet, not colonial ceremony. By soaring with Uganda’s crested crane, Kigaanira postured himself as a different sort of national exemplar. MK attracted much attention, including from members of the Namirembe Conference, 12/17

who were then working to secure Muteesa’s return. The Conference also laid the groundwork for UG’s Independence timeline. After Dr. Ernest B. Kalibala (a committee member) visited Kibuuka, the Conference passed a resolution forbidding others from seeing the prophet. 13/17

When Kabaka Muteesa finally returned from exile in 1955, there were far-reaching discussions about who was actually responsible for securing his return: the elites of Namirembe or Kibuuka, who was now being talked about throughout Uganda & the colonial office in London. 14/17

It was not a coincidence that Abu Mayanja worked to secure the relics of the historic Kibuuka, which had been shipped overseas by Apolo Kaggwa in the early 1900s. Mayanja now hoped that the returned relics would be among the first objects to fill the Uganda Museum. 15/17

Late colonial nationalism in Uganda was not simply an elitist affair: it drew from older ideas about healing, prophets, & a natural world permeated w/ political power. Kibuuka's power & prophecy commanded the attention of UG's foremost nationalists & colonial officials. 16/17

***All images taken and used with permission. This thread draws from the following article, where Kibuuka is explored is much greater detail: bit.ly/3rWWbgG 17/17

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh